Last summer my thoughtfully considered — although some spousal units might say juvenile — urge to buy another motorcycle evolved into a mature decision to seek out and purchase a vintage bike. [Author’s Spousal Unit: “Mature? Hah!”]

Anyway, my desire to acquire an Airhead (as the pre-1994 BMW boxers are affectionately known) became irresistible.

I wanted vintage, but not too vintage, if you know what I mean. A BMW /5 is the first Beemer generation to have 12-volt electricals, an oil filter system, and electric start. At the same time, it is the last generation to have a practical kick starter and the charming headlight bucket that goes back decades. The 750 cc version is adequate for modern legal speeds anywhere in the country. So, an R75/5 became the ticket I needed to punch.

The search started and I began to discover the support offered by the vintage Airhead community. Forum members answered my newbie questions. One volunteered to inspect on my behalf a bike that was a state away from my home in Gig Harbor, Washington. Then, a likely bike appeared on Denver craigslist.

A 1973 R75/5, short wheelbase. Grey, with the “toaster” tank. Wixom fairing, newer tires, extras, 43,000 miles, good to excellent condition. The seller had owned it for 25 years but could no longer ride. He sent many pictures, we talked and we agreed on a price, subject to my inspection. I flew from Seattle to Denver, hoping to make the purchase and ride it home.

The bike was just what the seller had represented it to be. From 10 paces, The Toaster looked pristine, but closer inspection revealed the inevitable flaws of an original, 43-year-old, 43,000-mile bike. The front fender was chipped and the tank had paint bubbles. The tach didn’t work and the clutch and brake cables were stiff. Oil spots on the otherwise clean garage floor showed where the bike had marked its territory.

All this had been clearly conveyed to me by the seller, so I threw my leg over the /5 for my first Airhead ride. She fired right up into a smooth idle and I carefully backed down the driveway while noting the expected, nearly nonexistent effectiveness of the double drum front brake in reverse. A few throttle blips demonstrated the Boxer Twist as the bike tried to rotate around the engine. I eased out the clutch and felt the seat rise as the driveline took up. I was already grinning under my helmet as I took off.

After several laps of the neighborhood — waving to the seller each time I went by — I returned and we settled the transaction. He showed me everything he could about the bike, agreed to ship what extras I couldn’t carry with me, and told me a few stories from his 25 years with the machine. His riding days were over, and I could tell that it was hard for him to let it go.

I called my wife to let her know I was starting the 1,300-mile journey home, shook hands one last time, and rolled away pleased as punch with our new Toaster. Two hours later, the bike would be lying on its side, dumped, with oil pouring out into a spreading puddle.

The journey home

I left Denver northbound on I-25 with no more of a plan than to put down as many miles as I could before sunset or fatigue brought me to a halt. Once clear of traffic, I tested the brakes and handling at cruising speed, then settled in behind the fairing, another novelty for me. I held a smooth 70 mph on the GPS as the speedometer jumped around and the tach needle self-destructed into bits and pieces. All was well.

Miles of marvelous cruising later my left boot slipped off the peg. I put my foot back on and it slipped off again. Looking down, I saw that both peg and boot were covered in oil.

Crap.

A glance at the instruments showed no red lights, and I had verified the working of the low oil pressure light before I left. No smoke trailed behind, nor any James Bond-style pursuit-spoiling oil slick. My phone’s navigation showed the next exit to be just two miles ahead, and it had a filling station. I pressed on, pulled up to the pumps, set the bike on the center stand, and shut down.

A call to Matt, an Airhead guru in Portland, Oregon, was definitely in order. Deep in thought, hoping he would pick up, I dialed Matt’s number and stepped back, phone to my ear, to lean my butt against the seat of The Toaster. Crash!

I jumped to the side, staggering. In my reverie, I had tried to lean by habit against the seat of a side stand motorcycle, but the BMW stood on its center stand, the first I’ve ever owned. I had knocked it right over, and oil glugged from the capless transmission case.

I wrestled the bike up as quickly as I could, placed it on the sidestand, saw that oil still poured out due to the lean angle, put the bike onto the center stand, then walked away to sling curses into the Wyoming wind.

Somewhat calmer, but still astounded at my own stupidity, I assessed the damage. The formerly pristine right mirror, bar end, and muffler were now scratched. The bike had gone unscathed for 43 years, and I managed to goober it up in my first two hours of ownership. Maybe cussing more would help.

Venting complete, I re-dialed Matt, he picked up, and he conveyed practical words of wisdom to my overwrought brain. The bike would take readily available gear oil, no problem. The gear box isn’t pressurized, so if I could cap the filler hole somehow, it should stay full. Given that the case was still at least half full, I could ride it a short distance without damage.

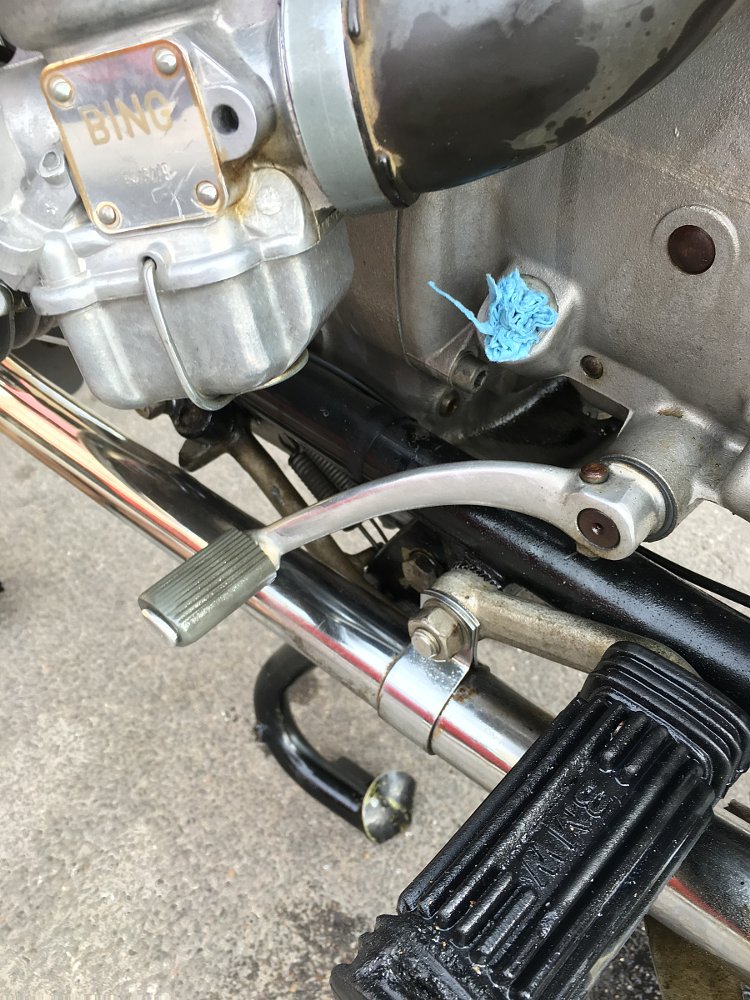

I managed to fill the bike with gas without any more disasters and found an auto parts store a short distance away, getting to it 15 minutes before it closed until Monday morning. I bought gear oil, a funnel, and a roll of blue shop towels. Outside in the parking lot, I filled the transmission case, then cut and rolled sections of shop towels into the hole, tamping them as tightly as I could. That would have to do.

The /5 purred happily along, however, even as I watched the paper towel wad darken with soaking oil. It was a relief to take a freeway exit at dusk. I checked into a motel, ate dinner, then walked across a big parking lot to a Wal-Mart.

Once again, we settled down to a cruising speed of 70-75 mph, and I found it to be strangely relaxing to stay mostly in the slow lane, only occasionally passing other traffic. This rider is usually in the fast lane, and usually traveling at pace that requires keeping a sharp lookout for The Man. Now, without the worry of what might be lurking over hills or around corners, I found that I had lot more time to enjoy the views.

Grassland prairie turned to badlands with the only green being the occasional circles of pivot agriculture. Dry ranches sported scattered herds of cattle and fleeting bands of pronghorn antelope. I played PassMePassYou with 18-wheelers as the truckers let their heavily loaded rigs roll out on the downgrades and dropped through their gears on the upslopes. The Toaster cruised, asking only for a fuel stop every two hours, and I gained enough confidence in her manners to take a few pictures from the saddle at speed.

The only troubles on this long, mile-eating day was once when the Toaster sputtered to let me know that I needed to switch to reserve now, and to remember to do it on both sides of the bike as well, once for each carb. The other was that the bike took it into her head to honk her own horn whenever the mood struck. Fiddle as I might with the button, she beeped whenever she felt like it and stopped beeping based, so far as I could tell, on whimsy. That wouldn’t be the last I’d hear of the horn.

We rolled into Ontario, Oregon after approximately 600 miles, sore, tired, and pleased with the long day. I parked the bike where the motel desk clerk could see her, ate what I felt was a well deserved dinner, and went lights out only one state from home.

Airhead in the home stretch

Up the next morning with the sunrise, the table leg cap was still glued in place, engine oil level fine, and tire pressures good, so we fired up and headed north on yet more slab, I-84. Approaching the Columbia River, I faced a westbound choice of more flat, efficient, divided-lane highway through the Gorge on the Oregon side of the river, or taking the two-lane Washington 14 on the north side.

The choice was obvious — Washington 14 through the Columbia Gorge is one of those roads for which God made motorcycles and I’d been looking forward to it since the start of the trip. I crossed the big river on I-82’s Umatilla Bridge and immediately encountered a well known Washington feature — rain.

Sigh. It doesn’t rain much on the dry eastern half of the state, but I guess I was being welcomed home. After a stop to don rain gear, I pressed west on 14 through moderate to heavy showers while being very cautions on the glorious sweepers through the sage brush, because these roads don’t get sluiced off very often. The rain lasted for only 60 miles, and I was able to pull off at an overlook of the John Day Dam on the Columbia to remove and stow the rain gear for the rest of the trip.

With sunny skies, dry roads, and a happy, now-familiar bike underneath me, we really began to enjoy Highway 14. With its big sweepers, tight twists, hill climbs to magnificent views followed by descents to pavement at river’s edge, riding the Columbia Gorge on the Washington side should be on every motorcyclist’s bucket list.

The self-blowing horn

The bike had behaved since late the day before, but now she turned puckish. We passed a young woman unloading groceries from a car in her driveway and I freely admit that I was admiring her, um, technique, but I was not the one who beeped the horn as we whizzed by. The same thing happened several times with women, including once with multiple toots when stopped at a crosswalk and three young lovelies crossed, with me turning red behind my sun visor. As it turns out, The Toaster has a sense of humor, with a bit of a mean streak.

She can also be impatient. We came up behind a Jeep Wrangler in the middle of a particularly glorious set of scenic curves. It didn't really bother me to get slowed down, but the bike obviously had a different opinion because she beeped at the Jeep. Beeped again. I saw the driver’s head snap a glance into his mirror at the butthead behind him. The Toaster beeped again, again, and again, and I fiddled with the button until I realized that it looked like I was intentionally pressing it. I raised my left hand into the air to show the driver, who was by now watching me closely, to show that it wasn’t my fault, but that made me worry he’d think I was flipping him off.

The bike honked again and, to my surprise, the Jeep pulled over to let us by. I waved a thank you, got a wave in return, and heard The Toaster chuckle to herself as we accelerated into the next curve. And you know what? Once we left the Gorge and got back on the slab, where there were no more pretty girls to see or slowpokes to nudge out of the way, the bike didn’t beep again.

The final leg of the journey was slab north up I-5, and we finally pulled into the driveway to get a hug and kiss from my wife and park The Toaster in the garage to get acquainted with her new stablemates. After 1,300 miles, an inauspicious start, an en route repair, and the discovery that the bike has a personality of her own, we were home.

Postscript

As planned, I relieved The Toaster of her big fairing and, of course, the bike got lighter and better handling. She cleaned up well from the long trip and my wife, who rides also, loves her too. As this is being written she’s torn down in the garage getting a complete refresh, including rear shocks, front end rebuild, instrument cluster rebuild, paint, etc., etc. The horn, which was mounted to the fairing, has not been remounted and may not be. I can’t really afford to get into that kind of trouble locally.

On the other hand, she really wouldn’t be herself, The Toaster, without her horn, would she?