Ah, torque, my favorite byproduct of burnt hydrocarbons.

But I like old-fashioned torque, too, produced manually. “Torque” is actually derived from an old French word meaning, “Reef on that-there breaker bar, Cletus!” Torque as it relates to fasteners is an important concept in both theory and practice. This article, in the alarmingly misinformed non-comprehensive style typical of the author’s usual writing, will likely be heavy on the latter and light on the former.

Why does proper torque on a fastener matter?

Threaded fasteners are relatively inexpensive, simple, inexpensive, and very easy to disassemble and reassemble. They’re also inexpensive, so that’s why you see them pretty much all over your motorcycle, regardless of marque.

Correct torque keeps items fastened together without compromising either the items or the fastener. Fasteners hold items together because they are elastic. As we tighten the fastener, their fight to return to their unladen state is what holds the items they fasten together. At some point, a fastener stops being elastic (wanting to return to its original state) and starts being the opposite, plastic (it just deforms).

Get outside the zone of elasticity, and you can compromise the strength of a conventional fastener. If you’re lucky, it will noticeably deform (pulled threads or a twisted bolt shank, or other visible damage), and you’ll replace it. If you’re not lucky, you may just have a fastener that passes a visual check, but is now far weaker and is not actually applying the correct clamping load upon the items to be fastened. In short, it ain’t doin’ its job.

Interestingly, that zone of elasticity (before failure occurs) is actually pretty large. And the clamping force of deformed fasteners stabilizes quite a bit relative to bolts in the elastic zone, so engineers began to incorporate this into some critical areas. A 2012 Kawasaki KX250, for instance, has one-time-use-only cylinder head bolts, often known as “TTY” or “torque-to-yield.” The bolts are designed to be used once, deform, and be discarded when disassembled. If you pull one out, they sometimes get “skinny” where they start to yield. It becomes pretty clear that reusing them would be a bad idea.

Proper torque is important. This was a dry answer, but understanding roughly how fasteners are (and can be) engineered to succeed — or fail — is important stuff.

What are some of the ways torque can be quantified?

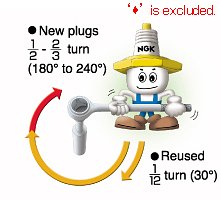

In the motorcycle realm, we usually see fastener torque specified in terms of inch-pounds or foot-pounds in the USA, but there are a few notable exceptions where angular torque is specified, too. NGK mentions angular torque often for their spark plugs. Harley-Davidson has used both on the same fastener: pre-torque to a given load, then tighten a set amount of degrees beyond that. (This method is pretty popular in the automotive world.)

What’s the best way for a DIYer to snug up fasteners accurately?

Why, with a torque wrench, of course! There are a few different styles one could pick up — clicker torque wrenches, beam-style torque wrenches, and electronic transducers are common at the consumer level. All have their advantages and disadvantages.

Clickers provide an audible and tactile indication you’ve hit your desired torque, but also require careful handling and periodic calibration.

Beam-style torque wrenches are easily checked for calibration by eye, but need to be used in a way where the scale is visible, which can make some torque procedures ungainly or impossible. (Anything downward facing becomes a yoga exercise if your torque wrench isn’t double-headed!) And if you are really putting your all into achieving a torque, sometimes the scale can be a bit herky-jerk if you tremble as you wrench!

Electronic transducers are nice to have and can be used on nearly any tool you already own, but add quite a bit of height to your ratchet stack, so it may not fit, especially if you’re using it on an item installed in or on the bike.

All have a place. The more tools you have, the more options you have.

How should I use my torque wrench?

Carefully. If you have a case for it, use it. They’re pretty delicate instruments. Please don’t use your torque wrench to really bear down on a stuck bolt. There’s a temptation to do that because it’s the longest breaker bar many people own, but you’re better off with a tool designed for such a thing.

Throwing a torque wrench out of whack may necessitate recalibration, or, at worst, a new tool. In fact, some wrenches only read in a clockwise direction, because that is how they are meant to be used. Rust, dirt, and galling can all cause a fastener to need a hell of a lot more “oomph” to loosen it than to reset it to spec.

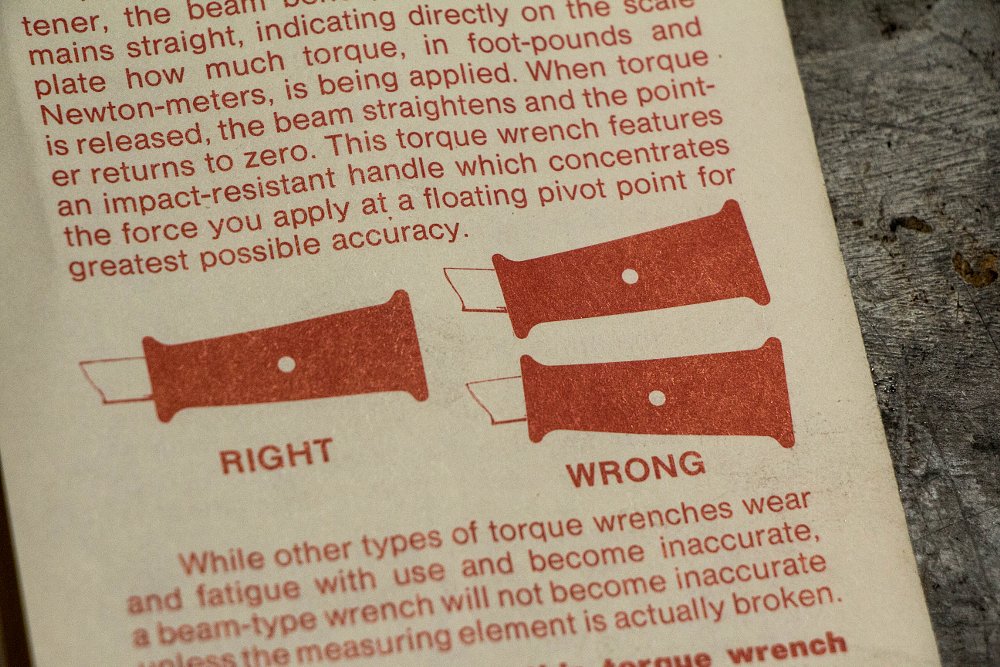

Also be mindful of how your wrench is to be handled. Use one hand, use no cheater pipes, applying torque slowly and smoothly — no wrenching and jerking. On some tools, the handle is often hung in the center on a pin. If you have one of these, they’re very accurate if used correctly — don’t allow either end of the handle to pivot against the tool body when taking your reading. If there's a knob or obvious cutouts for your fingers, use them! Doing something else makes the reading less acccurate.

If you have a clicker-type wrench, dial it back to zero before putting it away, or the spring within may take a “set,” making it a bit weaker and affecting the tool’s accuracy. (I’m actually repeating what everyone’s heard since the beginning of time, because this unloads the tension from the spring, which can take a “set.” I’ll propose an alternative argument: springs weaken from cycling, not from being loaded.)

Be aware that it’s possible to be overtight. If you are checking bolts for snugness, and one does not move but your wrench “clicks,” you may well be very overtight. Sometimes it can pay to back one off and re-check the torque, just to be sure. You also want to check the torque on a bolt that’s moving. If a fastener hasn’t budged in a bit, sometimes chemical reactions can cause the threads to “lock” to one another. Friend and mechanical engineer Evan Aamodt summed things up: “Avoid cranking on a bolt that's not moving relatively freely. Sticky hardware can be a sign that your threads aren’t engaging correctly, or that there’s something obstructing the movement of the fastener.” Basic advice, but still very good.

You should know the rules about extensions and crow’s feet (torque adapters.) Extensions do not appreciably affect torque values. Torque adapters do not appreciably affect torque when placed perfectly perpendicular to the body of the tool. If placed in-line with the tool to assist with reach, there are calculators and apps that can be used to recalculate the reduced specification to use on the scale to achieve the desired final torque, as that position will increase your mechanical leverage and readings at the gauge will be incorrect as read.

And it might sound very basic, but make sure you’re reading the spec correctly. I have done plenty of thread repair for those who misread a torque spec. Newton-meters to foot-pounds is bad enough, but inch-pounds being mistaken for foot-pounds almost always causes damage to a fastener or an item being fastened. (Or, more usually, both.) We’ll come back to this thought in just a moment — it comes into play in another question I’ll answer in a bit here.

Do I lubricate the fastener threads?

Maybe. What’s the spec call for? Much of the resistance in a threaded fastener is in the friction between the threads and between the head of the fastener and the fastened item. Lubricating these areas with oil, never-seize, or even threadlocker or pipe dope (in the case of tapered threads) can drastically reduce that fraction, changing the torque appreciably. If no detail is given, bolts and screws are assumed to be clean, rust-free, and dry. Taking a wire brush to an older fastener is often prudent. Even plating can affect torque, so if you’re replacing a bolt with a dress-up item, recognize torque readings will likely be affected.

There are times when specs will call for pre-oiled or pre-treated fasteners. In this scenario, like many others in the motorcycle realm, readers are leaders. If you elect to add a thread-locking agent or anti-seize compound, the manufacturer will often instruct you on how to calculate the correct torque specification.

If lubricating threads, you’re walking a line between potentially overtorquing and avoiding thread galling, which is when pressure and friction between threads actually cold-weld themselves together. Particularly susceptible to galling are stainless and aluminum items, because they form a thin oxide layer that makes it particularly easy for fasteners to bind up. Also, look out for poorly formed threads and very fine threads; they can be susceptible to thread galling, as well. If you can’t thread the nut and bolt together by hand, you are at risk for thread galling. And don’t use fasteners to “pull” two items into alignment; that’s a good way to increase friction, and with that, galling. (It’s also a good way to damage the threads, too, which also increases the chance of galling!)

Evan had some input here, too. “There are some specific cases where it’s good to be cautious, like stainless-on-stainless hardware. Knowing the signs of when a fastener is starting to gall can save headaches. When the fastener you’re using becomes hard to turn despite no obvious obstructions, that’s bad news! I’m probably too paranoid, but I clean or replace hardware pretty frequently when I’m putting things back together.”

I watch your videos and you just crank bolts home, Lem, yet you tell us to use a torque wrench

Here’s that point from earlier I promised we’d revisit. Fast answer: The reason we don’t show me torquing things to spec in the videos is actually quite simple: It vastly reduces the length of the videos and the workload on our editors!

The reason your local mechanic doesn’t use a torque wrench is also simple: In the land of flat rate, time is money. Good enough is not perfect, but good enough is faster than perfection. Production trumps perfection as a paid wrench. I think you should use a torque wrench if you can, but if you can’t (or won’t) become overly reliant on the tool, I actually think that’s not a bad thing. I feel one should be able to torque down a fastener by feel.

Why torque by feel?

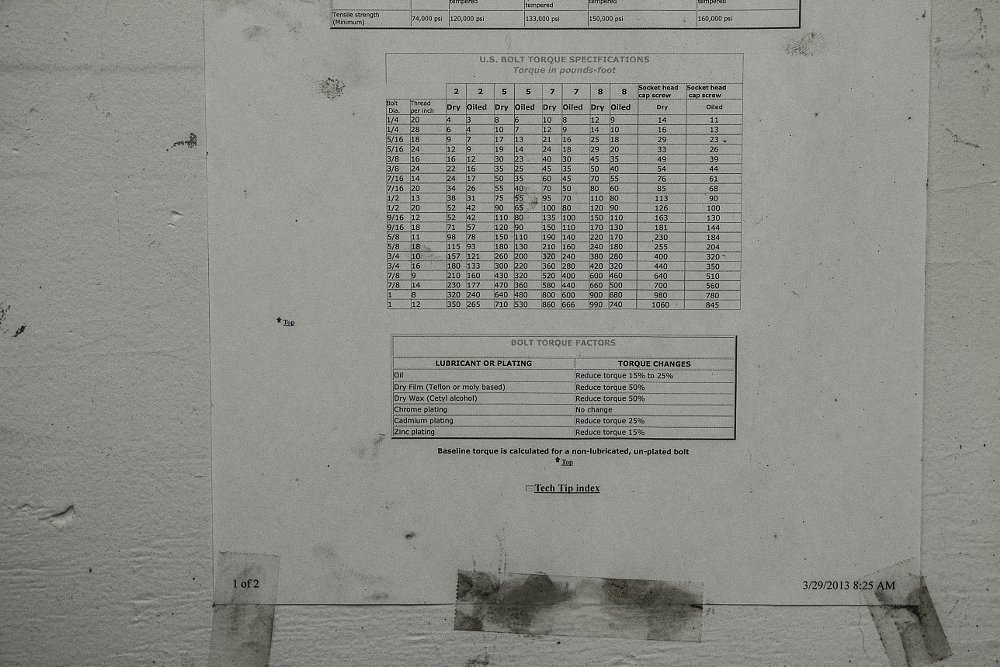

First, there are charts available that give rough outlines on the appropriate torque spec for a fastener (I keep one tacked up on the wall in the shop), but if even if you’re a fairly new wrench, a little common sense goes a long way. You’re not going to be asked to put 168 foot-pounds of torque into a quarter-inch bolt. ZLA Wrenchy Guy Joe Zito accurately noted, for example, that the length of an open-end or box wrench will increase relative to the size of the head it is designed to turn — which is related to fastener diameter, which is chosen due to the necessary clamping force in the joining application for which it is used. Most people instinctively pick up on that. (I will admit to having a friend who was issued a three-eighths-inch ratchet with the handle cut off, because he’s a bit of a gorilla. I think he has reformed a bit.)

Secondly, sometimes specs don’t exist or they’re not relevant. The first torque wrench wasn’t patented until 1931, and torque values didn’t become common until well after that. I have early Harley manuals, and I don’t think I have torque values listed until some time in the Panhead era (1948-1965). This means often a mechanic had to use a “special tool,” designed to a particular length by the factory, or, barring that, his brains!

You may be thinking this is a ridiculous example in 2019, but I think the thought has merit. If you’re traveling along on your motorbike and you need to perform a repair in the field, it may as well be 1930. You likely are not carrying a torque wrench, and even if you were, you’d also need to have access to the spec itself. (Admittedly, that part may be easy given the proliferation of smartphones, but let’s be honest: No one has a torque wrench in his tool roll.) Perfect, assembly-line torque specs are simply irrelevant at this point. Having acquired a feel for the range of proper torque to be applied to a given fastener is helpful in this scenario. It also helps in the shop, say maybe when a given torque spec has been read wrong or when threads are starting to “let go.” (And if you think I’ve never dialed the wrong number onto my torque wrench after a beer or three, you’re wrong.)

The reality is that many fasteners and applications have a wide range of acceptable values. Proper torque falls along a spectrum, not a fixed point.

Back to the pros for a sec: Zito and his colleagues in one of the shops he wrenched at used to have contests where a bolt would be fastened to a specific, arbitrary torque by hand (no torque wrench), and then checked with a torque measuring tool. This is more than just bragging rights — it’s calibration of the body. I’ve done the same thing myself for years. It’s great practice, and it also illustrates beautifully how a small differences like tool length and thread lubrication can really throw your “calibration” outta whack. You can apply the same idea: Train your hands, and use your noodle when it comes to cranking down on bolts.

With all that said, I use torque specs pretty religiously when possible, especially for engine-related items where deformation (or lack thereof) and clamping force are critical, and chassis components where a failure is injurious. (If you’re into engine building, did you know about torque plates? That’s how crucial fastener torque consistency can be in an engine.)

Long story short? Use your good judgment. And if you're not sure you possess good judgment, remember that it comes from experience, which in turn is derived from bad judgment. RTFM. I'm not saying never deviate from it, but it's usually prudent to know the rules to the game before breaking them.