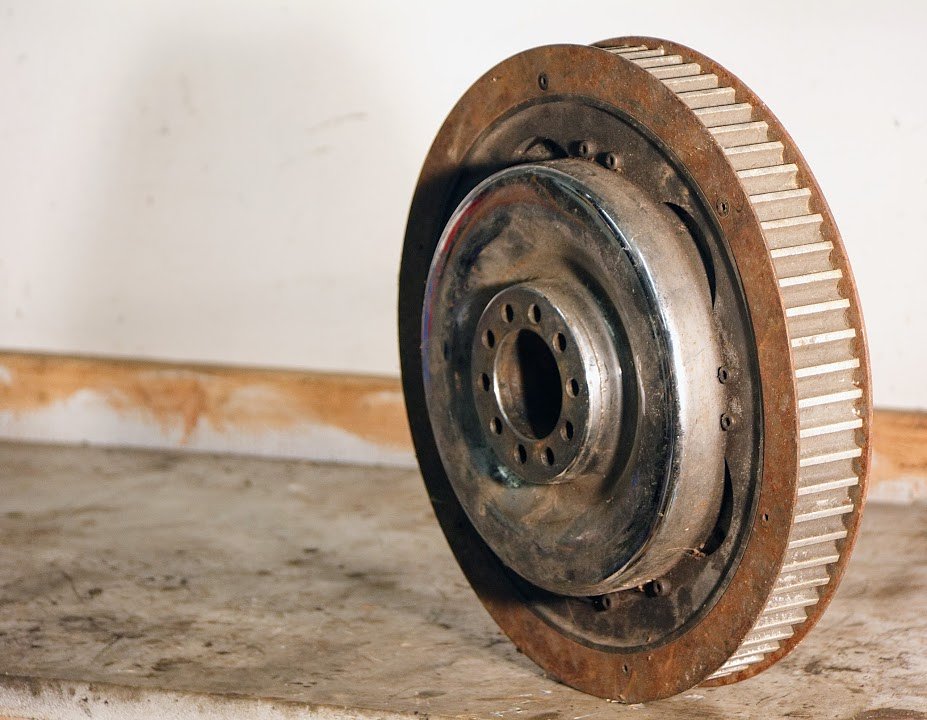

A good friend of mine, Hutch, was throwing something on the scrap heap and offered it to me.

I often take busted-up motorcycle parts and weld ‘em together for desk art or bike show trophies, so he usually runs them past me for that purpose. The part in question was a Harley-Davidson brake drum, from a mechanical rear setup, modified to use an aluminum belt pulley where the sprocket should have been. “That bike must have been hideous,” Hutch said.

This probably means little to you unless you’re a Harley junkie. A little background: This Harley mechanical rear brake would have been installed on a Big Twin from 1937 to 1957. The aluminum pulley would have come from a bike from, at the very earliest, 1982. Hutch’s point was that a bike cobbled together with parts from such disparate time periods was probably an aesthetic mess. In all likelihood, he was very correct.

But I kept that thing. It’s never gone onto a trophy. It lies on my shop floor and sometimes I smile when I kick it out of the way. I kept it specifically because I like the story. Somewhere in a garage in upstate New York during the Bush administration, somebody with more ingenuity than money said, “Ha! I can rework this pulley here, see, and then I can mate it up to this brake drum, and voilà! I can make my motorcycle go and stop!”

I like that. The part has its own story and we were able to discern it just by “listening.” This sort of thing happens a lot. Parts speak. Many of them have interesting things to say. For instance, not long ago, Helen, one of our video editors, had a little unplanned fender-bender with her Suzuki. We had it on the RevZilla shop lift, and we were replacing some busted pieces with some parts from the salvage yard. Helen was doing the work and I was chiming in where I could. She announced she was done with the brake work, but I told her she missed a step.

I told her to try to figure out where she made her mistake by looking at the part and considering its function. I don’t think poor Helen knew what I was trying to get at, so I pointed out to her a little nub that Suzuki had welded onto the pedal. The post had a little button-head cap on it, and I asked her to take a second to think about why Suzuki might have gone to the trouble of welding that little post onto the brake pedal.

In a few moments, she had surmised that something probably affixed to that post, and that the button head probably kept something from sliding off. I watched and remained silent. A few minutes later, Helen had her pedal return spring correctly installed.

That brake pedal told her its story. It waited in a pile until it got its spring post welded on, and then it was ready. America is no longer quite so dominated by manufacturing. As such, it can be easy for Americans to forget — or not even know in the first place — that simple things, like that post, represent lots of man-hours and materials.

I can’t help but try to imagine some Japanese dude, maybe in Suzuki’s Toyokawa plant, spending eight hours a day welding those posts to brake pedals. There was a runner bringing boxes of those posts to the welder when he ran out. Eighteen years after the weld puddle holding it in place cooled, that little post and its design communicated with Helen. On face value, it told her something about its function in this motorcycle's life, just hanging out on that pedal. To me? That one piece explained one employee’s whole reason for punching in at that manufacturing facility.

One of the other things I think is neat is the evidence of human interaction with a part. Early in my antique career, a good buddy of mine taught me a quick way to verify if a set of Fat Bob tanks were original or reproduction. Now, there’s a good list of clues one can use to help figure this out, but this particular one was fast, easy, and nearly foolproof: feel around near the portion of the tank that gets mounted to the rear for a little teat.

I did this unquestioningly for a while, and it was correct — every set of Knuck and Pan OEM H-D tanks I found had that teat on the back. Many OEM tanks did not have it. On some genuine OEM tanks, it had been ground off or buried in body filler before I was born, but if a set had those little nipples on there, the tanks were always legitimate.

As I got better at tank identification, I learned other ways to vet a tank. (Shift gate mudded over? Feel around inside the left filler hole for the bungs. Are the tanks 1948-’50, or the pretty-rare ‘47 only? Check for finger-sized indents on the bottoms for the newfangled Pan tops. Stuff like that.) But I wondered about those nipples. Why were they there?

Evidently, the tanks were paired up with each other for the painters. A thick piece of wire was brazed onto them so a left and a right would be kept together. The painters would clip the thin rod, grind or sand the spot of braze, prep them, and then shoot ‘em. But this was a production facility. They didn’t perfectly smooth over every single blob of braze. They knocked them back, removed any rough edges that would cause the paint to be thin, and called it a day.

That’s why those little nubbins can be found on those tanks. Each time I run into a set in someone’s barn or at a swap meet table, I instinctively go to the rear of the tank. Yeah, I’m trying to make sure they’re worth the huge amount of money I will likely fork over for 'em, but I also think it’s nifty to put my hands in the same spot some painter did during the Depression. Imagine that Milwaukeean whose hours got slashed, probably clinging to that job, hoping to hold on financially until America got itself out of the economic doldrums and business picked up.

Later tanks? Imagine a post-war American laborer, working on that same equipment that had served faithfully for so many years. Just think, America’s future at that time must have seemed to shine as brightly as the paint coming out of his gun.

I also like when I can figure out why an unconventional part was employed. I’ve got a Beta dirt bike, for example, and when I went to pull the shock linkage, I realized the flange bolt wouldn’t clear the brake linkage. As I groaned, my fingers felt something weird on the bolt head. I stuck my kisser down in there to see what was going on, and sure enough, the flat on one side of the hex was machined all the way down into the flange, specifically so one could rotate it and just barely sneak the bolt out for normal lubrication.

That’s neat to me. Some Beta employee will forever have my gratitude. At some point, that guy tried to assemble that bike, and realized the bolt just… wouldn’t… fit. He probably got ticked off, took out his grinder, buzzed a flat onto the flange, and found it would pass by the brake linkage bracket by the hair on its chinny-chin-chin. Maybe he explained this to one of the parts acquisition people over Peronis in a little bistro. It might have been far more formal — but maybe not.

Perhaps there’s a little fiction and some artistic license on my part, but all these little pieces I run into have fantastic tales to tell — deeper, more personal stories about the motorcycles they are found on. You’re here. You like to read. Maybe it makes sense to stop and listen to the bike in your garage. It might have a few anecdotes you'd find interesting.