Have you seen those shows on TV where they build custom motorcycles?

Of course you have. You know the plot. Everyone’s in a big damn hurry, and if the bike is not done really soon, some people are going to be yelling for reasons that are unclear. Then everyone puts the pedal to the metal, works a few sleepless nights, a brand-new bike is started for eight seconds and pronounced road-worthy, and the credits roll.

Every person I know in real life builds very differently than the big-name guys on TV. It doesn't matter if you're an amateur or a pro, or if you're wrenching on a Harley or a Honda. We all go through the same maddening events, which I present uncut and unedited, in proper chronology.

Phase One: Plotting

“Guess I ought to throw together another bike, hon. I pretty much have all the pieces I need, ‘cept for a few odds and ends.”

I spout some variation of this to my bride once a year. The “pieces” usually amount to something like a set of neck cups and bearings, a really cool taillight, and some handlebars that I can’t use on any of my existing sleds. My wife's dutiful nods of approval over the years are a testament to her imminent canonization.

Phase Two: Gathering parts

I start by spending an obscene amount of money to scrounge up major components. Consider this a perverted effort to bring Phase One’s bold claims to fruition. I score a few “deals of the century,” then address the minor detail of making them work together. Nothing ever fits right on the mutt bikes I drag home, because I do not live in Hollywood. The term “direct-fit” in the land of mongrel motorcycles is a joke, a huckster’s sweet nothings whispered into my ears for the sole purpose of parting me from my money. I have learned that thinking about making dissimilar parts jive is usually way easier than actually performing the work necessary to make my dreams a reality. I suspect beer plays a part in this incongruity.

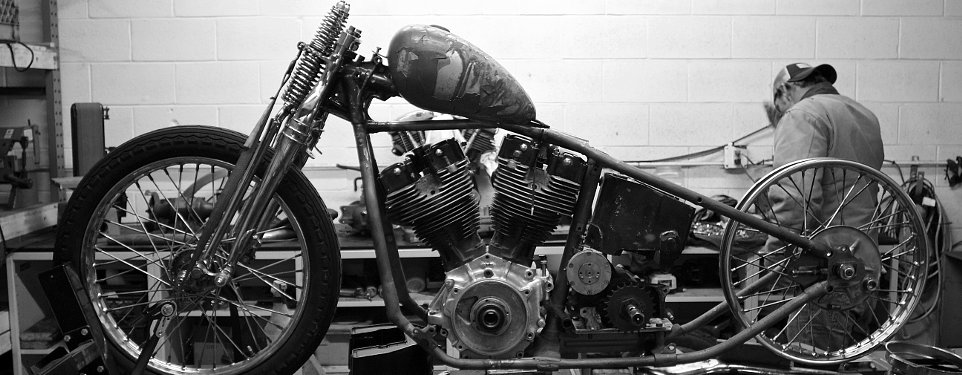

Phase Three: Measuring, cutting, fitting, welding, swearing, grinding, re-welding.

On TV, the pros tack up freshly CNC'd parts with the TIG stinger, step back, look at how perfect it is, and then finish off the weld. I find my sequence of events unfolds differently.

First, I spend an absurd amount of time cutting, grinding and fitting. Then, I burn the item in place. (With a MIG machine. I am hoping some day that an enormous blue, grey, or red machine shows up on the doorstep for free, all because of these sweet Common Tread articles.) When it's done, I do stand back and admire my work. Inevitably, anything I’ve done beautifully on the first pass will interfere with another part, presenting the opportunity to stay in Phase Three for a while longer until I finally make something correctly.

I wonder if swearing and grinding out boogers, bird turds and popcorn makes for good ratings.

Phase Four: Waiting

Wait for paint. Wait for powder. Wait for chrome. Wait for parts to ship. Wait for the wrong parts to ship back. Sit on the bike and make “vroom” noises. That’s how my winter is spent. Unlike the TV programs, there is never a day where eight knowledgeable craftsmen hand-deliver my parts and take the time to explain their individual nuances. Instead, I just wait for the Big Brown Truck. My wife’s opinion notwithstanding, this severely cuts down on the amount of time I spend in the garage. On the other hand, maybe she’s right. I am still out there the whole time, but I am drinking and chatting, not working.

Phase Five: Final assembly

I begin this phase by damaging a motorcycle part that has just received expensive paint, powder, or chrome. (Typically, I only do this on parts that will levy a painful financial blow.) I then have to decide whether to run it the way it is and let it irk me every time I see it, or simply pay to have it re-done. Only then can the actual wrenching begin, followed by a last-minute decision to modify something and not stick to the plan.

Phase Five Point Five: Nickel and diming

This is where I am right now with my current project. This phase is entered when a builder is forced to procure all the little pieces that were too insignificant to order months ago because “they’re just a few bucks!” These items include a master link, brake fittings, exhaust gaskets, and grips. Phase 5.5 (Or maybe it should be “Phase Five and Ten”) has officially begun when I notice my shipping and handling charges consistently outweigh the cost of the parts.

Phase Six: Startup

This portion of the project never resembles TV. Rarely does a bike fire up and need nothing more than a simple idle adjustment. I roll it out of the shop and then kick and kick and kick. (Why do they always have electric-start bikes on TV?) Did I mention I wind up doing this on the morning of a run? Time management eludes me.

“OK, OK, no big deal. Maybe it’s got a small intake leak! Hang on here, the pushrods are out of adjustment.”

Once it’s running, I go on a maiden voyage. (This is often called the “shakedown.” I believe that is because the bike literally shakes down to the ground all the parts that are not securely fastened.) I then get to see how I hosed myself ergonomically. (”Gee, those footpegs are high.”) Finally, I take some time to make minor repairs. (“Where the hell is the taillight? Did that fall off?”)

And there’s not even a Hollywood producer around. Pity.

Phase Seven: Thanking

Here’s the only serious step in here — and it’s one I never see on TV.

I leave cold suppers on my wife’s table, miss my boy’s swim meets, and deplete the parts stashes of my friends. I don’t get to scream at people like they do on the television programs. I simply grovel and grin like a junkie, hoping to hang on long enough to get my next fix. So I try to let everyone know how much fun I had, and how cool the bike is, and how much I appreciate them helping me get it together.

I love putting bikes together. I couldn't care less if it's a chopper or a minibike or a streetfighter. This process is not even a little bit like TV, but it is still more fun than a sackful of puppies. I left out all of the beer, and the friends who come over to help, and the friends who come over just to break horns, and also the beer. Gosh, there is a lot of beer. Some folks are more organized at this than I am, but I think at some point we all take a moment to acknowledge the absurdity of what we’re doing. Whether it’s a cut-up job on a GT750, or a Rudge restoration, we all stumble.

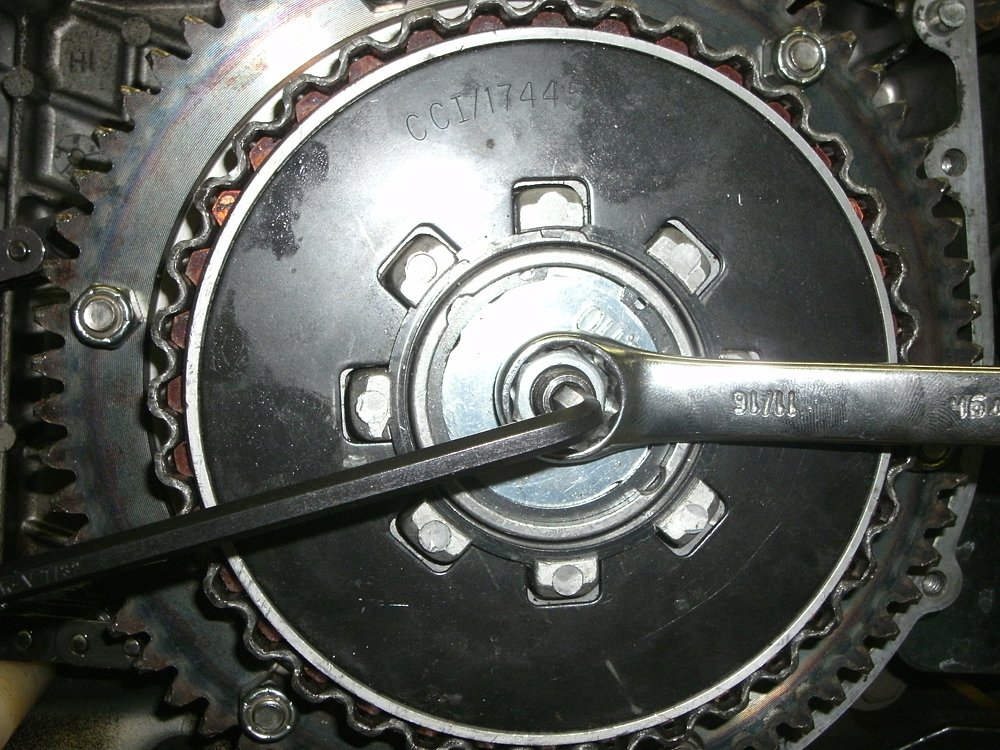

Good Lord, where are all my nine-sixteenths wrenches?