“Friendly.” That’s one of the words that Kawasaki brass used to describe their supercharged, 998 cc, $17,000 naked bike, the 2020 Z H2.

Of course this is from the same folks who describe their Ninja 400 as “powerful” and the Versys 300-X as “sporty.” As with most motorcycle marketing material, that means grains of salt should be taken in abundance. But after spending some time with the Z H2, and after riding it around a race track, a NASCAR oval, and a full day on the street, a funny thing happened. I started thinking about how friendly it is.

The H2 family tree

The Z is Kawasaki’s latest addition to the supercharged H2 lineup. At the top of the family tree is the H2R, a $55,000 sport bike first introduced in 2015 that’s caked in carbon fiber, produces a claimed 310 horsepower for a top speed of around 250 mph, and is only legal to use on a closed course. From those fire-breathing loins sprung the H2 (sport), H2 SX (sport-touring), and now the Z H2 (naked). Like making a copy of a copy, each subsequent model has been a slightly blurrier version of what came before.

The H2 is the street-legal version of the H2R. It gets pedestrian things like mirrors, blinkers, and a headlight, along with a detuned engine that makes a very un-pedestrian 230 horsepower with a sticker price of $29,000. In 2018, Kawasaki unveiled the SX model, which is, in turn, a detuned version of the H2. The SX is down to 200-ish horsepower but has a larger gas tank, roomier ergonomics, and a revised chassis to support luggage and a passenger. While initially you could buy the SX without luggage for $19,000, Kawasaki USA is only offering the SX SE+ for 2020. That’ll set you back $25,000 but gets you electronic suspension, Brembo Stylema brake calipers, a quickshifter, and the best saddlebags in the business. After all that, we’ve finally arrived to the Z H2.

Put simply, the Z H2 is the biggest departure from the H2 family we’ve seen yet. The hypernaked (as Kawasaki calls it) still has a supercharged engine but it’s been re-tuned yet again for more mid-range grunt that is said to result in about 197 horsepower and 101 foot-pounds of torque available at 8,500 rpm. For reference, the SX made the same torque but at 9,500 rpm.

And the changes don’t stop there. The trellis frame is all-new. The two-sided swingarm is new. It’s got a handlebar instead of clip-ons. The brakes have mid-spec Brembo M4.32 calipers and the suspension is no longer electrically adjustable. Instead, there’s some Showa hardware that you have to adjust by hand, just like grandpappy had to do in the war. So if you think that someone just took an H2 or an H2 SX and removed the windshield, think again.

All of these changes were motivated by two goals: Make the machine more affordable and more approachable for everyday riding. Of course, most people don’t think of a $17,000 motorcycle as affordable, but compared to models like the Ducati Streetfighter V4 S or the KTM Super Duke R that can stretch to almost $25,000, it’s actually something of a class bargain. And while the Z may have lost some of the high-end brake and suspension components of its siblings, it still comes standard with a quickshifter, cruise control, a full-color TFT dash, slipper clutch, four ride modes, cornering ABS, and adjustable traction control that’s informed by a six-axis IMU. In other words, damn. It's still $17,000, but that’s a lot of motorcycle.

Riding the Kawasaki Z H2 on the roadrace course

The Z H2 isn’t being touted as a track-focused machine, but it’s still powerful in a way that can be problematic to explore on public roads. So, Kawi opted to start us off with a full day of riding at Las Vegas Motor Speedway. A couple of morning sessions on the outer configuration of their roadrace track followed by an afternoon of going WFO around the 1.5-mile NASCAR oval.

This is probably a good time to point out that I’m not much of a track-oriented machine myself. I’ve done a handful of track days and have received some amazing track-riding mentorship from guys like Zack Courts and Ari Henning, but at the end of the day I’m a firmly average rider when I’ve got a set of leathers on. While I was extremely excited to spin some laps, I was also nervous about my ability to wrangle a supercharged liter bike around a track I had never seen. To make matters worse, the ambient temperature when we rolled up in the morning was about 40 degrees. Cold asphalt, cold tires, and somehow, sweaty palms.

My first few laps were an exercise in caution. Get to know the course and try not to crash a fancy motorcycle that only has 200 miles on it. Eventually, I came around to the front straightaway and figured it was time to start doing my job. Clenching all my body parts that would clench, I wound the throttle all the way open, fully expecting that the forced induction from the supercharger would either flip me into a nearby Cirque du Soleil show or bend space and time until I emerged in a parallel dimension.

Of course, neither of those happened. Instead, the bike just accelerated. Hard. Smooth. Controllable. If you didn’t tell me there was a supercharger bolted to the engine, I wouldn’t have guessed that there was. At least, not until I let off the throttle and heard the chirping sound of excess boost pressure being pushed out the blow-off valve.

Everything felt remarkably normal and predictable — for a 197-horsepower monster capable of face-melting speed. And as far as my loop-out fears, there was little drama with the front end. I was initially riding in the “Road” setting, which means you get full power, but Level 2 of traction control. With an aggressive right wrist, the front wheel would pop off the ground by an inch or two but immediately settle back down, thanks to ignition cuts and airflow adjustment happening every five milliseconds. When riding in “Sport,” the electronics maintain full power but drop TC to Level 1. This allows for more wheel slip and more sustained wheelies, but it still won’t let you loop the bike out. You can give it the full beans and the front wheel will just float, hovering a few inches off the pavement until you either shift gears, let off the gas, or die of old age.

The only way to turn traction control completely off is to go into the customizable “Rider” mode, in which you can mix the traction (Levels 3, 2, 1, Off) and power settings (Low, Medium, High) to your liking. I experimented with TC off, which is certainly fun if you want to lift the front wheel a bit higher, but for most applications and my comfort level with wheelies I preferred the balance of fun and safety that’s afforded in Level 1. It’s an incredibly seamless affair, with only a flashing orange light on the dash to indicate when the bike is working hard to make you look good and stay upright. Fear not if you selected the incorrect riding mode before you took off, because you can change those modes and settings on the fly.

Adding to the suite of electronic doo-dads is the Kawasaki Quick Shifter and slip/assist clutch. The quickshifter works both up and down as long as you’re above 2,500 rpm and never once did it falter. Just tape the throttle open, keep your fingers wrapped tightly around the grip, and enjoy the ride while your foot effortlessly escalates your transmission position (best said in the voice of a late-night radio DJ). Meanwhile the slip/assist clutch makes sure that the bike keeps the plates forced together during hard acceleration for better drive and then lets them slip apart during aggressive downshifting to avoid wheel hop or engine lock-up. All good stuff, all working beneath the surface to make you feel like a better, more confident rider.

Compared to the SX SE+, the Z has smaller front rotors (320 mm versus 330 mm) and less extravagant calipers (Brembo M4.32 versus Brembo Stylema) and yet I found the brakes to have a progressive feel with good stopping power and plenty of feedback. They don’t have the stop-on-a-dime strength you get with bigger rotors or beefier calipers, but in some ways that made my corner entry and trail braking easier to finesse. In a word, the brakes are forgiving. Powerful enough to forgive when I came into a corner with too much speed but gentle enough to forgive when I mashed the lever too hard in a mid-corner adjustment. If you’re the kind of rider who loves the snap of Ducati or BMW brakes, you’ll probably be disappointed with these, but I think it’s a reasonable amount of stopping performance for most people, especially on a bike that’s intended to be ridden on the street.

The handling presented even more spec-sheet contradiction. While the Z H2 has a wet weight of 527 pounds (add another 2.2 pounds for an emissions canister if you live in California), I never once thought about the weight as I was riding it around the track. In fact, I found myself exerting far more energy holding on to the handlebar during hard acceleration or braking than trying to muscle the bike from corner to corner.

A lot of that has to do with the fact that the suspension controls the Z’s girth with grace. Both the fork and shock are adjustable for compression, damping, and preload. We dialed in two additional turns of preload in the fork and one more turn of preload in the shock for our track sessions, but other than that all settings were bone stock. In spite of all the weight being thrown around, I didn’t notice any issues with front-end dive on corner entry or exaggerated squatting or wallowing on corner exit. Sure, it’s sexy to say that your bike has some exotic, gilded suspension hardware, but Kawasaki has done an admirable job removing those pricey components without compromising too much on real-world performance.

That being said, there is definitely an elephant in the room with the Z H2 and it weighs somewhere in the neighborhood of 60 to 80 pounds. Almost every other bike in this hypernaked class, Japanese or European, tips the scales somewhere in the mid-400s. So no matter how much I tell you that the weight of the Z H2 isn’t noticeable while riding, there’s no way that it’s going to feel as light as motorcycles that weigh some 15 percent less.

I asked the Z H2 project manager, Koji Ito, exactly how much weight the supercharger added to the bike and he laughed before saying, “Good question. Secrets.”

He went on to explain through a translator that while Kawasaki won’t disclose the exact weight their supercharger adds, people should remember that it’s not as simple as strapping an impeller to the engine and calling it a day. There’s also reinforcement that gets added throughout the machine so that it can reliably handle the kind of force the bike is capable of producing. So there you go, those pounds are the price you pay for the bragging rights of a motorcycle with a supercharger.

Riding the Kawasaki Z H2 on the NASCAR oval

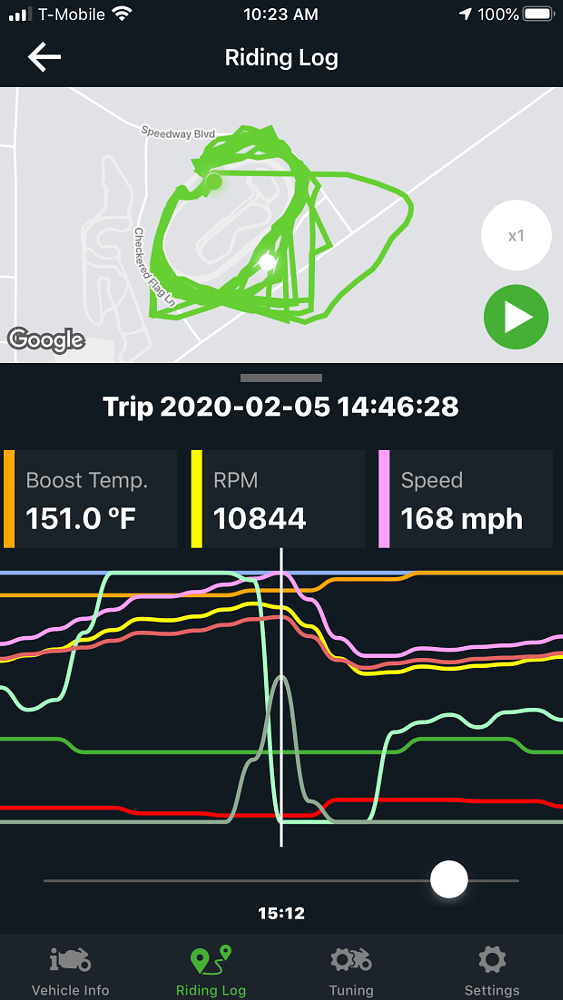

Normally, riding a motorcycle around the twists and turns of a race circuit is the highlight of a press launch. But after we wrapped our morning session at the track, Kawasaki brought us over to the NASCAR stadium where we had free rein to stretch the legs of the Z H2 around a 1.5-mile oval with 20-degree banking. Not only did this allow us to experience sustained high-speed performance, but we also had an opportunity to explore the features of Kawasaki’s Rideology app that connects to the bike via Bluetooth. When downloaded to a phone and hooked up to the motorcycle, the app allows you to see a breadth of data collected from the ECU: rpm, speed, throttle position, lean angle, boost pressure, boost temp, brake pressure, and the list goes on. All of the data is GPS-specific (as long as you’re riding with your phone) so you can see exactly what your motorcycle was doing and exactly where it was happening.

The first session out, my first time ever riding on a banked oval, I spent 20 minutes confronting my fear of running into a concrete wall while going over 100 mph. No matter how many times I came barreling into the banked corner, determined to hold the throttle open and trust centripetal force to maintain my traction, I always grabbed the brakes too early. When I came back into the pits, I opened up the Rideology app to check the data log and saw that my top speed was recorded as 140 mph. Not. Fast. Enough.

But here’s the thing. This whole experience was a fantasy. Normal people who buy the Z H2 probably won’t take it to the track and they almost definitely won’t take it around a NASCAR oval. What they’re far more likely to do is ride it on a cold morning through a state park, going the speed limit. Wishing that they were going around a race track. Which brings us to...

Riding the Kawasaki Z H2 on the street

On day two of the press event, we headed to the Valley of Fire State Park about 50 miles northeast of Las Vegas. The freeway ride out there was a sobering return to reality from the day before, even though the bulky nose of the Z H2 provided better-than-expected wind protection and the flat, wide seat kept things comfortable. The seat-to-peg ratio was also a good fit for my six-foot frame, with fairly neutral peg placement in relation to my hips. Heated grips would have been nice, as temperatures once again dipped into the low-40s, but I’m an Arizona native who wants heated grips on everything — even when it’s 75 out.

Before long, we arrived at the park and it became clear why Nevada has gone to such lengths to preserve the place. The landscape is a mosaic of red stone formations, shifted and shaped by the wind over the course of 150 million years, with swirling lines of sediment that make it look like Dr. Seuss dabbled in terraforming.

The winding road through the park was a surprisingly bumpy ribbon of asphalt and I quickly noticed how harsh the Z H2 suspension felt out in the real world. I figured the bike must still be on the suspension settings from the track but was surprised when a Kawasaki tech told me that they had put it back to stock for our street ride. At about 165 pounds, I'm apparently on the light side for their baseline settings. Annoyingly, the shock does not have a remote preload adjuster. Making changes on the road required two people and some tools. It’s not the end of the world, but in a class where many bikes can make these changes with the press of a button, it was a prominent reminder of where Kawasaki had cut some corners to meet a price point.

After we got the suspension situated, the ride felt a lot better and I was eager to make some distance. The park spans 46,000 acres and our loop was supposed to cover 100-plus miles before returning back to the hotel. Unfortunately, as is the issue in many beautiful state parks, distance does not come easy. Between wildlife-gawking tourists stopped in the road and a speed limit of 25 to 35 mph, we often found ourselves in a tragic congo line of corked horsepower.

Over the course of these slower sections, I started to notice the abrupt throttle response that occurs right when you get on or get off the gas. This isn’t some earth-shattering issue that ruins the bike, but it’s worth noting that Kawasaki still hasn’t completely solved their fueling gremlins. It’s a known issue among the H2 lineup and it’s even an issue on my 2016 Versys 650. Lots of people say that an ECU reflash can do wonders to smooth things out but I’m still hoping that Japanese OEMs can start to deliver a more refined response right out of the box.

As we edged our way out of the park, we finally got back to open road where the Z H2 was all too eager to make some passes, burn some fuel, and to reel in the twinkling lights of Vegas. The Z has the same five-gallon gas tank as the SX and it can get reasonable fuel economy (35 to 45 miles per gallon) if you ride it in a controlled manner. And since the Z also comes standard with cruise control and a crystal-clear TFT display, it doesn’t take much effort to set your speed at a decent (see: legal) pace and let the engine gracefully whisk you along.

So, the fueling isn’t perfect and the suspension isn’t as easily adjustable as it should be. Otherwise you’ve got yourself an extremely powerful, well appointed naked bike, the only one in the world with a supercharger, that can be had for $17,000. Which leaves us with the questions asked by Lance when this bike was announced: Why does this bike exist? And who is going to buy one?

Summing up the Z H2

We live in a simultaneously strange and wonderful time for motorcycling. If the Z H2 had been built in the late 1970s, as a true successor to Kawasaki’s notoriously dangerous 750 cc two-stroke triple, the H2 Mach IV, people would have surely crowned it the Widowmaker 2.0 (if phrases like "2.0" had been around in the '70s). If it didn’t have traction control, lean-sensitive ABS, a slipper clutch, and variable ride modes, this is precisely the sort of motorcycle that would rightfully gain a reputation for being deadly. But in today’s world, with all that technology, the Z isn’t considered a widowmaker — it’s considered friendly. And after spending a couple days riding it, I have to admit that calling this bike “friendly” isn’t as ridiculous as it sounds. I am an average track rider who managed to lap the Z around a cold, unfamiliar circuit in the morning, and then take it around a NASCAR oval at almost 170 mph in the afternoon, all on the first day I rode it. The top speed of a Mach IV? 126 mph.

Motorcycles today have far surpassed the abilities of most riders. And I don’t think we need to punish ourselves for that. We don’t need to say that motorcycles like this are unnecessary because, in this day and age, especially in the United States, almost all motorcycles are unnecessary. And the same company that makes the Z H2 also makes the Z400 — one of the best beginner motorcycles you can buy. Kawasaki has not abandoned new riders in order to build some unobtanium flagship, but rather they’ve decided to build some unobtanium flagship so that they just might inspire some new riders.

And ultimately, they’re bound to sell a few of them. Maybe it’ll be an old-school rider who remembers pining for the Mach IV but was afraid of getting widow-made. Maybe it’ll be the person who just wants something different — the only supercharged naked option there is. Or maybe it’ll be someone who just really loves Sugomi styling! (LOL. Just kidding.)

The truth is that I think the buyer could be a lot of different people, because it’s this kind of star-reaching motorcycle that inspires kids to put up posters on the wall and strangers to come up and ask questions. It’s not a rational, reasonable machine that anybody needs. But what poster-worthy motorcycle ever has been?

| 2020 Kawasaski Z H2 | |

|---|---|

| Engine type | Liquid-cooled, supercharged, inline four, four valves per cylinder |

| Displacement | 998 cc |

| Bore x stroke | 76 mm x 55 mm |

| Compression ratio | 11.2:1 |

| Power/torque | 197 horsepower; 101 foot-pounds torque |

| Transmission | Six gears, chain final drive |

| Front suspension | Showa SFF-BP fork, adjustable preload, compression and rebound damping |

| Rear suspension | Showa shock, adjustable preload, compression and rebound damping |

| Front brake | Twin 320 mm discs, radial-mount Brembo M4.32 calipers; ABS |

| Rear brake | Single 250 mm disc, single-piston caliper; ABS |

| Tires front/rear | 120/70ZR17; 190/55ZR17 |

| Steering head angle/trail | 24.9 degrees/4.1 inches |

| Wheelbase | 57.3 inches |

| Seat height | 32.7 inches |

| Tank capacity | 5.0 gallons |

| Wet weight (full of fuel) | 527 pounds |