Denis Sire, a French graphic novelist who specialized in hot rods and motorcycles, succumbed to cancer recently. He was buried in Paris’ famous Père Lachaise cemetery.

Americans know Père Lachaise because it’s where Jim Morrison was buried. Sire would’ve loved that, but besides the Doors’ famous singer, Denis is in terrific company: Oscar Wilde, Edith Piaf, Frederic Chopin, Balzac and Proust; among visual artists Modigliani, Delacroix, Ingres, Pissarro. Can you imagine them all drinking, smoking, singing, and arguing through the nights?

For Black History Month, Common Tread is featuring this article from four years ago. It's the little-known and highly unlikely story of how an unknown half Native American, half African-American drag racer in the United States became a famous white guy in a graphic novel in France.

As far as I know, Denis only traveled to the United States once; he spent a few days in Indianapolis, illustrating a story about the Indy 500 for a French magazine. However, many of his bandes dessinées were set in the America of rock ’n’ roll and hot rods. He was living proof that although the American government is often reviled around the world, American culture is very, very popular.

Sire loved sprint cars and Buddy Holly, but he really idolized land-speed racing on the Bonneville Salt Flats. That was how I got to know him.

Back in 2003, I was in Paris at a vintage bike show. A gaggle of French bikers gathered around an old Triumph, elbowing each other and pointing at it.

I heard one say, “C’est le monstre du lac salé!” (Literally, “That’s the Salt Lake Monster!")

That piqued my curiosity, so I asked the owner, a guy named Laurent Romuald, if the bike was an old Salt Flats racer. “No,” he told me wistfully, “but it’s my dream to run it on the Bonneville Salt Flats.”

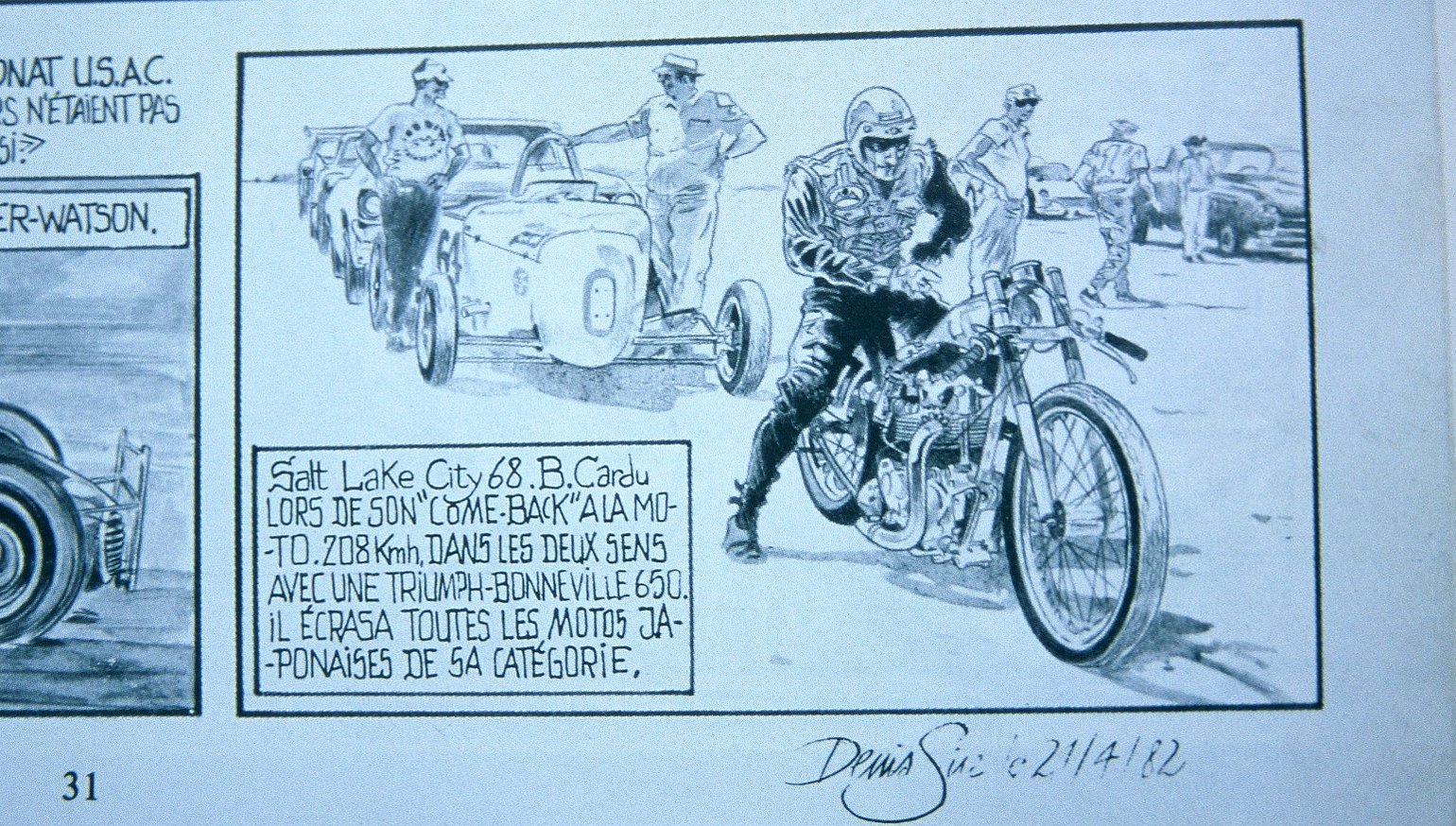

They say art imitates life, but Laurent’s bike was a case of life imitating art imitating life. His bike was a replica of one that figured in a comic book written and illustrated by Denis Sire, whose bande desinées were very popular with French bikers in the 1970s and 1980s.

The story appeared in a comic book called 6T Melodies. It was so popular that Laurent decided to build a replica of the bike from the comic. “I was born in 1959,” he told me, “the same year as the Bonneville.” He grew up to become one of the top French experts on British twins, with a beautiful shop on the outskirts of Paris called Machines et Moteurs. He called Denis Sire to tell him his plan.

“Good luck,” Sire replied. Then he explained that he’d made it all up based on a single old photo.

“But,” Denis added, “I think I still have the magazine, I’ll bring it over.”

The two were soon fast friends. They blew up the magazine photo but there wasn’t much detail to be seen there. They also searched for any mention of Nira Johnson in other old magazines, hoping to trace him, but came up empty. So in the same way that Sire had imagined his American stories, Laurent had to imagine the bike.

“I could see it was an early Bonneville motor in a rigid frame,” he told me. “It looked like a drag bike, so as I built it, I asked myself ‘What would an American drag racer have done in the ’60s?’”

The French have held America in special regard since the days of Lafayette; deep in their subconscious, they see the American Revolution as the one that worked. I loved the idea of these two French guys creating an in-the-metal version of an imagined bike, ridden by an imagined rider, in an imagined version of the United States.

I promised them that I’d do what I could do to help them live out their fantasy about bringing their bike over to run it on the Salt Flats. When I got back here, I did my own search for Nira Johnson and also drew a blank. I wrote about Laurent, Denis, and le monstre du lac salé on my blog, and forgot about them for years.

The real Nira Johnson

One day out of the blue, I got an email from a stranger that read, “I’m a friend of Nira Johnson, and I have his old motorcycle. Call me.”

I just about crapped. The stranger — a consulting engineer and AHRMA racer from Nevada named Rodd Lighthouse — had grown up with Nira as a family friend. He’d recently convinced Nira to sell him his old bike. He told me that Nira had been quite a successful drag racer in Southern California in the 1960s. “You may not know that he was a black man,” he added.

He gave me Nira’s phone number and I called him up. Nira laughed when I told him that he was famous, at least to French motorcyclists, as a white guy. It turned out both Nira and I were scheduled to attend some upcoming American Historic Racing Motorcycle Association races at Miller Motorsports Park, about 20 miles from Salt Lake City.

This is why I don’t write fiction; I could never make this stuff up.

I finally got the American side of the tale, from Nira Johnson himself, in September of 2008.

Johnson was at Miller to do a little wrenching for Ken and Rodd Lighthouse, who were AHRMA road racers. Nira and Lighthouse père et fils had trailered the old drag bike up to Miller so I could see it.

Nira Johnson was born in New York of African-American and Native-American parentage. He went to a vocational-technical high school and joined the Air Force after graduating. He flew on B-36 strategic bombers.

“That’s when I got into motorcycles,” he told me. “I learned as I went. I threw a primary chain through a case when I had my first BSA. An Air Force buddy had a background with hot rods. He was from California, and probably inspired me to move to California when I was discharged.”

In 1958, Nira did just that. He got a job at an aerospace company that became Rockwell International, where he helped to make Minuteman missiles and hold the Russkies at bay. In his spare time, he hung with two bikers who raced a twin-engined Triumph dragster they’d bought from Joe Dudek, a legendary Los Angeles tuner. One day when their rider — a fellow named Bill Johnson — didn’t show, they said, “You’re about the same size as him, why don’t you ride it?”

“I liked to keep things reliable,” he recalled. “The pre-unit Bonnevilles had a three-piece crank, and when they went to unit construction, they put in a better, two-piece one. So I used that. I polished it, and took off some weight. I ported it; lightened and polished the rods… I wanted to put in bigger valves but it was too expensive.”

His bike wasn’t overly powerful; he remembers it making about 56 horsepower, but it was light. He even thinned all the gears in the transmission. And, it was reliable. In six years of racing it almost every weekend, he blew up one motor.

“I ran what they called Class B/Gas. In the beginning I ran in the high 11-second range, with trap speeds around 110 mph. At the end its development, the bike was hitting 116-118 mph. Sometimes, when other guys saw that I was there, they’d just roll their bikes right back onto their trucks and go home!”

The time that Nira was photographed on the Salt Flats was the only time he ever raced there. “I was using Harmon-Collins cams, and they had some they said were ‘too radical for drag racing’ so I got them to grind me some of those. Other than that, I just swapped the rear tire and gearing. My bike ran good, but the record was set by Dudek and Johnson, at speeds that were unattainable on gas — they were either running alcohol or fuel — so they ran in the high 140s, and my best runs were in the 130s.”

Not long afterwards, Nira moved to the East Coast for his job and he had no time to drag race. Ironically, he traveled to France for work in 1983, when Denis Sire’s comic book was a bestseller.

“I had no idea I was a character in a comic book over there,” he told me, adding — surely an understatement — “I was kinda surprised.”

The perfect ending that never happened

For the last 10 years, I’ve desperately wanted to bring all three of those guys, Denis, Laurent, and Nira, and both bikes, Laurent’s replica and Nira’s original, together on the Bonneville Salt Flats.

I wanted Laurent to rebuild Nira’s bike and make it safe to run again. In the course of doing that, Laurent would finally learn all the things he’d guessed about. And I wanted to see how the replica compared to the original where it counted, through the traps. I wanted Denis to illustrate the encounter, and I wanted to layer his illustrations into the film. It would have been the coolest motorcycle documentary ever.

I worked on it for years with a producer friend of mine; we pitched sponsors and shot a promotional short. Every year for the last decade, I’ve emailed Laurent to ask, “Do you still have your ‘monster’?” I checked in with Rodd Lighthouse to ensure he still had Nira’s bike. I called Nira to inquire after his health.

My producer and I always thought we were racing against time because Nira was in his 80s. But it turned out the first subject to kick the bucket, Denis Sire, was barely older than me.

In everyone’s life, there has to be one great lost opportunity. Maybe mine was never being able to introduce Laurent and Denis to Nira, and run their two Triumphs side by side down the salt.