It came over in 1966, when aspiring Husqvarna importer Edison Dye entered several riders in a desert race in California’s Imperial Valley. Dye’s light, fast, two-strokes slaughtered the heavy four-stroke machines that dominated racing in those days. In short order, hard-core American off-road riders were flocking to Husqvarna, Bultaco, Maico, CZ, and other European marques.

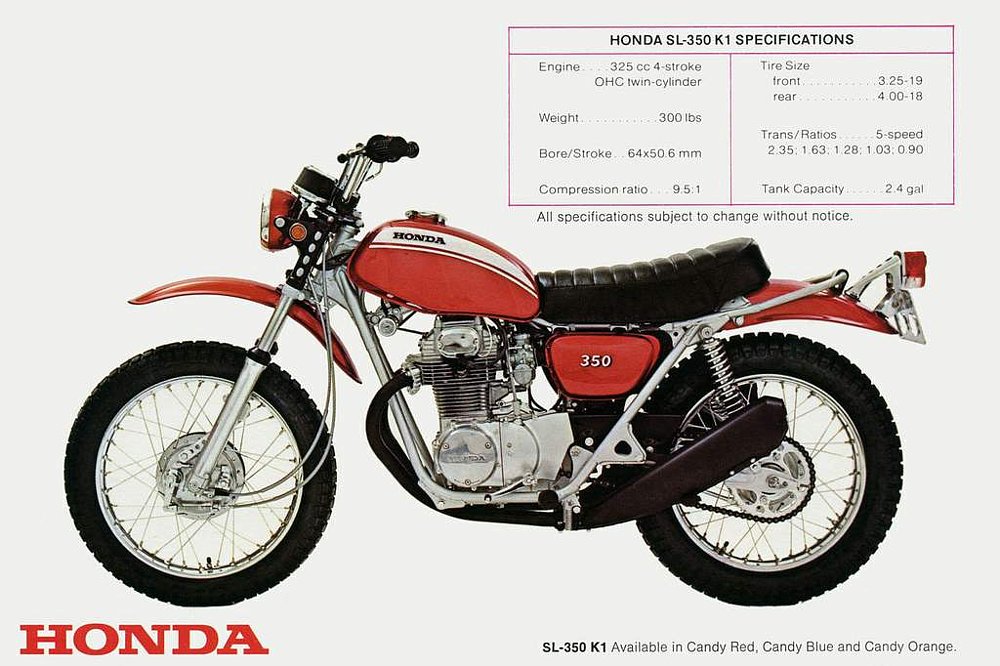

Europe’s two-stroke motocrossers were purpose-built and powerful, but they were prohibitively expensive to buy and repair, and they frequently broke. Meanwhile, Japan Inc.’s response to the growing off-road craze was to modify existing street bikes for dirt use. The price was right and the build quality was generally good, but the machines themselves were heavy, slow, and poorly suited to tracks where big jumps and berms were becoming the norm.

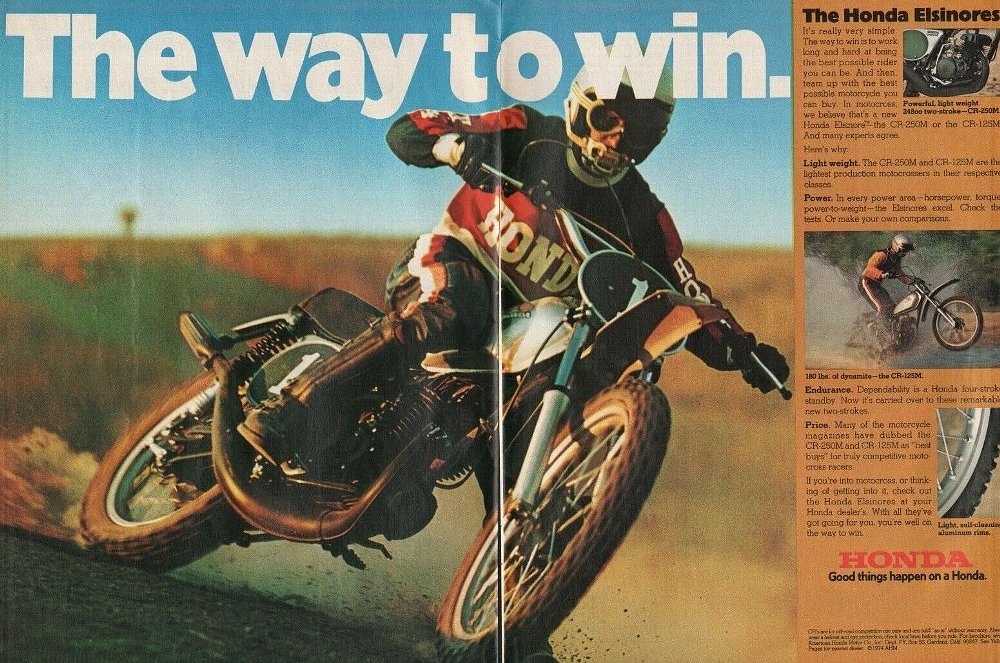

Then, in the spring of 1973, Honda debuted the CR250M Elsinore, its first two-stroke competition motocrosser. “It had all the stuff the CZ and Maico had, but it didn’t break. It shifted better, weighed less, and was quicker than the other bikes. It was just better than anything else, and it was affordable,” says Jones, who won his second consecutive AMA 250 Championship on an Elsinore.

Shortly after the CR250M arrived, the silver-tanked Hondas accounted for the majority of bikes on 250 starting gates across America. The flames of motocross madness were smoldering in the grass fields and forests of the United States, and the fast and affordable Elsinore came in like a hot wind to stoke the fire. It was the right bike at the exact right time. It helped catalyze the off-road craze of the 1970s and forced all the manufacturers to up their game in terms of performance and quality.

Evolution of an off-road icon

The Elsinore received much more than its name from Southern California, because while the bike’s blade was forged in Soichiro Honda’s factory in Japan, it was honed to a razor’s edge by Gary Jones and his father Don.

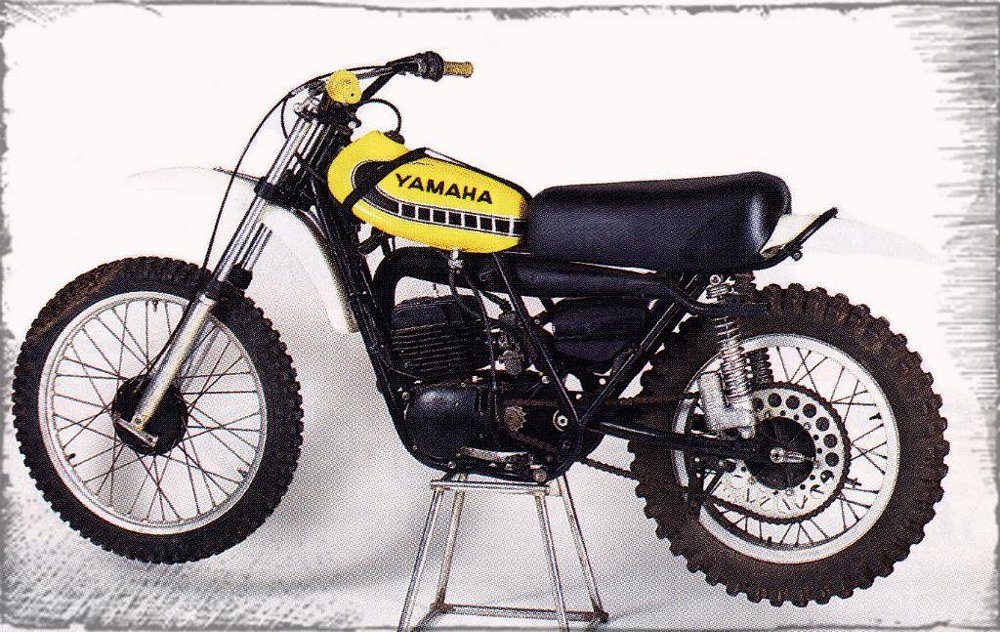

The senior Jones ran a motorcycle dealership in the San Gabriel Valley and served as tuner and fabricator for his son, Gary, who was quickly becoming a formidable racer. With a lathe, mill, welder, a little help from the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, and plenty of experimentation and seat time, Don and Gary developed their 1968 Yamaha DT-1 enduro into a race-winning motocrosser. Yamaha was so impressed with their bike that it used it as the template for the 1971 YZ250. Gary then rode that bike to his first official 250 National Championship in 1972.

Interest in motocross was growing quickly, Honda wanted in on the action, and it was obvious that the talents and experience of Gary and Don would be valuable in developing and campaigning a new off-road model. “We were still with Yamaha when Honda approached us in ‘71,” says Jones, “but we agreed to help assess their bikes.”

“There was a twin-cylinder scrambler and a prototype single-cylinder that was basically half of one of their four-stroke roadrace engines. They were both too heavy, and not fast enough compared to what we were racing. I explained that their bike had to be lighter, and that two-strokes were way faster.” Mr. Honda wasn’t eager to hear that.

It’s a well-known fact that Soichiro Honda disliked two-strokes, and the popular explanation is that high-minded Mr. Honda felt they were dirty and noisy. However, Jones suggests that Honda may have been more concerned with the vulnerable technology sullying the company’s reputation. “Reliability was what he was really worried about. He was afraid of all the ways the end user could screw up a two-stroke and how that would reflect badly on Honda.”

The Joneses and Honda parted ways, and the two parties didn’t communicate for nearly a year. “Then, in late 1972, they showed up with a two-stroke prototype for me to try. It was good, and probably competitive, but dad and I knew it could be better.” Negotiations ensued, and once it was agreed that the Joneses would have autonomy in refining the CR, Gary contracted to race the 1973 season with Honda.

“To tell you the truth, we had a lot of problems with the Works bikes” recalls Gary. The hand-built machines had brittle frames that cracked, and the engines were fraught with problems. After all, Honda had never produced a performance two-stroke before.

“Cylinders seized, and we had a clutch break on the starting line at Daytona [the first round of the season] and couldn’t race that day. Eventually we switched to production bikes, and started modifying them ourselves. We put a reed valve on it, we cut the frame and modified the head angle, and changed the shock angles. The bike was good, it just needed more work, and we knew how to do it. Honda did all of that stuff eventually, but they just wouldn’t move fast enough for us to win on the bike at the time.”

And win they did. The Joneses took Honda’s new platform and turned it into a proper weapon. Gary snagged six wins that season, handily securing the Championship — his second crown in the 250 class, and Honda’s first, with its first-ever motocrosser.

They say you beat the nicest people on a Honda.

Riding “the green stripe” today

The Elsinore was already selling well in mid-1973, and after Jones won the championship there was a proper frenzy. The bike pictured here was produced in 1974, enjoyed extensively for a decade or two, then parked once it was too worn out to run.

After a DT-1 level rebuild, this CR250M crackled to life on a warm fall afternoon at a natural-terrain course similar to the ones Jones would have ridden in his heyday. Magazine reviews from ‘73 praised the Elsinore for its ability to idle — a rare characteristic for two-strokes back then — and this survivor upheld the tradition, popping and snorting along on choke as it wafted a blue haze that Mr. Honda likely learned to appreciate.

The fact that the modern CRF450R evolved from this CR250M is almost hard to believe, like a biologist explaining that antelopes once resembled rabbits. Designed before the days of foot-long suspension travel, the Elsinore looks low and fast, like it’s already flying across the desert even though it’s parked. The seat is just 32 inches off the ground instead of 37, and it’s well padded and wide, a far cry from the rigid rails that provide today’s riders with so much feedback… and discomfort.

As potent and focused as it was considered in the 1970s, the CR250M is surprisingly versatile and easy to ride. It’s incredibly light, for starters, so it’s effortless to chuck around, and the engine is tractable. Even without the torque-boosting reed valve that Don and Gary — and later Honda — added to the engine, power is smooth and broad.

There’s certainly a wave of thrust when you get up on the pipe, but the motor is content to tractor along an inclined trail with little need to fan the light and linear clutch. The transmission is the slick perfection we’ve all come to expect from Honda and the drum brakes are gentle and effective. Suspension action is well controlled, but the seven-inch front and four-inch rear travel figures remind you to pick your lines and stick your landings correctly. Riding gently seems appropriate for a 50-year-old bike, anyway.

A part of me was intimidated to ride the Elsinore. I was expecting a shrieking, hard-to-manage machine with too much motor and not enough of everything else, but the CR250M is a peach. It just works well, and does what you want. And that was certainly part of the appeal in 1973. When magazines felt it necessary to point out that it idled, the forks didn’t leak, and the spokes didn’t come loose after the first ride, it’s clear that riders at the time were largely living in deficit. If your food is regularly overpriced and served cold, a hot meal will really blow your socks off.

The Elsinore impresses even a spoiled 21st century rider, and not just with its nostalgic aura, which is undeniably powerful. Comfortable, quick, and above all fun and easy to ride, it’s not hard to understand why the machine was such a hit with everyone, from casual trail riders to professional racers. And that popularity had a lasting impact.

Out of the lead, but still a winner

The CR250M of 1973, the CR125 “red stripe” of 1974, and the debut of the Gold Wing in 1975 had Honda at the forefront of the motorcycle industry. However, it was still a small corporation, and the oil embargo of ‘73 and phasing out of leaded gas in ‘75 compelled Honda to shift engineering resources toward automotive projects. It was a brilliant business move that yielded the first Civic model and put Honda on the map as a major auto manufacturer, but it left the two-wheeled products lagging, particularly the Elsinore.

But for motocross as a whole, it didn’t matter. The Elsinore had already made its mark, igniting a blaze of interest for consumers and setting in motion a no-holds-barred pursuit for improvement and innovation for manufacturers. Honda raised the bar, and everyone else was working hard to exceed the new standards for performance, price, and quality. The result was a flood of increasingly excellent off-roaders, which were eagerly received by riders.

In the mid-1960s, Americans didn’t know much about motocross, but by the mid ‘70s there weren’t many motorcyclists who didn’t know about it.