I set out to write a quick article about the BMW R 80 G/S. It’s a motorcycle that’s been plodding in and out of my dad’s garage for the past 30 years and, as machines go, it’s part of the family. Then our esteemed editor pointed out that we should probably do better than that.

This is, after all, one of BMW’s most important and influential motorcycles of all time, and Mr. Editor Lance is keen on these retrospective reviews for good reason. Certain bikes deserve some of their history painted on the walls of Common Tread, and maybe a bit of flowery prose about how much we should care about them. If you’re thinking the motorcycling world doesn’t need another history of how the R 80 G/S created the ADV category, you’re probably right and for that reason I won’t try to spell out every last detail. Think of this as a palate cleanser before we get a taste of what it's like to ride a 40-year-old innovation.

Nearly the boxer’s last punch

As with any chin-stroking gaze into yesteryear, it’s crucial to understand at least the context of the times. As with many manufacturers, BMW in the late 1970s was a different company than the one we know today. The wide array of models provided by many motorcycle brands these days was not necessarily the norm, and if there was one thing BMW had yet to conquer it was off-road terrain. Or “Gelande,” to some.

The products rolling out of the Motorrad division of BMW were pretty thoroughly designed for use on the road or street. That’s “Strasse” (or Straẞe) in German. And frankly that part of the business wasn’t exactly whistling along, with Japanese manufacturers fully in stride providing fast and affordable street bikes. Not to mention the fast and affordable dirt bikes, from Japan and elsewhere, which all but convinced companies like BMW from even dipping a toe in the mud.

BMW Motorrad was in sink-or-swim territory, with corporate management telling the new boss of the two-wheeled division, Karl Gerlinger, to succeed or be sold. And what with all of the competition there weren’t a lot of good options, off the roads or on them. An R&D engineer named Laszlo Peres had an idea, though, based on the strange crossbreeding of his work at BMW and a love of enduro riding.

His Bavarian basement build was a bizarre mix of off-road tires and suspension on an otherwise street-ish chassis, and a typical-for-the-time 800 cc boxer engine. Peres’s bosses released him of other duties for three months to work on the prototype, and 18 months later the machine made its world debut. Part off-road, part street, or Gelande/Strasse. In September of 1980, BMW invited motorcycle journalists from around the world to Avignon, in the south of France, to try the new R 80 G/S.

It could have been the dying gasp of BMW Motorcycles, and some motorcycle experts of the day thought it might be. The bike was for sale for $4,800 in 1981, just north of $15,000 in 2022 bucks, and at least a few people asked the rhetorical question of what anyone was going to do with a 400-something pound dual-sport that cost that kind of money. In the mindset of that era, it wasn’t a bad question.

Of course, it’s easy to see now that it worked. The G/S as a competition machine raised eyebrows and finished well all over Europe and was soon crowned king of the Paris Dakar Rally. More importantly, the bike fit into the company plan and succeeded on showroom floors enough to keep BMW Motorrad chugging along. Incidentally, Karl Gerlinger gave the green light to the K 100 as well, a liquid-cooled and inline engine that would lead to decades of K-bike evolution.

A ride back in time

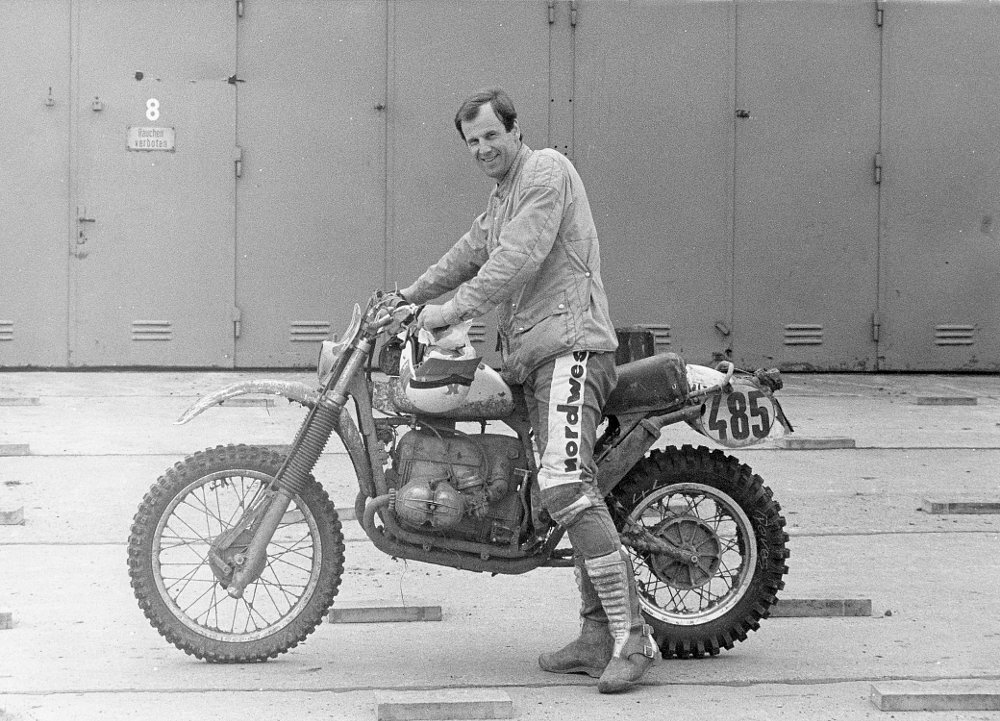

Before submitting a review of this hall-of-fame motorcycle, it’s fair to note that my dear ol’ dad’s G/S you see in these photos isn’t exactly in showroom condition. There are the Jesse bags, fog lights, heated grips, and Corbin seat (reupholstered many times), plus more than 100,000 miles of tinkering, fixes, and wear that the bike has accumulated over the years. Then the crown jewel, an 11-gallon fuel tank from Acerbis, which luckily doesn’t affect the ride much unless it’s full. The experience of riding it, like any first-generation G/S, offers a peek into the past and what was the future.

The riding position is upright and comfortable, but tall and commanding. Just swinging a leg over, it’s reminiscent of plenty of late-model “tall-rounder” machines — Yamaha Tracers, Triumph Tigers, etc. — and of course there’s an obvious reason for that. High footpegs are the only real oddity when comparing this first-gen G/S to any number of modern bikes. There wasn’t any way to know it in 1980, but it’s particularly interesting in the context of the OG G/S that this half-and-half posture would come to be almost the norm.

Starting the engine and dropping the bike into gear is to go from 1980’s future to 1980’s past. For anyone who has ridden a BMW twin built between 1960 and 1975, that’s the feeling — a calm and slow idle, with plenty of noise from the valves and intake when it revs. The transmission is a little clunky and if a rider isn’t used to it there’s a learning curve to knowing when a gear is engaged and when the tranny is in no-man’s land. Also, once you get going don’t expect that front brake to work very well. Discs were still kind of new, people.

Provided you’re deliberate with your shifting and don’t expect vicious acceleration or deceleration, an old G/S is a delight to ride. Especially buzzing along the rural Vermont roads surrounding this bike’s nest, where twisty ribbons of pavement with 50 mph speed limits dictate an ideal pace. The chassis isn’t as stable or as agile as a modern bike, but it’s balanced and fun. It’s easy and pleasant to settle into the top gear of the five-speed gearbox and let the 45-ish horsepower drone along, peeling over from side to side as tall grass and wooded hills whip past. It’ll go 80 all day, with a fair amount of applause from the valvetrain.

Sometimes in Vermont, and in the world, the pavement simply ends. And almost no matter what road follows — miles of loose stones and washboard, ruts and greasy mud, or a smooth belt of mostly hard-packed gravel — the G/S will continue to shine. Depending on the road, it clatters and bounces like an old pickup truck but, just like an old pickup, it seems right at home. When you get to the limits of capability the wide handlebar and big front wheel make you feel like you’re in control, even if that’s not true.

Eventually, the going will get too rough or too deep, too muddy or too sandy, and where a dirt bike or even a modern ADV might thrive the ol’ G/S will be in over its head. It’s easy to shrug it off, but don’t forget that for BMW Motorrad in 1979 the idea of burying one of its bikes on a muddy trail or even thinking about jumping it was borderline insane. We’re almost numb to the concept now, having seen photos ad nauseum of every Tom, Dick, and Helge with their GS loaded into a dugout canoe or upside down in a Sudanese sand dune.

The forest for the trees

It’s a legend for a reason, but the true genius of the GS’s rise to two-wheeled stardom is a blend of marketing and capability. While the optics of having a bike that can be ridden around the world are attractive, it’s too cynical to say that’s the only reason people buy them. GSs, then and now, have a different feel than a “regular” motorcycle without the tires ever touching dirt. Like sprinkling brownies with a bit of sea salt, the act of adding that whiff of off-road to the recipe made the G/S’s flavor come alive. A special street bike, different from the others.

I love riding my dad’s bike around my hometown, for some predictably sentimental reasons. It represents some distant stability for me, having been through wins and losses in my life, graduations and divorce, storms literal and figurative. After riding on the back for years I eventually took the keys myself. I tipped it over and I picked it up. Often it picked me up without anyone falling over, as motorcycles have the power to do.

Beyond that, I appreciate reflecting on what the machine holds for motorcycling, being an illustration of both history and of progress, something we can all point and understand for its impact. Maybe our editor is esteemed for a reason — there’s no such thing as a small ride on a bike like this.