We all have "if I won the Lotto" dreams — a new bike every week, a years-long round-the-world ride, a MotoGP team. Mine is giving up the fast-paced, glamorous (hah!) life of a motojournalist, moving to a small town in a great riding area, and opening a coffee shop/motorcycle museum where riders could stop for a caffeine fix and enjoy my collection composed exclusively of race bikes.

Why only race bikes? First, many are either created as one-offs or modified within minutes of coming out of the crate, so original and near-original ones are very rare, the unicorns of the sport.

Second, you might find everything you need to restore a 1970 Kawasaki H-1 on eBay. But if you're working on a Kawasaki H-1R roadracer of the same year, you might have to look a lot harder, or even make some parts yourself. The effort and persistence add to the appeal.

Third, you can't see where you're going without looking back to where you've been. Race bikes represent the extremes of motorcycle engineering as it existed at the time and foreshadow technology to come. In that sense they're also time machines.

The 35th Annual Mecum Vintage and Antique Motorcycle Auction in Las Vegas, coming up next week, has dozens of candidates for my museum. Here are five bikes I'd spend my Lotto winnings on, as well as alternates in the unlikely case I got outbid.

1968 Harley-Davidson KRTT

Harley-Davidson's XR750, in both flat-track and roadrace variants, is a popular classic racer but not especially rare. Harder to find are earlier factory racers like this 1968 KRTT.

In the year the KRTT was made, AMA racing rules limited overhead-valve engines to 500 cc but permitted 750 cc side-valve engines like this KR. The British factories put pressure on the AMA and in 1969 the rules were changed to allow everyone 750 cc, regardless of valve layout. Now outclassed, the KR soldiered on, but the writing was on the wall and H-D dusted off the drawing board.

An all-iron Sportster-based engine proved a failure, but the subsequent all-aluminum XR750 became the winningest engine in AMA history. The KRTT was the last gasp of the side-valve era, and earns its place in my museum by dint of its 16 years as the most dominant tractor engine in American racing.

Second choice: Still, I wouldn't sneer at an XRTT 750, not even a replica like this one. I've never forgotten watching Cal Rayborn wrestle one around Laguna Seca in 1972, scoring both his and H-D's last AMA National roadracing win.

1969 Yamaha TR2

Yamaha’s two-stroke, twin-cylinder production roadracers gave many a talented rider — and many a talentless one, like me — their first taste of a real GP bike. The early 250 cc offerings were Tinkertoy-fragile bottle rockets with razor-thin powerbands and short fuses. Some guys went fast on them, but not for long between rebuilds. The 1969 TR2 changed all that.

The company's first production 350 racer, the air-cooled TR2 had horizontally split crankcases that made engine service easier. Its featherbed-type double-cradle frame had genuine racing ancestry, and its huge four-leading-shoe front brake performed its duties in a reliably brake-like manner. The fork and shocks, too, were racing spec, not repurposed street parts.

With claimed horsepower equal to Harley's 750 cc KRTT, the diminutive TR2 sent tremors through the four-stroke ranks. But it wasn't until the R2-based engine gave way to the R5-based TR3 that the phrase "giant killer" became practically a Yamaha trademark. The lesser-known TR2 slew its share of giants, too, but because it's largely forgotten now, there's a place in my moto-museum for one.

Second choice: This 1978 water-cooled Yamaha TZ250E isn't the TZ I really want — that would be a 1974 TZ250A, one of which I raced — but the E model will do. I couldn't fit on that tiny seat now without major modifications to the bike or myself, but I'd be happy to look at it all day.

2006 Harley-Davidson VRSC Destroyer

You don’t have to look very closely at Harley-Davidson's corporate DNA to see its racing gene. It's the one just sitting there vibrating like a guitar string. Over the years, it has spawned flat-track bikes and roadracers, and in 2006 it gave the world Milwaukee's first production dragster, the VRSC Destroyer.

Built to run in AHDRA (All-Harley Drag Racing Association) and NHRA Pro Stock events, the Destroyer came out of H-D's Custom Vehicle Operations (CVO) department. Powered by a 60-degree, liquid-cooled, four-valve-per-cylinder Revolution engine bursting with Screamin' Eagle goodies, it had a claimed 165 horsepower and the ability to run sub-10-second quarter miles at 144 mph.

Harley planned to build only 150 of the $30,000 Destroyers, but pre-delivery hype and the resulting attention eventually brought that number to 646. A fair number of them never saw a race track, their owners seeing them instead as investments. The Mecum listing doesn't say if this one was ever raced, so there's a chance it's as original as it was the day it was uncrated. With the wheelie bar installed, it's as long as two or three regular bikes, but I'm sure I could manage to find an extra-long velvet rope to go around it.

Second choice: For a track longer than a quarter-mile, my eyes were drawn to this 2000 Hayabusa land speed racer, which has definitely been raced, in this case by the late Bill Warner to a record 278.6 mph.

1957 Mondial Grand Prix "Dustbin"

If you think aerodynamics in motorcycle racing is a recent innovation, you're in for a shock. In the 1950s, factories tried everything to wring more speed out of their bikes, including so-called "dustbin" fairings, like the one adorning this 1957 Mondial Grand Prix.

Under that gorgeous fairing is a DOHC 125 cc four-stroke single with a four-speed gearbox. This is no replica, but the result of a years-long restoration by Giancarlo Morbidelli. In its heyday, riders like Sammy Miller and Cecil Sandford tucked in behind the swoopy nose; the two scored fourth and sixth respectively in the 1957 125 cc World Championship.

Fairings like this one were eventually banned from racing because of their effect on braking and their behavior in crosswinds. There would be no wind of any kind inside my museum, so the Mondial could be displayed with its swoopy clothes intact.

Second choice: Boasting the absolute minimum of everything it needs to qualify as a motorcycle, this 1961 350 cc AJS 7R "Boy Racer" appeals to the minimalist in me. Sometimes less is more, and this is one of those times.

1982 Kawasaki KR500

I have a soft spot for bikes in the "nice try" category. The KR500 was built to challenge Yamaha and Honda in the 500 cc Grand Prix series. It had all the right stuff, like a square-four, rotary-valve, two-stroke engine and a monocoque frame, but success eluded it.

By all accounts, it was as exhausting to tune as it was to ride. Complexity is fine if it works, but there's such a thing as too many choices, and the KR's extreme degree of adjustability, compounded by a lack of testing time, might have hurt more than it helped.

By the 1982 season, the bike was competitive, with rider Kork Ballington scoring nine top-10 finishes and ninth in the World Championship. But Kawasaki had had enough and pulled out of GP racing at the end of the year. My own racing career was unblemished by success, so I forgive the KR500 and invite it to a podium in my museum.

This bike for sale in the auction is a carefully built replica of Ballington's race bike.

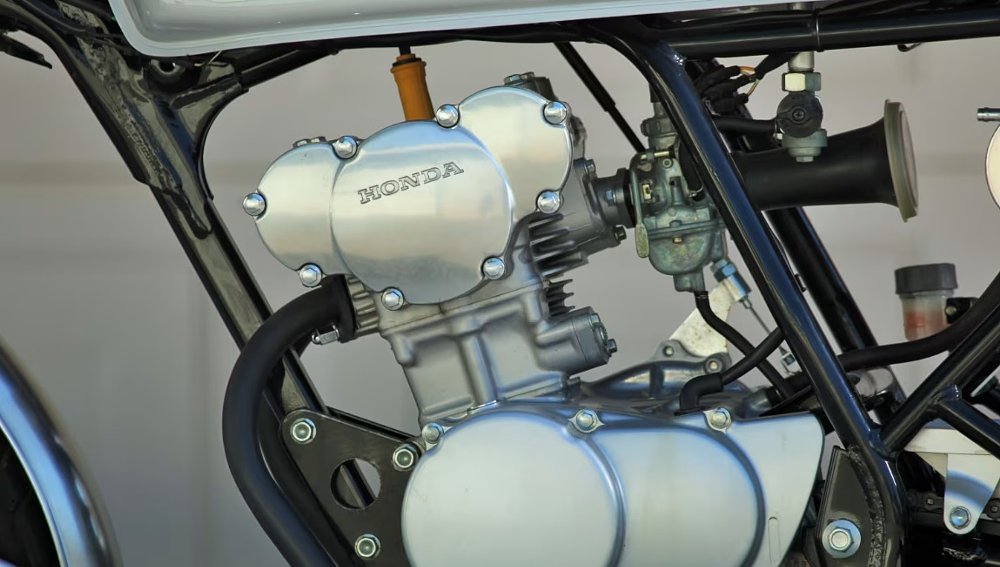

Second choice: This 1981 Honda RS600 flat-tracker, built by AMA Hall of Fame rider Ronnie Jones, is the epitome of what I love about flat-track bikes — simple, unadorned with extraneous tech, and as deadly serious as a straight razor. I'd park it on a thin layer of dirt in my museum and surround it with haybales.