When I was a kid, I used to pedal my Huffy down to the local airport’s restaurant to watch air-cooled BMWs ride in for their Saturday club breakfasts.

A long line of shiny Beemers would be parked handlebar to handlebar, clinking and ticking as their engines cooled, while riders in tall leather boots and color-matched helmets wandered into the restaurant for coffee. I didn’t know what a boxer engine or an airhead was back then. I just knew those bikes were BMWs, and from the way they looked and sounded, I figured they had to be the coolest motorcycles on the road.

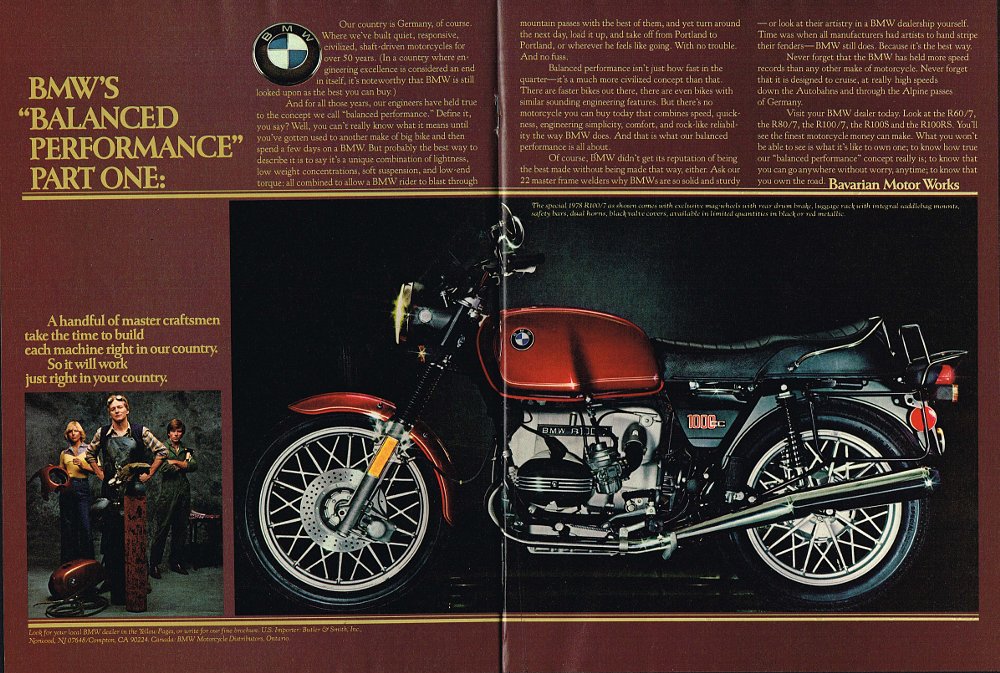

I’ve seriously considered buying a classic BMW of my own several times, never quite finding the right one, but a trip to the Nettesheim Museum in Long Island last year kicked that desire into overdrive. That article led to an offer I couldn’t refuse from one of Common Tread’s most dedicated readers, Mr. J. Leet. His 1977 R100/7 was in for service when last September’s flooding swept through the northeastern United States, and the deluge swamped both the shop and the motorcycle in brown murky water.

The tough ol’ boxer still ran after its swim, though it would need some work for a full return to its former glory. I was offered a sale price of less than a thousand dollars so that the bike would qualify for the Reliability Rally, a two-day, 500-mile cheap bike challenge that I completed last year on a junkyard Kawasaki Ninja 500. How could I turn down a deal like that? The R100/7 soon rolled into Greaser's No Kill Motorcycle Shelter for repairs. The bike would stay as close to stock trim as possible except for anywhere I could use a respected aftermarket fix in place of a problematic original part.

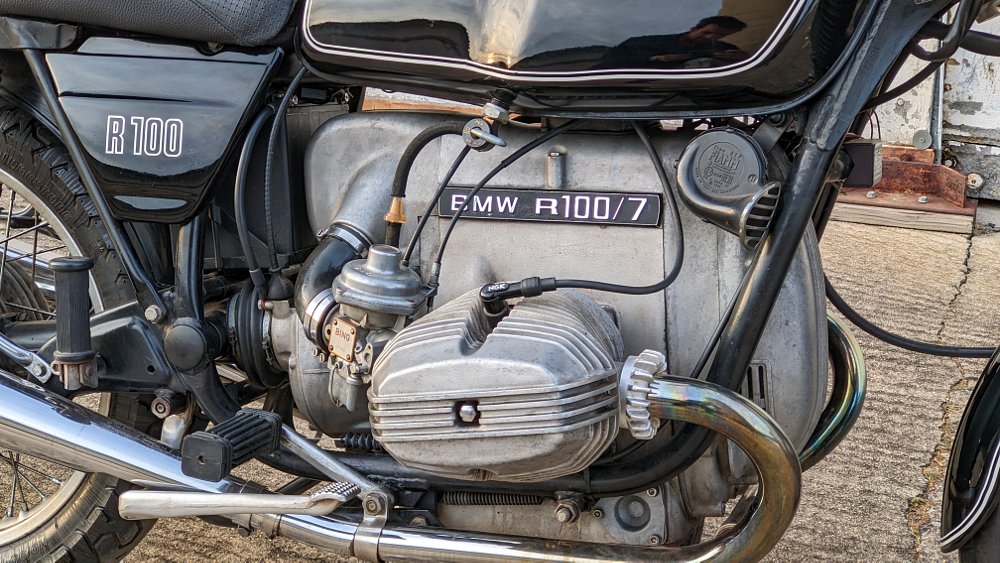

This R100 dates back to the introduction of 980 cc airheads under the /7 series, the largest air-cooled boxers BMW ever stuffed into production motorcycles. My new purchase turned out to be a perfect first step into classic BMWs with massive aftermarket support and a community full of knowledgeable — and opinionated — owners to guide my bike’s rehabilitation. After several nights of scrubbing, it was time to dig below the surface of the R100/7, checking major service items and correcting any problems I found along the way. I reset the trip meter to track my progress and started wrenching. The rally was just a few months away, and my only ride so far had been getting the bike onto my trailer.

Trip meter: 0000

The bike's oil was flushed and a new battery installed after the flooding incident, so I checked my T-CLOCS items and took the Beemer for a quick test ride. The last of the flood water blew out the tailpipes in a cloud. Ker-chonk, that’d be first gear, and the R100/7 was briefly back on the road. (This would begin a long process of test riding, discovering issues, solving those problems, and further test riding to start the process over again.)

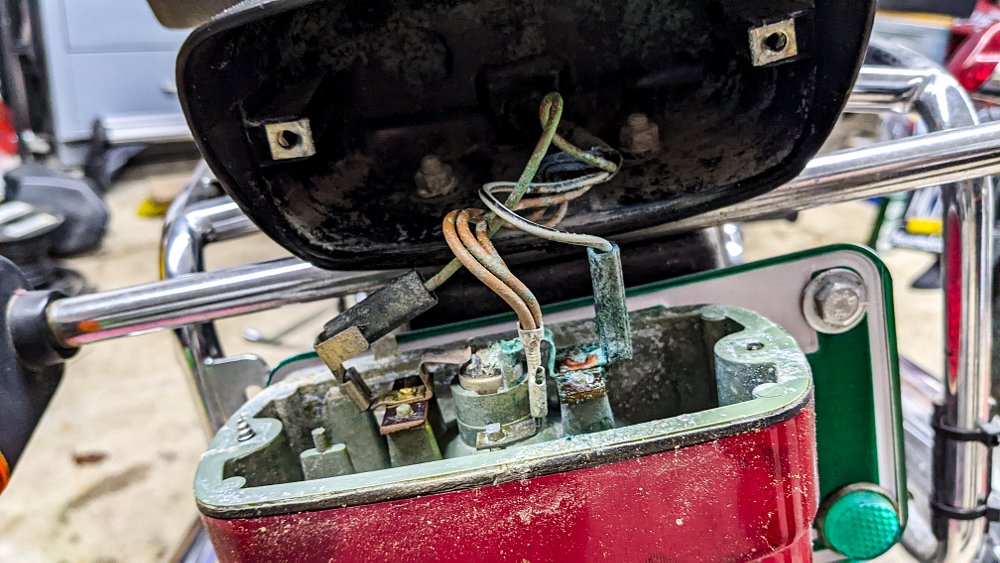

As character goes, the R100/7 is a strong cup of coffee. It thumps and whirrs and shivers at idle, then surges ahead with a torque hit and unmistakable exhaust note on acceleration. The low center of gravity gives excellent handling for its era. The years had not been kind to the bike’s electrical system, unfortunately, and the filthy water must have pushed some components over the edge. The first issue I discovered was a dead battery when I went to take the bike out for a second ride. The problem was traced to a shorted out starter relay that was hot to the touch.

The headlight relay had also conked out, and as I disassembled the headlight bucket to access it, I discovered that the “high water mark” had been halfway up the headlight. Poor motorcycle. A sloshing sound at the front end turned out to be fork gaiters full of water.

Trip meter: 0022

Soon, I was learning my way around the forums and popular parts suppliers for these old gems. I also picked up reference materials like Rick Jones’ Classic BMW Boxer Charging, an R100/7 owner’s manual, and the Clymer airhead manual. Much of the wiring harness was corroded and suspicious. Slowly, carefully, I worked my way through the electrical system.

The starter relay swap revealed a failed regulator, which led to a complete battery cable replacement, which led to a new Valeo starter to replace the rusted-out Bosch, which led to a Thunderchild diode board with solid mounts and a new charging system from EuroMotoElectrics. Articles and videos from BMW sages like Snowbum, Anton Largiader, Brook Reams, and William from Boxer2Valve guided me through the Beemer’s electrical refresh. My multimeter hasn’t seen this much use in a while.

Now that the electrical system was behaving, I didn’t have to bump-start the bike every time I turned it off. I decided to change the engine oil and filter myself just to be sure that all of the water was out of the engine. This job can be intimidating because of the infamous "$2,000 O-ring" on the oil filter housing. No, this innocent-looking white O-ring doesn't cost two grand to purchase. But installing the O-ring incorrectly, or even re-using an old one, can allow oil to escape the oil filter assembly, eventually starving the engine of oil and causing serious damage that would cost around $2,000 to repair. The "$2,000 O-ring" nickname has been around for a long time, and the actual cost of repairs today would surely be much higher. Careful measurement of shims pressing on the O-ring ensures a good seal. I've never used a micrometer or algebra to change my oil before.

I also flushed fluids in the transmission, driveshaft, and final drive. The steering and wheel bearings felt fine, so I gave them some grease and put them back to work. Eventually I’ll replace them just to be sure. Listen to me, I’m already sounding like a BMW guy…

I rebuilt the front brake system with a new piston and seal kit, a new hose, and some fresh fluid. This R100/7 is a single-disc model with BMW’s unorthodox cable-actuated hydraulic system. Pulling the brake lever moves a cable that swings a lever to push the master cylinder’s piston. The master cylinder is mounted under the tank along with the reservoir. Later versions used a more conventional setup with the master/reservoir out on the handlebar. I wouldn’t mind a dual-disc Brembo fork from another model, but the ATE single-caliper system works well enough once rebuilt and properly bled.

Trip meter: 0035

My airhead started running like garbage after some additional electrical work. It couldn’t idle, coughed a lot, and felt severely down on power. Almost like it’s running on one cylinder… Further inspection revealed that one of the spark plug leads wasn’t fully plugged into its coil. This was easy to fix because I’ve never had a motorcycle with such an easy tank removal process. It’s totally toolless. Undo two thumbscrews in the back that clamp it to the frame, pull off the fuel lines, and lift it out. Genius. With the tank out of the way, the wire could be pushed back into place, and the R100’s lazy idle returned to normal. I once heard a story of an airhead rider traveling across several states on one cylinder after removing the remains of a broken valve. I hope I don’t need to use this information during the Reliability Rally.

By this point, I was learning how to look for answers to my BMW questions. These motorcycles are not like the Japanese bikes that usually fill my garage. On a Beemer, almost everything has an adjustment, a torque value, a special tool, and/or a civil war on a forum somewhere about the correct procedure for the job at hand. Don't buy an airhead if you hate research.

Around this time, I heard about Daren Dorton's Airhead 247 podcast. Notable guests from the vintage BMW world come on the show every two weeks to tell stories, give tech tips, and offer their opinions on every facet of these motorcycles. Good stuff, and available on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, Soundcloud, and a few more services.

Trip meter: 0058

Next on the checklist was the all-important valve service. I learned to find the timing mark on the flywheel by pulling the bike up on its center stand (among the easiest I’ve ever used) and turning the rear wheel in fifth to move a piston into top dead center on the compression stroke. Removing the valve covers was a snap, but the right cover revealed that a rocker shaft bearing cage had failed on the intake side, dropping all of its needles and causing excessive noise on that side. Not great.

Some research suggested that rocker bearings from my R100/7’s era are known to fail in this way, so I removed all four rockers and preemptively replaced all the bearings before finishing off the valve clearance adjustment. The intake valve rocker shaft was also replaced, just in case. I put an inspection camera down the spark plug holes on both cylinders to check for signs of damage. Everything looked fine, and the valvetrain sounded much happier on my next test ride.

Trip meter: 0088

Replacement clutch and front brake cables were delivered, installed, and adjusted. What an improvement! The throttle cables I ordered were too short, unfortunately, but I could tell that the ones on the bike were relatively new. A shot of cable lube and a quick inspection were the least I could do. Reliability Rally founders Colin Gorey and Lou Turicik advise that snapped cables are the number one culprit of DNFs in their event.

While I was working on the throttle, I had my first in-person look at BMW’s Rube Goldberg throttle mechanism. The throttle tube is ringed with gear teeth inboard of the grip, which turns another beveled gear, which is connected to a short length of chain, which terminates in a block with slots for each of the two throttle cables. Once cleaned and lubricated, the system works nicely. There’s even a tension screw, externally mounted, that can add some “cruise control” effect for highway riding. The contrast between the BMW throttle system and the typical designs you’ll find on classic motorcycles makes a good example of what sets these motorcycles apart. They’re somehow both complex and simple at the same time.

Trip meter: 0144

The front suspension hadn’t felt right since I checked the wheel bearings. It kept binding, clacking, and making bubbling sounds from the top of the fork. A little research suggested that I should have tightened down all the front suspension fasteners with the front wheel on the ground, not up in the air on the center stand. The fender mount, axle, and aftermarket steering brace needed a few bounces of the fork to find their happy places before tightening. This technique, plus a fork fluid change to Motul Synthetic 7.5 weight, solved most of the binding and clanking. (I suspect there’s a bushing that still needs attention.) What about the bizarre hissing and fizzing sounds? A seal under a fork cap had split apart, and a new one hushed the leak.

A fiberglass underseat tool tray showed up in the mail, along with a complete OE tool kit, and an official BMW rag (p/n: 71119090188) that makes me laugh every time I see it. I immediately wiped my oily hands on the rag to break it in.

Trip meter: 0228

I took the R100/7 out for a longer ride with more confidence in its overall state of tune. The bike felt transformed: smoother, faster, and more responsive than ever. The only things left on my to-do list were minor items like replacing the fuel lines, adding new rubber intake connections, and final adjustments to the throttle.

I wish that I had the chance to rack up more miles before the rally this weekend, but diagnosing problems, waiting on parts, researching the correct fixes, and repairing everything by myself took time. It also taught me some basic airhead troubleshooting skills that will probably come in handy someday.

Meeting your heroes

Is owning an airhead as cool as I thought it’d be when I was a kid? I think so. I’m sure it would be wunderbar to buy a nice clean example with full maintenance records and no submarining in its history. That doesn’t fit the ethos of the Reliability Rally, though, and spending top dollar on perfect motorcycles isn’t my style, either.

Wrenching on the R100/7 showed me the care and quality that went into the bike when it was built in Munich, West Germany. Advanced work should be done in the comfort of a well furnished home workshop with a few special tools, but routine maintenance items are easy to access and adjust at any time with the onboard tool kit. I suspect that once an airhead is in good running order, it is not terribly difficult to keep it that way. (Avoid floods if possible.)

Riding the R100/7 is a rewarding experience after all those hours in the garage. I don’t know a motorcycle that’s quite like an old airhead. For better or worse, BMW did things their own way, with little adherence to anyone’s tradition but their own. In other words, the R100/7 isn’t trying to be anything other than the logical advancement of its ancestors. It feels refined, sturdy, and eager. What would it have been like to buy one brand new in 1977? Then, as now, a big BMW promised grand travels and the best motorcycle engineering Germany could offer. I get the appeal.

The R100/7 was, and is, a fine choice for seeing the world. If the bike survives the Reliability Rally, I’ll take care of a few more maintenance items, then that trip meter will really start spinning. And if I break down? At least I’ll have enough knowledge and tools with me to figure out just how bad the trouble might be. Look for a Reliability Rally ride report in the next few weeks. We’ll see if my mechanical abilities saved this motorcycle or set me up for a breakdown.

Special thanks to Colin, Lou, and the Reliability Rally team for the event, Daren Dorton for the very helpful podcast, and Peter Nettesheim for convincing me I needed an airhead. Thanks also to the many airhead experts who freely share their knowledge through articles, photos, and videos across the web. And the biggest thanks of all to Mr. J. Leet for the opportunity to save this motorcycle.