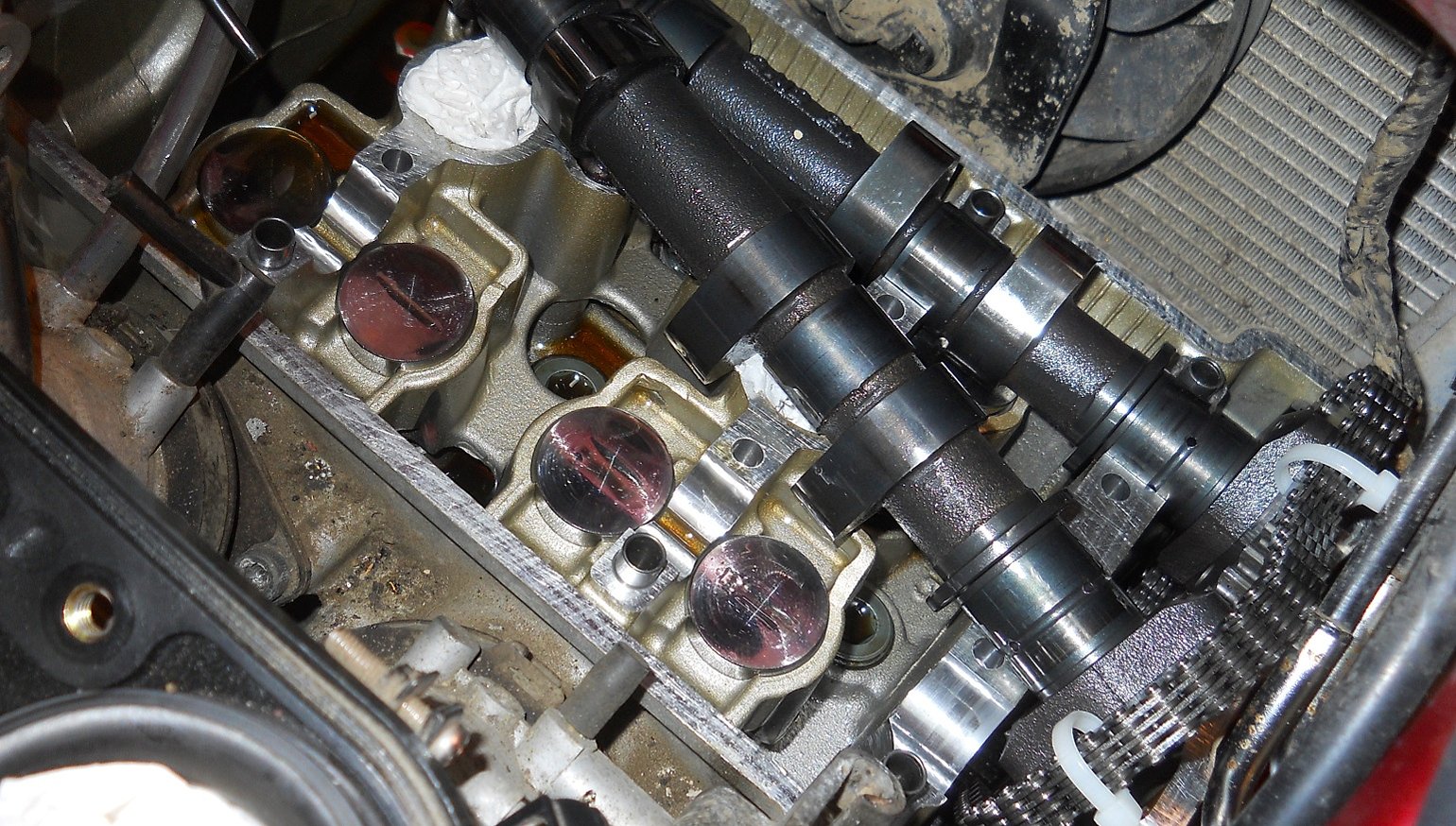

I'm just about to pull the cams out of my Kawasaki Ninja 650 and replace six of the eight shims to bring those valves back to spec. It's taken me a couple of weeks to dig down to the valve cover, after removing the tank, the airbox, the throttle cables, a rat's nest of hoses and breather tubes, and half a dozen wiring junctions, each of which has inexplicably welded itself into a solid piece, as inseparable as it is brittle.

That I've taken so long to do what a competent line mechanic can do in an afternoon reflects not only the sorry state of my knees and an arthritic spine ill-disposed to bending, but also a reluctance to meddle with mechanical things that stems from my earliest encounters with broken, maladjusted, or eccentrically built motorcycles. I can hardly pick up a wrench without experiencing flashbacks to some DIY disaster or other in my past, starting at the beginning and leading right up to the present.

An uneasy relationship with maintenance and other DIY disasters

The first of these traumas took place in my own garage while trying to adjust the shift lever on my very first bike, a Kawasaki F3 Bushwacker. The set-up kid at McCoy Motors had positioned the shift lever such that no actual human could operate it easily. I loosened the pinch bolt and gave the lever a tug, at which point the entire shift shaft — lever still attached — slid out of the crankcase and into my hand. A tiny circlip on the other end of the shaft was all that held it in the engine, and that circlip, along with the shift selector it also retained, had fallen into the depths of the engine.

With the help of a sketchy shop manual written in fractured English, some of the tools my father had used to work on bombers during World War II, and the cheesy wrenches and screwdrivers in the stock tool kit, I managed to remove the carb, the rotary valve, and the clutch cover, fish the missing parts out of the crankcase, and put it all back together. My sense of accomplishment was short-lived because a month later I once again pulled the shaft out while trying to reposition the shift lever.

After I began roadracing my Yamaha R5 in the AFM I hooked up with a local tuner who I'm now certain looked at me and saw a guinea pig who slept in a nest made of money. I essentially paid him to test his theories on my bike, but with little understanding of what he had done it was left to me to jet the carbs and adjust the ignition on the day of each race.

One weekend, while changing the main jets, I pulled the carbs off the bike, leaving the slides dangling from the throttle cables. After I put them back the bike wouldn't idle or accelerate. I spluttered up and down pit lane for an hour trying to figure out what was wrong when someone suggested I might have put one or both of the slides in backwards.

Affronted, I insisted I hadn't, and then after a while, when nobody was looking, I checked the slides and… you know the rest. My joy was once again short-lived as the jets I had put in the carbs caused the engine to seize up solid on the third lap of the race.

I've written about my Ducati Darmah SS many times, and each time I've questioned the parentage and legitimacy of whoever thought desmo valves were still a good idea by the late 1970s. For a time, I parked the bike at the home of a friend who lived in a condo. There, I did all my own work on it, including shimming the valves at ludicrously frequent intervals. More than once a neighbor tactfully suggested to my friend that he might have a word with the angry man who was always lying under the pretty blue motorcycle in the downstairs garage swearing at it like a drunken sailor.

Fortunately, motorcycles became more and more reliable as I grew less and less inclined to work on them. But there were times when I had little alternative to rolling up my sleeves, such as when I took my V-Strom to the Suzuki shop for an estimate on adjusting the valves. The mechanic — or, more accurately, "mechanic" — was a pimply kid in a T-shirt emblazoned with the name of some heavy-metal band. The gloves I had worn on the ride over were older than he was. I asked if he'd ever adjusted the valves on a V-Strom and he said, "I have a CBR600 Honda. It’s pretty much the same, right?" In a very broad sense, it was, but I wasn't convinced it was quite enough the same thing, so I decided to do the job myself.

I'd had a good relationship with the V-Strom up to that point. My affection for it was tested as I delved into its innards. By the time I drew the shims out of the buckets with a magnet, we were barely on speaking terms. I began to long for my two-stroke days, when only four bolts held on the entire top end of the engine and I could put in new piston rings before the cup of coffee on the workbench cooled.

My unwillingness to work on bikes, and my reluctance to pay someone else to do it, has influenced a number of bike purchases. Even now, when I see a Honda CB750 Nighthawk for sale, my first thought is "It has hydraulic valves! I should buy it!" My Ninja is an anomaly. Were it not for the great deal I got on it, I probably wouldn't have considered inviting it into my life, especially knowing that at the time of sale the bike had 36,000 miles on it and had never had the valves checked. But the worst is almost over. With 40,000 miles on the clock now, I’m comforted by the notion that after I shim the valves and replace all the stuff that had to come off just to get at them, I’ll probably never have to do it again.

Just in case, however, I'm putting away a few bucks every week against the day — and that day is coming fast — when I'll grit my teeth and pay a teenage metalhead to do what I no longer want to do.