When I step into a motorcycle shop, the first thing I want to see is the owner’s bike.

I don’t care about the showroom filled with custom bikes, their latest T-shirt design or pictures from that magazine shoot 10 years ago. I want to see that daily rider parked out back. I’ve found that you can learn a lot about a person just by seeing what he rides and wrenches on, especially if he is in the motorcycle industry.

When I caught a glimpse of one of Andrew Johnson’s personal machines, I could tell right away that he was a lot more than just your average bike builder and I had to learn more. Andrew owns Antique Speed and Machine up in Valatie, N.Y., and the machines he builds are not what the engineers at Harley-Davidson intended — but maybe what they should have.

In case the chain-wrapped rear tire didn’t tip you off, Andrew’s latest build is a hillclimber. Hillclimb racing dates back to the 1900s, when it was popular enough to attract the best racers. Andrew built this bike just to see what it was like to ride one of those early race bikes. Just like all forms of racing, specialty machines were developed to go faster and farther than their stock counterparts, and Andrew’s machine uses many of those old-school tricks to make it as true to the racers of the 1920s and 1930s as possible.

Starting with a single-downtube WL frame, Andrew stretched the rear triangle four inches and then added a third bar for additional support. Harley-Davidson actually produced some “three bar” frames specifically for hillclimbers, but those are rarer than hen’s teeth and the only practical way to get one is to build your own. This design was used to shift the weight of the engine farther forward, which helps keep the bike from rolling over on the steep inclines that hillclimbing is known for.

Andrew also modified a beefy RL springer front end to handle the bumps on the way uphill. Only built in the 1930s, the RL springer uses a forged I-beam rear leg, making it one of the strongest front ends Harley has ever produced. Later springers switched to a hollow rear leg that was weaker, but cheaper to manufacture.

The drivetrain on this machine is where Andrew really pulled out all the stops. The motor is all Harley, but is comprised of a WL bottom end and an Ironhead Sportster top end. For those who know a thing or two about Harley motors, this may sound a bit confusing, because the WL motor uses a sidevalve configuration and the Sportster uses an overhead valve configuration. Needless to say, this is not your average bolt-together aftermarket upgrade! In racing circles, this setup is known as the Magnum 45 and it takes a true machinist to build one.

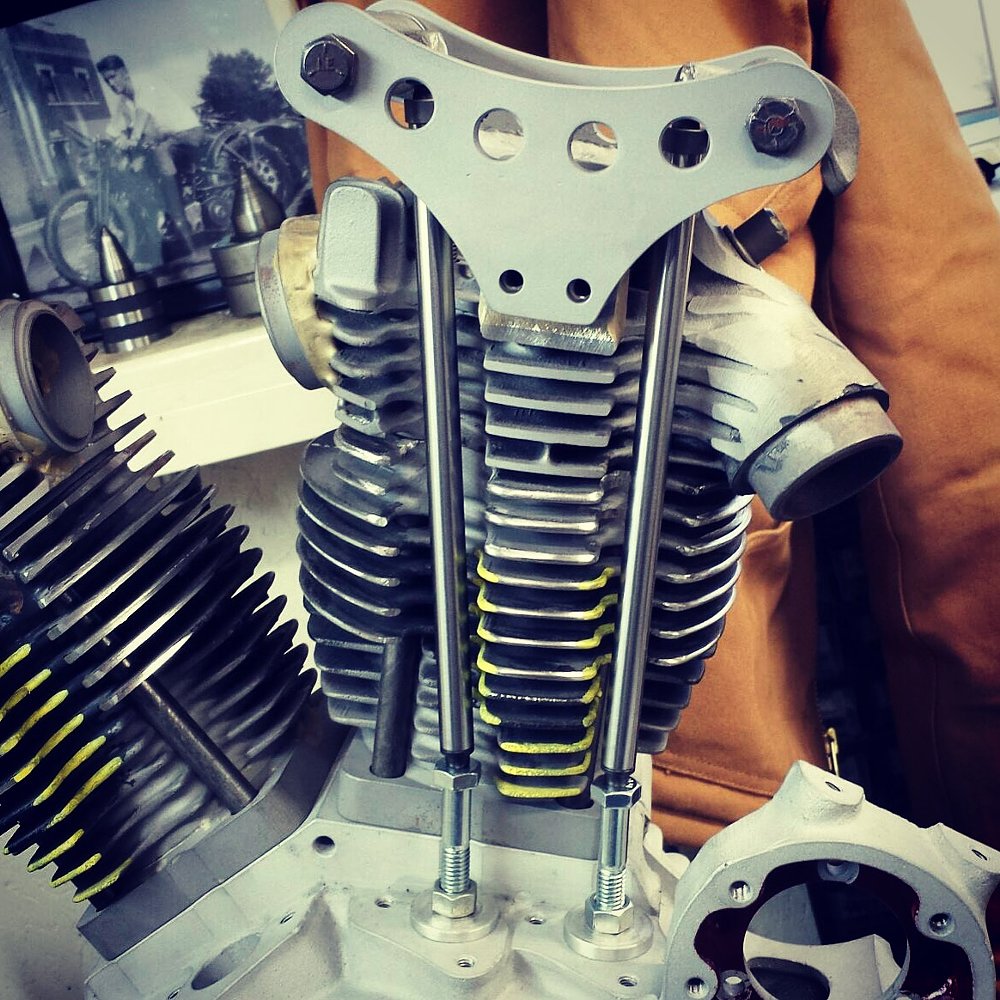

As you have probably guessed, parts from dissimilar motors don’t just line up, so the first major hurdle was attaching the cylinders to the cases. To correct the misalignment, Andrew first welded up the stock bolt holes in the WL cases and then rebored them to match the Sportster bolt pattern. It’s important to note that both the WL and the early Sportsters use short studs to connect the base of the cylinder to the cases and then separate headbolts to connect the heads to the cylinder. Harley updated this design decades ago and they now uses a single set of long studs, which go all the way through the heads and cylinders, making for a much stronger design. Andrew agreed with Harley’s engineers on this account and decided to modify his cylinders and heads to allow for the long stud arrangement.

One of the easiest ways to tell the difference between a sidevalve and an OHV Harley motor is by looking at the position of the carburetor. The carburetor is mounted on the left on a sidevalve and on the right on OHVs. As a nod to the stock flathead design, Andrew also decided that the carburetor should mount on the left side of his hillclimber. This required cutting the stock intake ports out of the Sportster heads and replacing them with custom-made intake ports facing the opposite way. As a final touch, he also built a set of external rocker supports that leaves the entire valve train exposed, so you can literally see how everything works while the motor is running.

So far, Andrew has been enjoying the hillclimber on flat surfaces, but he has plans to head up some steeper slopes in the near future. After putting so many long hours into building this amazing custom machine, he doesn’t want to risk wrecking it just yet. When he does make it to his first event, I assure you there will be more than a couple folks scratching their heads trying to figure out where that powerplant came from.

The Magnum 45 is hands down the coolest motor that Harley-Davidson never made and puts this machine in a category all its own.