If any of you happened upon my Conserve The Ride article, you will have read that my stupid dirt bike nearly ran out of lubricating oil due to a little failure of some of the electronic bits.

How to perform a dry compression test

- Disable fuel supply to the engine

- Disable ignition system

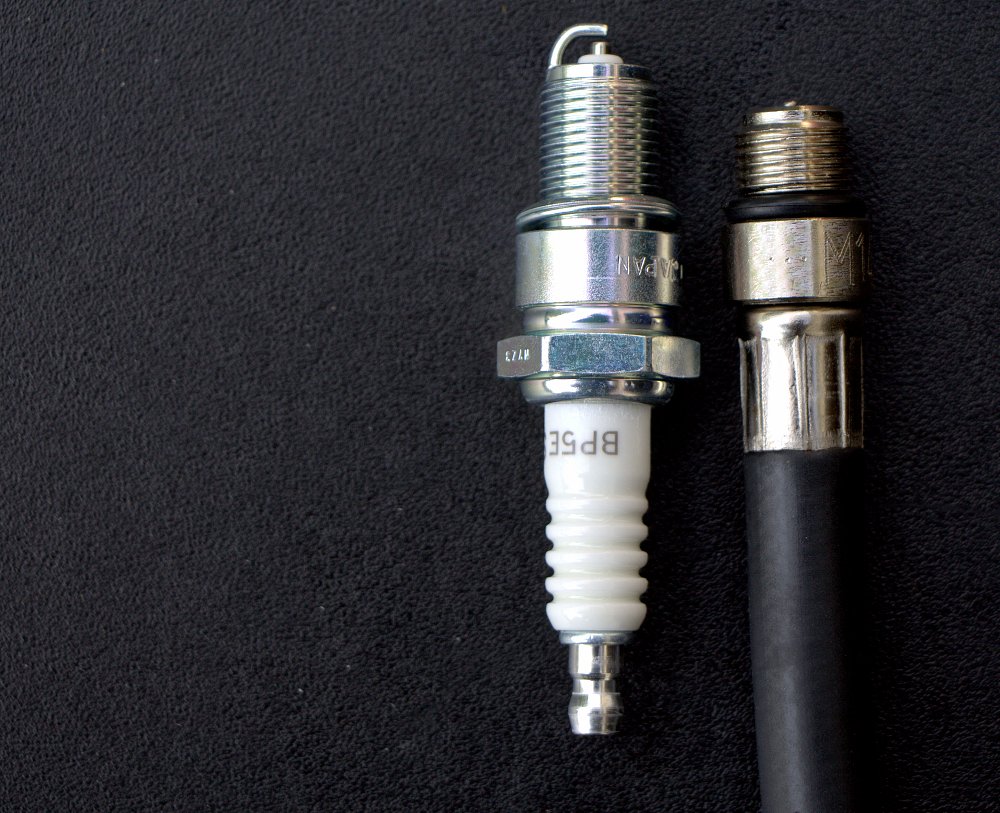

- Remove spark plug

- Install compression tester

- Open the throttle completely

- Turn engine over with starter

- Record highest number achieved and compare with factory specification

- Repeat for each cylinder

- Compare readings from cylinders and be sure numbers do not vary from one another beyond factory specification

- Perform a wet compression test and leakdown test in that order if warranted

There’s more to that story. I wasn’t sure something wasn’t damaged. Sure, I put two-stroke oil in the tank (and the injection tank!) immediately, but I didn’t know if I blew something up. I heard no weird noises and the bike never seized or shut off… but that’s no guarantee that all is right inside the engine.

I often say that mechanics are good with wrenches, not crystal balls. We usually use external clues to extrapolate what type of shape the insides might be in. I mean, that, or we just start ripping things apart and making you pay us.

However, when it comes to engine internals, we actually have a crystal ball. Or maybe X-ray vision. Something like that. There’s a test any mechanic worth his salt will perform, and that’s the compression test. Compression tests can tell you a little bit about what’s going on inside your cylinder. It tells about health of an engine, about sealing, and reveals problems your eyes can’t see. Most importantly: it saves teardown, and thus, your time or money.

To perform a compression test, you need… well, a compression tester. That’s mandatory. If you have any engines and you do even a little wrenching, you really should have one of these. (And you can get one from my favorite retailer. Just sayin'.) Other than that, though, all you need is some free time. Heck, if you just want to see the health of your engine for fun (if you're one of those nerdy engineering types) or your own peace of mind, you can always try a compression test without having a potentially broken motorcycle in front of you.

Oh. Wait. One more thing. A compression spec might be helpful. Back to my dirt bike. Normally, this is something that is listed, but my Beta “manual” (I’m being kind here; It’s literally a printed-out Microsoft Word document) didn’t have anything listed.

I called two Beta dealers. One said, “Oh, like 150 is good.” Yessir, I know that 150 psi is in the ballpark, but I’m trying not to tear down my engine here, and having a number would be helpful. If you’ve never performed this test, you should know that normally, acceptable compression values are given within a range, say something like “148-162 psi.” There’s also usually a stipulation that all cylinders test within a given percentage of one another, as well. Obviously this doesn’t matter on a single-cylinder dirt bike, but it is important. Needless to say, I was a little disconcerted to hear the next shop go 10 psi higher, too. “I’d want to see 160. Beta just says to replace the rings after 50 hours.” Great. Thanks.

Now, anyone who knows me knows that I’m a fan of doing things the right way — unless that ain’t possible, in which case good guesses and good intentions have to be substituted. So I sat down with my pencil and decided to see what I could calculate. My X-trainer has a compression ratio of 11.3:1. Lemmy Mountain sits about 1,000 feet above the sea, meaning my atmospheric pressure is 14.2 psi. Multiply those together, and we come up with 160.46. At least now we have a clustering of numbers.

I fired the bike up, and took it for a little rip. You’ll hear folks argue over performing these tests hot or cold. I like to test the bike how I ride the bike, and I’ve never ridden a cold motorcycle for very long. After that, I tore off some plastics, got out my compression tester, and performed my test. Unless you have multiple testers, you’ll be testing each cylinder independently, so I usually pull all the spark plugs out at once. (You want to do this so you’re not fighting the engine’s compression.) Screw your tester in, and lay it somewhere safe. (Most compression testers, even the cheapies, have a check valve to record highest maximum pressure attained. If yours does not, you want to put that tester somewhere you can see it while you’re spinning over the engine.)

At this stage, you should be set to fly. Disable your ignition and fuel systems so you don’t accidentally light something aflame, and open the throttle all the way up. This is important. Lots of people forget this. You don’t want your poor little starter trying to make those pistons suck in air on a closed throttle plate. You will get low readings, and then you will pull apart what might have been a still-good motor, and then you will be sad.

Now hit that starter button, and let the motor spin until the needle on the gauge stabilizes. (You need a strong battery to perform this test. If you don’t have one, get one. If you do have one, charge it between tests on each cylinder.)

I popped off 162 psi or so. Safe enough in my book. Note that on a multi-cylinder motorcycle, you'll test each cylinder, and your manufacturer may also have a spec relating to how far out each cylinder can deviate not just from their number, but from one another, too.

I put the bike back together, and resumed beating the shit out of it. Now you, too, know how to check compression. You should be aware that the compression check is a “quick and dirty” test. It gives you only a rough idea of what’s going on in the jugs; a mere snapshot of the goin's-on.

Alternative ending

“But Lem!” I can hear you now. “What if it was low?!” The shock! The horror! If it was low, I would have started tearing down the motor, because I'd know I'd have fried my rings, at very least. I would have looked at the scuffed piston as I pulled off the expansion chamber, said some bad words, and continued ripping the bike apart. It’s a 2T, which has a flat head and no valves. But let’s pretend this was a four-stroke, overhead-valve motorcycle. What next?

If we (Yeah, we. This fake bike belongs to both of us, so if it's really broken, I may make you do all the work on it.) had low compression, we’d have to figure out what was leaking. The next item of interest would be a wet compression test. We’d toss a teaspoon of clean motor oil into the cylinder, and then repeat the test. If the numbers suddenly increased, well, then we have bad piston rings on our hands. The oil slips between the ring and cylinder wall, and seals up the worn rings for long enough to significantly boost the number showing up on the compression gauge.

“And what if the number was still low?”

Glad you asked. Well, then the next thing we’d do is a leakdown test. Leakdown tests involve pressurizing the combustion chamber and cylinder, and quantifying that rate. Unlike a compression test, this test is static: the cylinder being tested is put at top dead center and held in place. Metered air at a given pressure is introduced, and the air’s escape (the leak) is quantified. Generally, less than 20 percent is considered acceptable, and under 10 percent is really good. A leakdown tester is a little more expensive than a compression tester, but I’d say not everyone should have one. If you know you’re not going to tear down and rebuild your engine, skip it. Your mechanic will have one, and he’ll want to see the numbers himself. The leakdown test tells no lies; it's not a snapshot of the internals, it tells you everything you can know without disassembling.

The neat part about this test is the escaping air’s destination generally tells us a little bit about what’s damaged in the engine. If the exhaust valve is sticking open, bent, or there is a problem with the valve seat (or seating!) the air can be heard hissing in the exhaust pipe. Similarly, if the intake valve is suffering from one of those maladies, our little imaginary four-stroke bike would be hissing from the carburetor. A crack in the head, block, or damaged head gasket often yields bubbles (or a geyser!) in the coolant. If you happened to perform a leakdown test before a compression test and you had air escaping the crankcase vent, you’d have bad rings.

I’ll leave you with a quick tip for you cheapskates out there. You can make an impromptu leakdown tester from your compression tester if you want to detect a gross leak. If your compression tester has airline disconnect fittings on there, yank the Schrader valve out of the spark plug fitting that corresponds to your head. Then hook it up to your air compressor, dial the pressure back to 100 psi or so, and open your ears. Gross leaks will, as mentioned, be audible.

Now you are sufficiently armed with enough information to be dangerous. What kind of shape is your engine in?