A good rider always knows what caused the crash. Really good riders know what happened before the crash has ended. Three months after I totalled a KTM 990 RC R while testing in Spain, I still don’t know what went wrong.

By the time my brain rebooted I was in downtown Seville, Spain, staring into a void of fluorescent light and listening to a gentle hum of activity that can only be described as “hospital.” I didn’t even know what turn I crashed in. All I had was a few blurry vignettes to remember that I had spent time flying through the air, then in a gravel trap next to a racetrack, and eventually in the back of an ambulance.

The whole thing would have been cemented in mystery but for two pieces of technology that documented the crash. A GoPro camera mounted to the top of the bike’s gas tank pointed forward, and the Alpinestars TechAir 7x airbag system I was wearing under my leathers. One shows the attitude and trajectory of the bike as I was thrown off, and the other tracked my body’s impact with the ground through the accelerometers built into the airbag system.

What the data says

From the video, I know I was in the middle of the right-handed Turn 10 at the Sevilla Circuit, in third gear, traveling at about 65 mph. I had the 990 RC R in Track riding mode, with traction control set to level 2 of 9. It was a stellar afternoon in the middle of Spain, with bright sunshine and a warm track. I could see former KTM pro racer Chris Fillmore up ahead, riding at about half pace and clearly slowing down from cutting fast laps. I did the same, relaxing from full attack in the preceding left-hand corner, sitting up a little and thumbing the horn to harass my friend.

The camera was recording at 60 frames per second, and by my count it took about 25 frames for the rear tire to start sliding and for the handlebars to get to full lock in the opposite direction. In other words, the bike’s electronics and I had less than half a second to correct the rear tire’s sudden loss of traction, and neither of us acted quickly enough. About 20 frames (or 0.33 seconds) after the bars went to full lock the bike snapped violently upright, with the rear suspension then unloading and slinging me into low orbit.

After that point, the motorcycle and I went separate ways and the video doesn’t tell me much about what happened to my body. However, I can see that there was enough force associated with the upward motion of the crash that the bike did nearly two full barrel rolls before the wheels slammed down on the track and the machine slid toward the gravel trap. That’s a serious charge of energy that the rear suspension and rear tire of the bike put into launching itself, and me, away from the ground. More rebound damping needed in the shock? Mmm, maybe.

One of the tiny slices of memory I have of this incident is feeling weightless in the air, like the top of a trampoline jump, and feeling a layer of air explode into a tight hug all around my torso. The airbag had sensed a crash and triggered an inflation. A few minutes later, another of my little snapshot memories: the feeling of metal sliding gently along my skin, and the sound of scissors slicing through leather, spandex, and nylon.

Having an airbag deploy is a bad sign, and having it cut off of your body in an ambulance is even worse. But, because I was lucky enough to call the whole experience my job, I asked Alpinestars if they could kindly process the crash data housed in the TechAir’s brain and share it with me as they have done for world-championship riders in the past. This isn’t something that everyone can do (yet), and for that I feel fortunate to get a glimpse at what the airbag recorded.

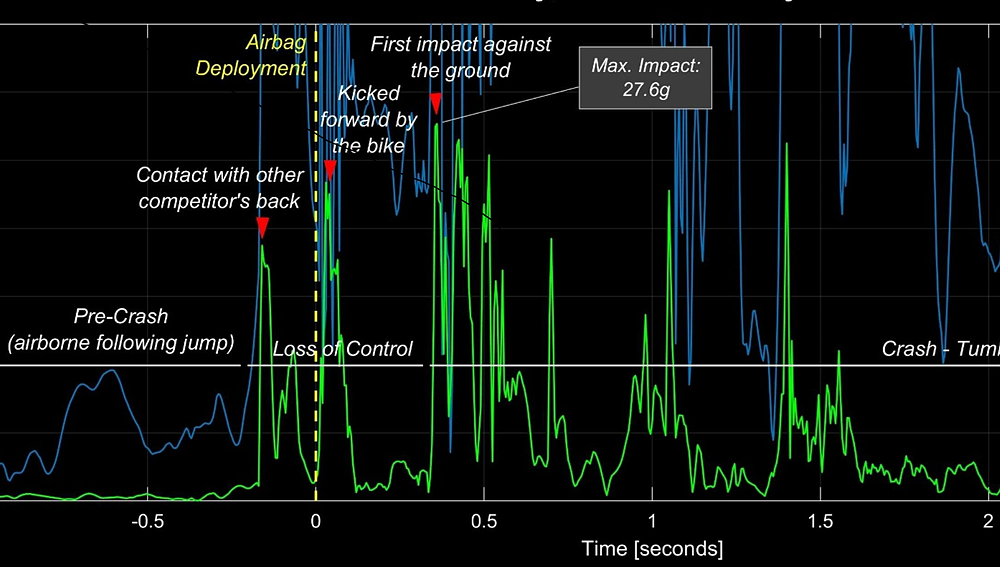

In the graph produced by Alpinestars above, we can see some of what I learned by analyzing the video. About a half second before the incident the central gyroscope is sensing the forces associated with going through a turn, then there’s a release of that force (the slide) that lasts about one third of a second, and then a large spike in force (around 7g) that sent me up in the air.

The next few seconds of data from the TechAir system are the most interesting. According to the analysis from Alpinestars, the airbag deployed less than 0.1 seconds after I was “launched” from the bike. I was airborne for about 0.6 seconds before my largest impact with the ground, the maximum acceleration being measured at 25.78 g. Then, I tumbled down the track for a few seconds until I came to a rest in the gravel.

Sadly, there are still a lot of unanswered questions. Which part of my body hit the ground first? Was there some interaction between my body and the motorcycle? Where in all of this did I break my ankle so badly? When did the bone in my neck break? Within the data, and from looking at the gear I was wearing, there are a few more breadcrumbs to follow.

Foremost, I can’t help but notice the little blip in the central accelerometer data from the TechAir data that seems to show a smaller, “pre-impact” before my maximum g-force was recorded. Based on the fact that the Shoei RF-1400 I was wearing is scarred horribly from the incident, especially on the back, I think this is where the back of my helmet hit the pavement and forced my chin toward my chest. Sharply enough that it fractured the right side transverse process of my C7 vertebrae, evidently.

At that point, it seems my back and torso hit the racetrack and registered the maximum impact. I believe that much because the back of my leathers are severely scuffed and my gloves barely have a scratch. But, because I came down on the back of my head, my legs were still above my body and my feet consequently slapped down onto the pavement, heels first, as the end of the initial blow to the ground. I think that’s when the talus bone in my right ankle broke in half and displaced into a wide, visible-in-X-ray, crack.

What the data means

As interested as I’ve been in piecing together what I know and what I can infer, a lot of the data feels arbitrary. Most of us would pass out when subjected to only a few g of acceleration, if it’s sustained. Impacts are different. So, what the heck does 25-point-something g or 3.45 seconds of “tumbling” mean, practically? Is that a lot? Do I get to feel tough for having survived it?

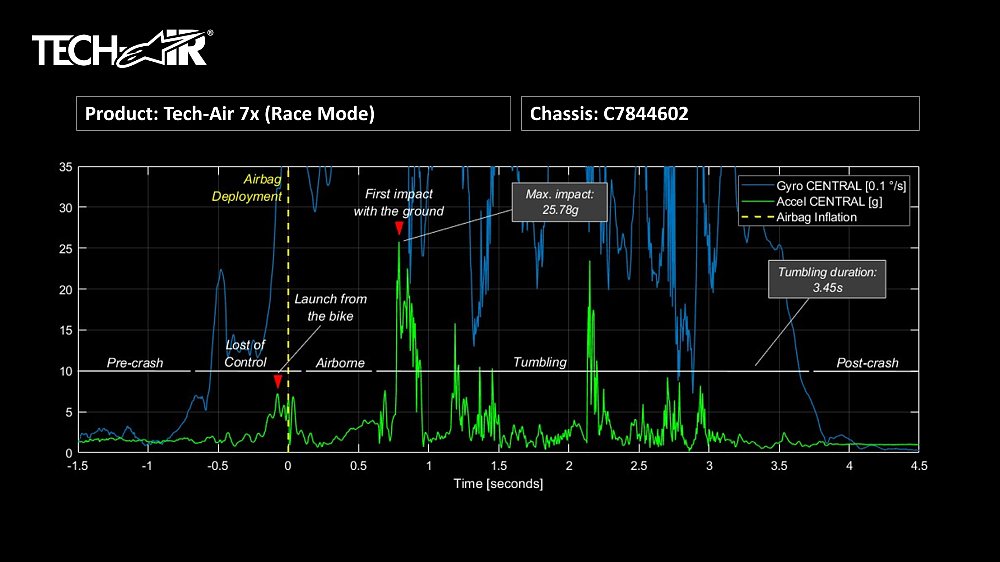

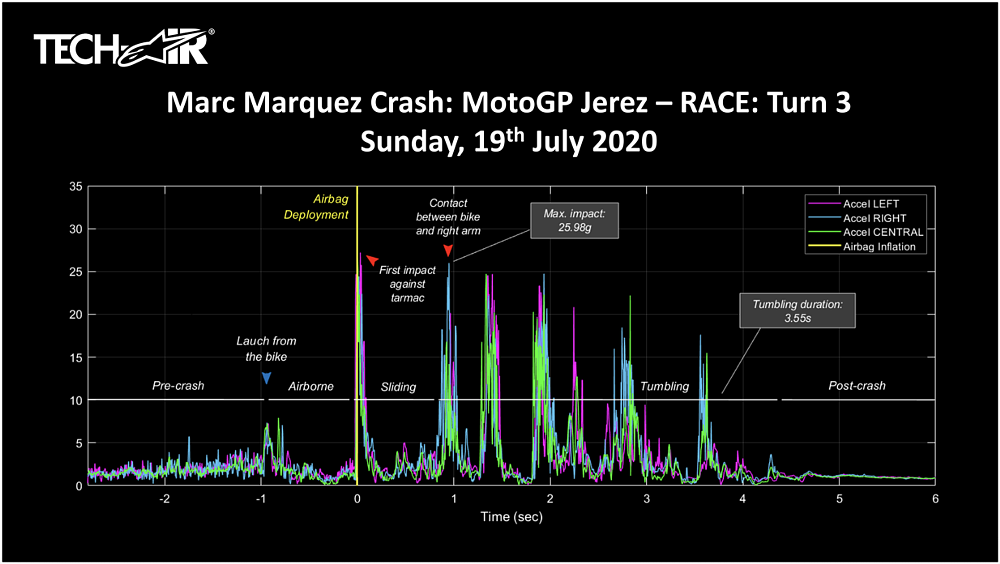

I mentioned before that Alpinestars often digests data from world-championship riders when they crash and then releases it as a way of showing the sophistication of its airbag systems. As it turns out, I found TechAir data from a crash “performed” by one Marc Márquez that nearly matched mine. A little less than a second of air time, maximum impact of 25.98 g, and 3.55 seconds of tumbling.

Marc Márquez has crashed more than a few times, all due respect, but this one is one of his most famous. The highside in Turn 3 of the Jerez Circuit on Sunday, July 19 of 2020, and the resulting broken humerus, nearly ended the elder Márquez’s career. More importantly for me, there’s multi-camera footage of the crash so I have an idea of what that kind of impact and aftermath looks like. And it ain’t pretty.

Márquez’s Honda doesn’t perform the same acrobatics as my KTM did — better tuned suspension, perhaps, or he took more of the upward force from the bike, hence the longer airtime for his body. He landed firmly on his left side, where I believe I was upside down during my crash. Like Márquez, I also ended up ahead of the motorcycle on track (as we can see in the onboard footage when the bike sliding) but, crucially, I wasn’t hit by it as I slid like he was, which might have saved me from further injuries.

That doesn’t answer nearly all of the questions, of course. Marc Márquez’s crash was markedly different than mine, from the tires, to the attitude of the bike, to the rider’s weight, and so on. Every crash is unique and there’s no way to know how things would have been if one of a zillion variables had been different. I was wearing a premium set of boots and I still broke one ankle and sprained the other. Would it have been worse in less advanced gear? We don’t know. It seems if I weren’t wearing gloves at all my hands would have been fine, in this crash. And yet gloves would be the first piece of gear (aside from a helmet) that I’d choose to wear on my body in most situations.

At the very least it makes me feel better about being hurt after the whole thing. If a once-in-a-generation rider made of pure muscle and talent broke his arm in his crash, then I don’t feel as bad being a slightly flabby dad who rides a desk for a living sustaining a nasty ankle break in my wreck. It would have been cooler if I was chasing a world championship but, hey, a paycheck is a paycheck.

The feelings data cannot see

Setting aside the fact that I hit my head hard enough to forget most of what happened, I still struggle with why this crash happened. Anyone who watches MotoGP or World Superbike knows that elite-level roadracers sometimes have this same quandary. “The team looked at the bike’s onboard data” they say in a charming accent, “and I wasn’t doing anything different from the lap before.” Then they shrug and go back to doing situps.

I was out of my track-riding rhythm when I crashed, certainly, honking at my friend and hoping he would do wheelies with me on the next straightaway. Still, I’d taken my proverbial foot off the gas. The machine was on hot, track-day tires with clean, warm pavement underneath them and I had a half-dozen sessions already under my belt that day. Was I a little distracted? Did I let down my guard? Perhaps. But beeping at my buddy is hardly the most difficult thing I’ve done on a motorcycle. I can walk and chew gum, right?

In the past, I have been the good rider who knows why a crash happened, and I’ve even been the really good rider who knows why a crash happens before it has ended. I have also been the bad rider who knows why a crash is going to happen before it starts, and isn’t skilled enough to avoid it. Now, I am the rider who has watched the on-board video dozens of times, analyzed every bit of memory and data available, and still can’t find a crime that fits the punishment.

That’s just the way it goes sometimes. So, I’m trying a different viewpoint. As my fingers slide across the keys, my body largely intact, with my nose gently pulling in the scent of food roasting in the oven, I will crutch into the dining room a new kind of rider. I am the rider who is simply grateful that there is another ride in my future.