When we ride a motorcycle through a corner, there’s a lot of science at work. Grip, force, angles, pressure, and so on. There’s also a lot of seeing and touching, but those sensory inputs don't get translated directly into physics. First, we feel feelings.

We channel patience and poise, sometimes panic, and from that we create body language and movement, we summon determination or some other reaction to change the attitude of the machine. Stuff beyond numbers and equations. So, where does science end and art begin, or vice versa, when we ride? I recently spent two days attending California Superbike School at Laguna Seca Raceway, in search of the answer to this question.

Basics

First things first: I’m using track-based education as the example here, but that doesn’t mean this is about racing or going fast. It’s more common than ever for track schools to invite and cater to riders of bikes not specifically designed for sport riding. The discussions about how to control a bike at speed are universal, as we’ve learned before. My trusty colleague Spurgeon has documented his learnings at California Superbike School not once but twice, and in broad terms I found myself engaged and excited about many of the same concepts he discovered.

Dylan Code, head of CSS and son of legendary speed guru Keith, subscribes to the VARK model of education — that is, Visual, Aural, Reading/writing, and Kinesthetic. For my class, sometimes the same concept was written on a whiteboard, then explained, then drawn, and then shown practically with the use of a prop. There are loads of concepts and forces, both physical and emotional, at work in the midst of every ride on a motorcycle. Presenting them individually with words, images, and demonstrations is a big step toward actually understanding what we are doing on, and to, the machine.

During my two-day, Level 1 and Level 2 courses, we talked about throttle control, turn-in points, the importance of relaxing while riding, reference points, apexes, and trail braking, among other things. If you already know what those things mean, talking about it at length can be illuminating and interesting.

For example: Vision. We all understand sight, in so much as we have it and we can see things. The CSS discussion of vision includes talking about how the human eye takes in images and what the weaknesses are in how information is transferred from eyes to the brain. Like Spurg said in his piece, it’s not just saying “Look where you want to go,” it’s a breakdown of why looking at certain spaces on a road or track makes you perceive different things. I thought it was great.

Art

That’s a good segue, actually, because knowing how an eye works doesn’t explicitly help you control a motorcycle, just like looking farther through a turn doesn’t mean you’re safer, or faster. We have to have confidence to do that, and confidence is a feeling, not an equation. And in the same way that teachers and schools have always tried to explain things, California Superbike School staff work with students to build confidence.

Instructors watch you ride in a parking lot, and then talk to you about body position. They put you on a bike with outriggers that won’t tip over and ask you to lean off, and then coach you through different ways to hold on to the motorcycle. My class did a drill where we walked along a line of markers on the floor, as Dylan watched, to see if our eyes could track smoothly along the path. It was fun. But, still, it’s an interpretation of what we were doing.

Even the classic lead-follow routine relies on riding coaches to form an opinion about our technique and then communicate that to us, at which point we translate it, and then hope to remember what we think they said next time we ride. That’s hard to do, especially when there are so many things going on all at once.

Science

This is where data comes in. There’s no use claiming to be at the apex if the video shows you weren’t, or to say you were wide open if the throttle-position sensor shows that you backed off. Numbers don’t provide judgement of what they witnessed, they just are. In other words: There’s no need to convince you of this critique, buddy, you missed the apex. So, what can you do to fix that next time?

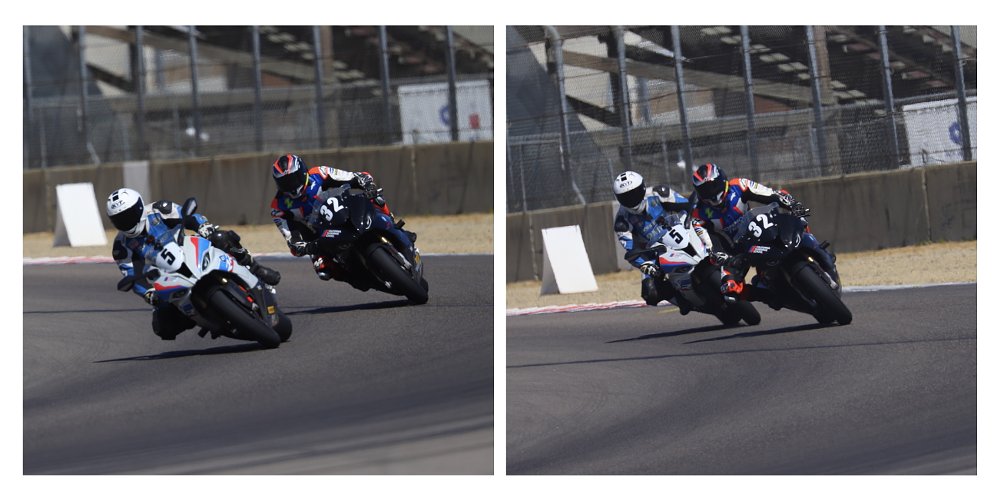

California Superbike School uses specially equipped BMW S 1000 RRs — with an aluminum trellis holding a camera high above the passenger seat, plus data-logging software — to capture on-board footage of each student, and then debrief the video one-on-one. Gone are the theoretical conversations about lines through corners, throttle position, and brake pressure. It’s all right there to be seen, and played back again and again.

I spent a lot of time working on trail braking technique during the second day on track, and the brake-pressure data presented in the onboard video helped challenge me to push my maximum braking to a new level. It’s easy to run wide in a corner or blow a braking zone and think there was no way you were going to make it — when we reach the end of our abilities, we often tell ourselves that it was the end of the bike’s abilities. But, that’s rarely true.

Flying over the fifth-gear crest that is Laguna Seca’s Turn 1, I waited as long as I dared to get on the brakes, and then added another beat before I actually grabbed the lever. I gave up on getting good drive out of Turn 2 or even hitting the second apex and simply tried to make the too-late braking work. I cleared my mind of other lap-time responsibilities and tried to stay calm in those tense moments, focusing only on asking the bike to turn and slow at the same time. Lo and behold, the bike could do it.

Another key in coaching (especially via video review) is tracking where a rider is looking, but it’s tricky to map. Oftentimes you can see a rider’s head turn abruptly as they navigate a corner, indicating that they have switched their point of focus up the track. It’s not always super clear, though, and it’s an especially dark art with average-Joe riders.

Dylan is aiming to take away that guesswork with a nifty set of glasses that are designed to track the focal point of each eye and overlay that information on a video feed pointed forward. Take a look around the room you’re in right now, and imagine that every single thing your eyes settle on has a red crosshair on it — that’s what the video looks like from these glasses, which can be worn inside a motorcycle helmet.

Reviewing the footage from my glasses-on session was fascinating. Tracking eye movement can show immediately how chaotic it feels to ride a motorcycle at speed. The tiny sensors that monitor the movement provide a simultaneous video of the eyeballs, too, which means the video shows what you saw broadly, what exactly you were looking at, and also how much your eyes moved or blinked while you were doing it.

To pick just one of the tidbits I gained from looking at this footage: I came to the realization that visual reference points, while they can all be equally important, do not always deserve the same amount of attention. Dipping through Laguna Seca’s fast (and slightly blind) Turn 6, I noticed that I would lock in on the outside apex for too long — being in third gear, with speed quickly jumping into triple digits, I was tricking myself into thinking the corner went on longer than it did.

I watched footage of my own eye movement and thought “Look up the track, look where you’re going!” And I took that lesson into future sessions, where I would take note of the outside apex and then consciously move my eyes up the track to help convince my brain it was safe to open the throttle and accelerate up the Rahal Straight toward the Corkscrew.

Brush strokes versus key strokes

The way we control a motorcycle is always going to be a blend of technical information — things like how we speed up, slow down, and make the machine turn — combined with the primal feelings and emotions that help guide us while we ride. Breaking down which aspect is more important is like asking which part of breathing is better, inhaling or exhaling; it doesn’t really matter because one without the other simply doesn’t work.

My big takeaway from the art-versus-science conversation is how the value of data can serve any type of rider. We know that world-championship racers analyze ride data to shave tenths of a second off their lap times, but it can help the rest of us, too. There are always too many things to think about in the middle of a corner for any of us to keep track of all of them at once. Reviewing what we did allows us to relive those moments.

We’ve discussed before on Common Tread how our brains struggle to keep up with all of the information they take in as speeds increase, and the big takeaway there was that more time at speed makes a person better at it in the future. That’s just a small facet of how we all try to get better at riding motorbikes.

Seat time is almost always the answer, because every time we ride, we learn. Having video footage of what you did allows you to go back to those situations, whether it was one corner or a full lap, and analyze what you did. Being able to review where you were looking adds a whole new layer to the decisions you made or the feelings you felt.