Dad was an aircraft mechanic. He was born 10 years after the Wright brothers flew, and dreamed of being a pilot himself someday. He passed all the tests but failed the eye exam.

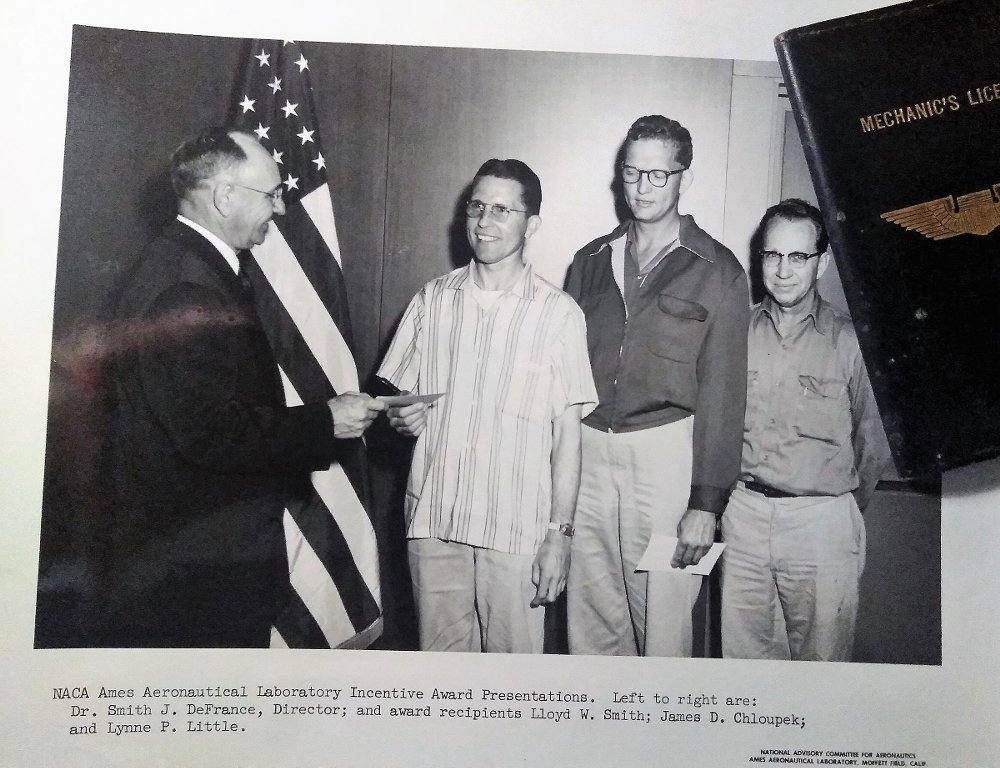

So he did the next best thing and got a job working on planes for companies like Vultee, Convair, and Pan Am, and finished out his career at NASA's Ames Research Center at Moffett Field Naval Air Station in Mountain View, California. In his life he saw the Spruce Goose fly, worked on P-51 Mustangs bound for the war in the Pacific, and shook hands with Neil Armstrong, who was just back from the moon.

Editor's note: Stories about fathers are a rich vein in motorcycling. Here's one example as we wish you a happy Father's Day.

Dad had big, rough-knuckled hands with thick blue veins running down the back, and if I close my eyes I can still see them turning a wrench, or sawing a board, or hammering a nail. To this day I use hand tools exactly the same way he did. Exactly.

We weren't the kind of father and son you see on old sitcoms, playing basketball in the driveway or working on cars together. We had fundamental differences of opinion about certain things. He thought Nixon was trying to save Vietnam from the Communists. I thought Nixon was trying to get me killed by the Communists. Dad wanted me to go to college. I wanted to go to the Daytona 200. It wasn't as if we were constantly at odds, but we didn't have a lot of common ground, and many years passed between us in uneasy silence.

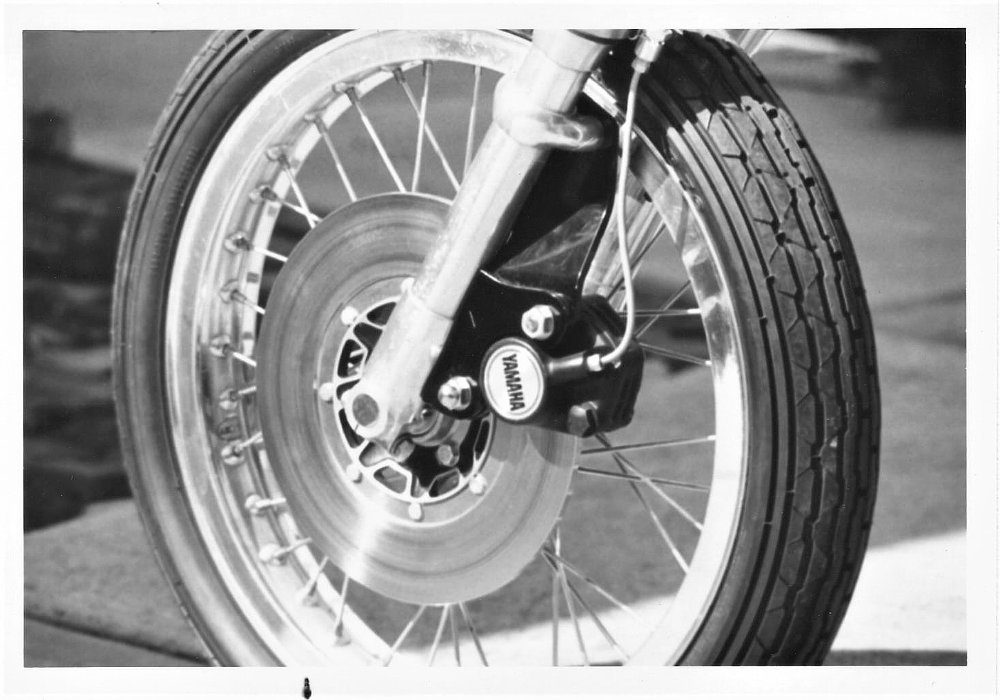

Once during those years, while I was out in the garage trying to graft a Yamaha RD350 front brake caliper to the Ceriani fork on my TD2-B roadracer, he came in and asked what I was doing. As I explained, he squatted beside me, and with his ever-present translucent green mechanical pencil with "Property US Government" stamped on it, he began making sketches on a piece of cardboard, taking several measurements with a small steel ruler he kept in his shirt pocket next to his pencil. Then he stood up, put the pencil and ruler and the sketches in his shirt pocket, and left.

A few hours later he returned with an aluminum bracket he had fabricated at the San Jose airport, where he moonlighted working on avionics systems for private pilots. It was a masterpiece of three-dimensional design, a single piece that spanned the distance between fork and caliper as economically and as elegantly as if da Vinci had dreamed it. Four marks with a center punch and another trip to the airport later, and mounting holes appeared exactly where they needed to be.

At the bike's — and my — professional roadrace debut, Harley-Davidson racing chief and certifiable legend Dick O'Brien stopped in his tracks to admire that bracket. For the next several years, my life was metaphorically in my father's hands every time I grabbed the front brake in a race. I eventually sold the bike, kept the front end for its replacement, and finally sold that bike when I quit racing.

Dad got old, as men will, and needed a quadruple bypass. The years went by, and he needed another, only this time he didn't rebound from it the way he had the first time. When it became obvious there wasn't any point in occupying a hospital bed any longer, he moved into my sister's house to die. I was living a thousand miles away by then, and we bridged the distance that lay between us with frequent phone conversations. Of all the things we could have talked about, that bracket came up more often than not. It was our way of proving we were connected after all.

A month before the end I found a blurry photo of that old race bike, with the bracket barely visible on the off-side of the front wheel, and sent it to him. My sister later told me he had kept it beside his bed, with his Bible and a few other treasures from a life well lived. After he died I brought a lot of his stuff home with me — his letter sweater from his track days in college, mementos of his work with NASA — but I never found that photo. My sister looked, too, and she never found it, either.

They say you can't take it with you. Maybe they're wrong.