Most street motorcycle tires have thin grooves and slits across their surface to evacuate water and maintain better grip in wet conditions. These features are called sipes or siping.

The theoretical “perfect tire” for a dry, smooth road has no grooves at all, like a race slick, because it doesn’t need any features to deal with slippery conditions. Of course, street riders don’t live in that theoretical world with perfect weather and roads, and our tires reflect that reality. Siping is one of the many technologies used by tire designers to keep us upright in the rain. As your motorcycle’s tires roll through, say, a shallow puddle of water on the road surface, siping helps to displace and evacuate the water, promoting tire-road contact and reducing your odds of losing traction. Siping sometimes allows certain tire features to flex when accelerating or braking, further enhancing grip.

Siping might seem obvious to us now, but tires were around for longer than you’d think before those crucial little lines appeared. The earliest rubber tires were solid. John Boyd Dunlop made the first commercially successful air-filled tire in 1888. (Other designs appeared even before the American Civil War!) Treaded automobile tires with large lugs were on the market by 1905, although common tread designs of the time weren’t optimized for wet conditions. Then along came a man named John F. Sipe.

Sipe was employed in a slaughterhouse, so the story goes, and his shoes kept slipping on the blood and other slime that pooled up on the floors. He became so annoyed with his lack of traction that he tried modifying his shoes. Sipe cut thin grooves into his smooth rubber soles, and he was pleased to find that the cuts drastically improved his grip!

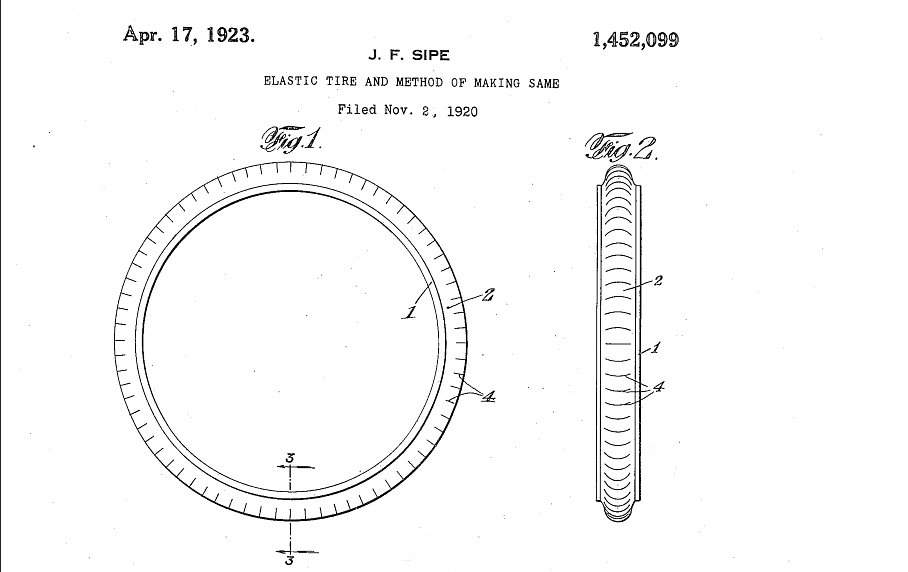

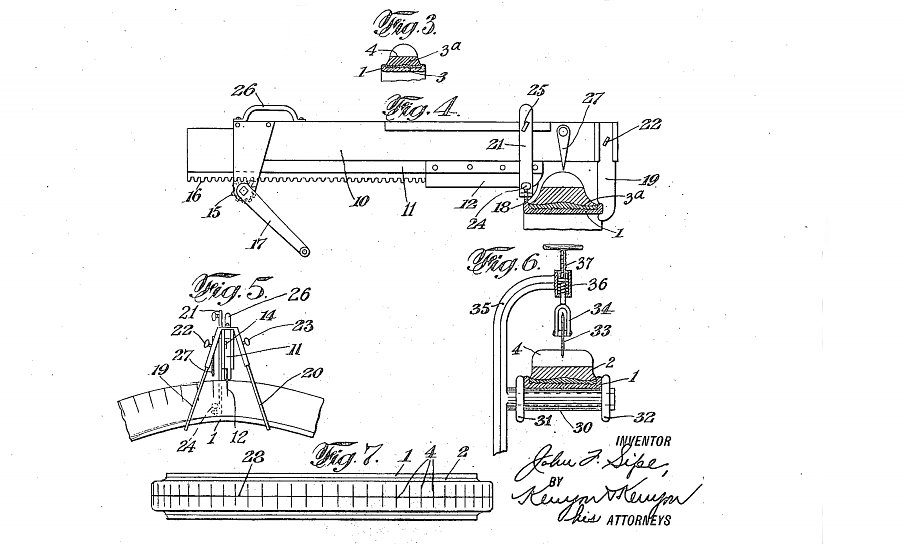

Sipe, a New Yorker but Pennsylvanian by birth, filed his idea with the U.S. Patent Office in 1920, and patent number 1452099 was awarded in 1923. Despite the potentially lucrative market for anti-slip slaughterhouse shoes, Sipe saw much more promise for his discovery in the automotive world, where tires that gripped in wet conditions could make him a fortune.

“The principal object of the invention is to improve at relatively low cost the cushioning, gripping, and tractive qualities of a tire, while at the same time increasing its strength and wearing qualities,” Sipe wrote. “The tire may be incised or cut in an endless variety of ways and some or all of the benefits of my invention be derived.” Just one problem: Sipe's patent only covered solid rubber tires! He didn't secure the process for pneumatic tires, shoes, or other grip applications. Curiously, the word “siping” is absent from his application, though it was in common use by the 1950s.

Even with the solid-tire bungle, siping was named for John F. Sipe, right? Etymology website World Wide Words isn’t so sure. “Against its being an eponym is the absence of any printed record until a quarter century after Mr. Sipe’s patent, even in the technical literature,” writes World Wide Words’ Michael Quinion. The alternative, Quinion suggests, is that “siping” is derived from the Old English “sipe,” which is spoken and used like “seep,” a rough description of water’s movement through a tire with siping. However, he acknowledges the improbability of siping’s connection to Old English, and laments: “As so often, we are left unsatisfied. We may never be able to resolve this intriguing coincidence of names.”

And that’s not the only coincidence in siping’s history. In 1935, one Paul A. Sperry slipped off the deck of his boat and fell into Long Island Sound. Sperry noticed that his cocker spaniel, Prince, didn’t have much of a problem on slippery surfaces. Come to think of it, Prince never slipped on anything...

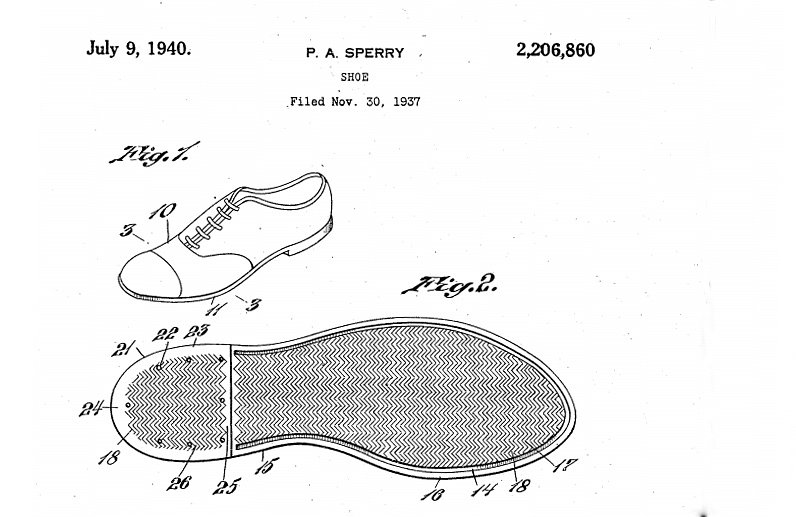

Sperry took a closer look at his dog’s paws and noticed their unique texture, which he tried to replicate on the soles of his shoes. The end result was a herringbone pattern that actually helped on the wet deck. Sperry filed for his patent in 1937, received it in 1940, and made it big after Converse agreed to mold the soles for him. The United States Navy even adopted the shoe for their casual uniform.

Had Sperry ripped off Sipe’s idea? Sperry claimed he thought of it independently, and was ultimately awarded his patent because Sipe’s application focused purely on tires, not shoes. You’ll find that Sperry’s application doesn’t contain the words “sipe” or “siping.” He always describes them as slits, grooves, or recesses. I like the dog story, so I hope it’s true.

Siping to improve wet grip was mainstream by the 1950s and 1960s as tire technology improved at a rapid pace. Synthetic rubber, radial construction, tubeless tires, new compounds, and computer modeling successively pushed the boundaries of grip to the performance levels we enjoy today. My favorite example is the Michelin Road 5’s sipe design.

Tire wear reduces a sipe’s depth, which means the sipe can’t evacuate the same volume of water that it could when it was new. That’s why wet grip usually decreases as a tire ages. Michelin molds trapezoidal reservoirs into the bottom of their sipes to maintain evacuation capacity as the tire wears.

As tire companies develop better compounds, designs, and manufacturing equipment, the humble sipe will surely stay involved. Be sure to appreciate them next time you ride across a bloody slaughterhouse floor, a boat deck, or wet blacktop.