Traffic is light as I buzz along the Juniata River in central Pennsylvania, so I have time to try to imagine the day in the summer of 1997 when my father walked into a motorcycle dealership and, I'm quite certain, made some salesman very happy.

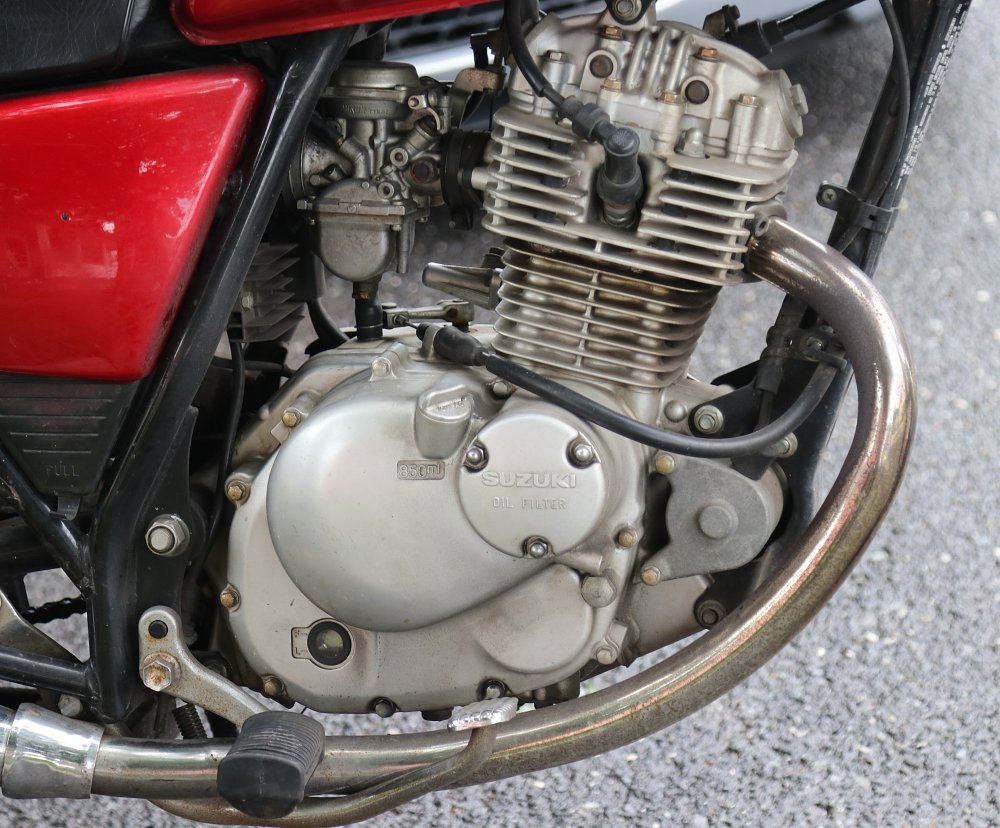

Not a motorcyclist himself, he was not an informed consumer. But he knew what he wanted. He gravitated to a 1996 Suzuki GN125. Unfashionably small and underpowered for the typical U.S. rider, powered by an air-cooled single that hadn't changed since the 1970s, styled with cruiserish touches yet lacking any hope for cred in the bigger-is-better cruiser world, and discontinued in the United States by Suzuki, the little GN had been sitting for a year. I'm sure the dealership owner and sales staff were wondering if it would ever find a buyer. It did.

Over the following years, I gradually came to concede that my father had made the perfect choice, even if he hadn't consulted me. (And I might have steered him wrong if he had asked.) The very qualities that made the GN125 an orphan on a U.S. showroom floor also made it just right for my mother's unusual riding profile, and in any case, it proved its worth simply in the joy it brought for many years.

If that was chapter one, now we are turning the page to chapter three, and that's why I'm taking a 900-mile trip on a three-fourths-scale motorcycle that I'm optimistically estimating might be producing eight or nine horsepower. I'm crossing or clipping the edges of seven states, riding a motorcycle whose value can't be found in a book that's blue or black because, according to that cold, printed accounting, it essentially has none.

It is a rolling family keepsake and it's time to hand it down to the next generation. Unless it throws the rod trying to climb some mountain in Pennsylvania. And yeah, it's probably going to take me a while to get there.

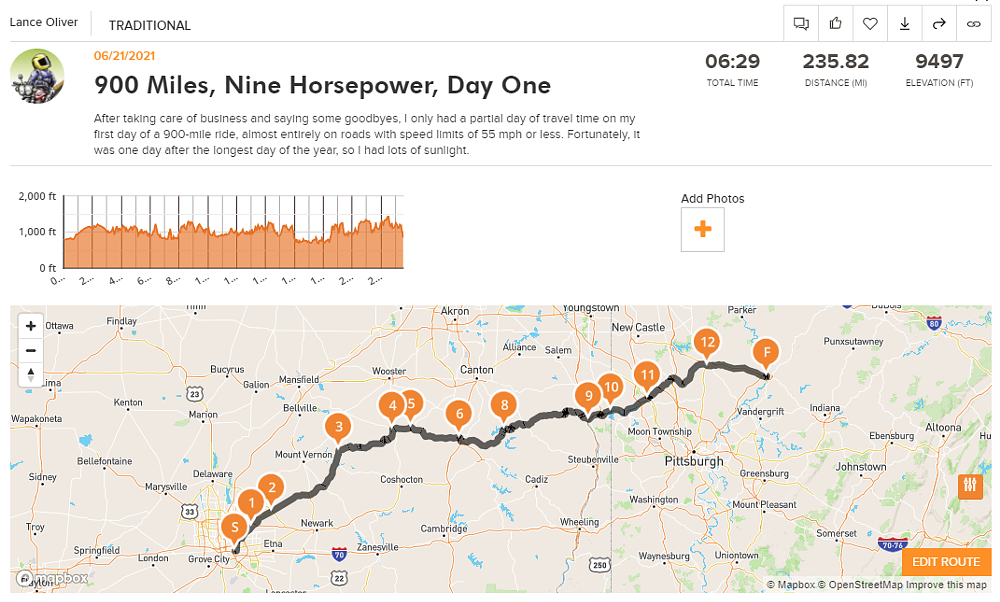

Day one: A favorable tailwind and memories of gentler days

The trip is one I've done at least half a dozen times before, from central Ohio, where I lived until recently, to southern Maine, where my sister lives and my nephews grew up. The difference — and the challenge — this time is the vehicle. The GN125's redline is 10,000 rpm and the "powerband," in my seat-of-the-pants estimation, is about 7,000 rpm to 7,250 rpm, where I enjoy a 0.3 horsepower boost. Approximately. Or maybe I'm imagining that. It won't pull above 7,500 rpm in fifth (top) gear, which is OK with me, because anything beyond 75 percent of redline, when held for long stretches, feels abusive. All of this adds up to a top speed of about 60 mph, under ideal conditions, and even the smallest deviation from "ideal" quickly saps forward progress.

The day I leave Ohio, a front is moving in. The wind chases out the muggy hot days and afternoon thunderstorms we've been having, replacing them with cooler, drier air. Riding into a quartering headwind on a country road through open fields, throttle to the stop, I watch the revs slide down to 6,000 rpm on the tachometer, shift down to fourth, rev back to 8,000, upshift to fifth and watch the inevitable slide begin again. Repeat. Repeat.

Once my course turns more directly eastward, I can feel the cool wind at my back, helping me along. Suddenly, when I'm out in the open among fields, the Suzuki can hold 8,000 rpm in fifth, if I want.

You know the old cliché everyone says about how you notice more on a motorcycle than in a car? How you notice the smells, the changes in temperature? Well, on a small, low-powered motorcycle, you notice things you don't notice on a larger bike. A slight grade that would be an automatic incremental increase in throttle becomes an obstacle to plan for, another reason to check the rearview mirror to see who's coming up behind and whether they look impatient. A headwind I wouldn't notice with 100 horsepower now demands strategic planning. A normally imperceptible tailwind feels like a gentle power boost from nature.

My mother never had to deal with these issues on the GN because she never tried anything so inappropriate as taking it on a long trip. She took purely recreational rides on the quiet lanes in the hills behind their home in West Virginia, through stands of woods and past country homes and a few farms, including the Amish one, where the children would wave at her.

And that's why the GN125 was perfect for her. She never liked scooters. She wanted a motorcycle. But as a returning rider with very limited experience, she needed a light one, easy to handle. She had no need for the highway speeds I was trying to attain as I rode into Pennsylvania, because 45 mph was plenty on the small lanes she rode. And for a couple of years, that was enough.

Then, for another birthday present, I registered her for the first AMA Women and Motorcycling Conference. Though it was only 30 miles from her home, she drove there. Being around all those other women who rode, however, jump-started her enthusiasm. She came home more excited about riding and vowing that she would ride to the next conference, scheduled for two years later, even though it was farther from home. And she did, on a Suzuki GS500E that she bought and I outfitted with a windscreen and soft bags. Later, she would buy a small cruiser for the lower seat. Through it all, though, as the other motorcycles came and went, the GN125 remained. It was the original.

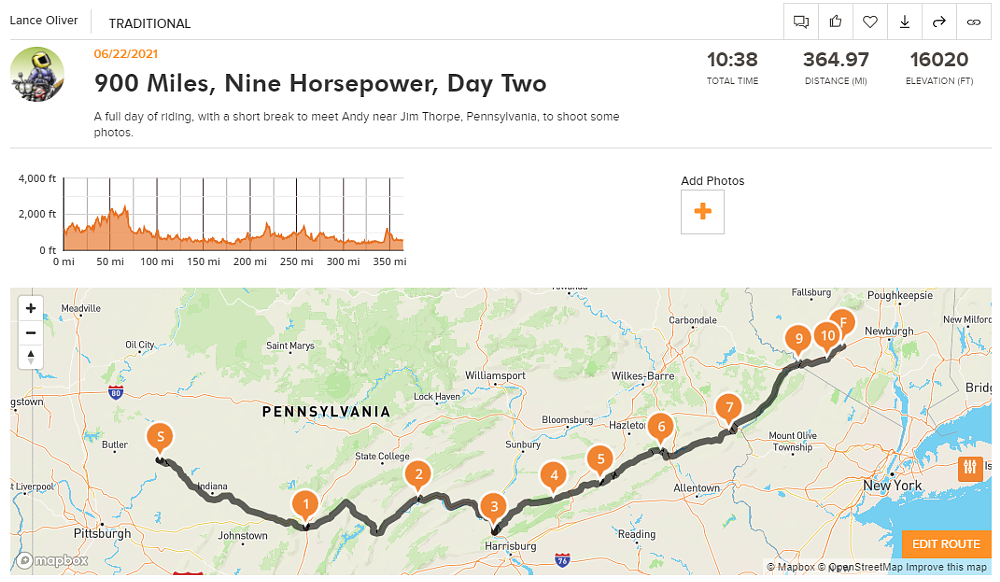

Day two: The joys of simplicity and lightness

Waking up for the second day of the journey brings a couple of surprises. For one thing, I notice that my hands are just slightly swollen from the incessant buzz of the air-cooled single whipped to a fizzy 7,500 rpm frenzy for hours at a time. Another thing, rain has moved through overnight along with the front that chased me as I left Ohio. The morning temperature is now in the high 50s and the air and roads are damp. Yesterday, the forecast called for a cool, sunny day, and the local TV meteorologist is sticking to that story, though all evidence I can see suggests I won't see sunshine all day. (It would turn out I'm right.) The temperature won't be a problem, unless it rains more. Packing super light, I only have one pair of uninsulated, not-waterproof leather gloves. I also only have four shirts. I decide to wear them all. I am a wimp. Many years of living in the tropics ruined me, and I'm often wearing extra layers while the locals are out riding in T-shirts.

I'm amazed, however, at how well the GN125 is running, despite long stretches of full throttle and long hours of buzzing at 75 percent of redline. I shouldn't be surprised. Every year, I would winterize the bike for my mother with stabilizer in the fuel and tuck it away in the shed. About half the time, the tiny jets in the single little carburetor would be gummed up anyway in the spring, requiring a cleaning. It seems true with all machines, but especially ones like this carbureted, air-cooled tiddler: The worst thing you can do to them is let them sit unused. The more they run, the better they run.

The GN125 dates back to the early 1980s and hadn't changed much, except for an upgrade to a front disc brake, by the time my father bought this one in 1997. As a 1996 model, it was one of the last ones imported to the U.S. market, though Suzuki continued to sell them in some other countries. Its simplicity helps keep the weight down, under 250 pounds.

That was a good thing for my mother. The GN was only the second powered two-wheeler she ever rode, after the 1967 Honda 50 (the Super Cub elsewhere) I've written about before. In her 60s and 70s, "easy-to-ride" was an important criterion, one reason she didn't keep the bigger GS500 long.

Several years ago, then well into her 70s, my mother went for one of her short rides on a May afternoon, came home, lost her balance and tipped the GN125 into the bumper of my father's pickup truck. Damage was minimal: a new scratch or two and the speedometer began flinging its pointer around the dial erratically, with no correlation to actual forward progress.

She didn't say anything at the time, but she didn't ride again that summer. Or the next. I didn't bring it up, not wanting to pressure her either way, but on the rare occasions the GN125 was mentioned, she'd simply say to me, "It's yours."

I left it, though, just in case she changed her mind. Just in case she might want to go out to the shed and have a look at it. Just in case maybe the mere fact of having it, even if she wasn't comfortable riding it, might bring her some joy.

For several years, the GN125 sat in the shed, ridden only a few times by me when I visited.

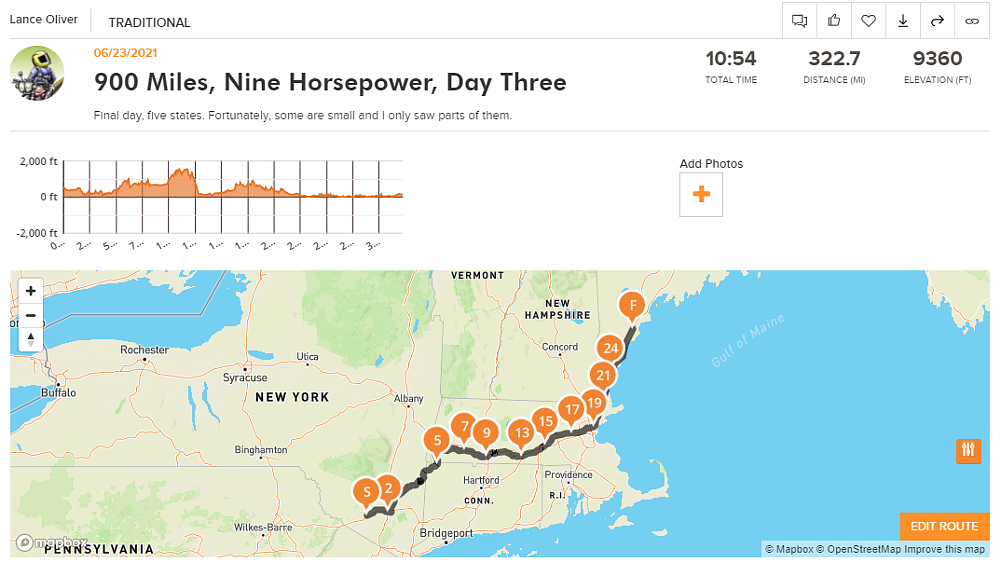

Day three: The 125 cc memory machine

This ride is hopelessly mired in the past. I start day three, now sunny and pleasant, by riding a motorcycle whose design is 40 years old out of a town in New York where I lived 35 years ago.

In Ohio, where my wife and I lived for (an astounding and unexpected, to us) 20 years, I stop for a snack at a small-town coffee shop we visited on one of our anniversary weekend trips and I ride past a country lake where we celebrated another anniversary. In New York, I ride past an apartment I lived in decades ago and see that the rose bush I bought on sale and planted in the postage-stamp back yard is still thriving, unkempt as ever. I cross the Hudson River and roll through the horse farms and undulating hills of Dutchess County, New York, clip the corner of Connecticut and slip into Massachusetts' Berkshires. None of this is the most dramatic motorcycle riding in the country, for sure, and all of it I've ridden before, but it never fails to be pleasant.

The GN125 is a memory machine, too. How could I ever forget the time I borrowed it to ride 600 miles in one day in the Lake Erie Loop fundraiser? Of course most of the memories surrounding the bike are my mother's, but in any case those links to the past are the main reason I'm riding it on this mission of preservation.

It sat in the shed for those years until events moved me to act. In late 2018, the slow-moving, untreatable cancer my father had lived with for years finally caught up with him and took him with the quickness of a sucker punch. It was also clear that my mother, then 80, was not only not going to ride again, but also that her strength and health would make it unwise to try. So this time, when spring came, I pulled the little bike out of storage and set about the task of getting it running so I could put it in my garage, not hers.

For the past two years, I've ridden the GN125 around town for most of my local errands, from pizza or donut runs to trips to the hardware store or wherever I needed to go, putting about 900 miles a year on the little bike. It was so simple just to hop on and go, it became my local transportation just as 125s like this have done for decades for millions of riders around the world.

Then, this year, my wife and I made some big changes, moving to Massachusetts for a new career opportunity for her. More than a new address, it's a new lifestyle, one that's probably overdue. And it involves some downsizing. A fourth motorcycle is just one of several things that didn't fit in. But I had a plan.

I told my mother I thought it was time to pass along the hand-me-down motorcycle to the third generation. She thought that was a great idea. Caelan said he'd be happy to be the steward of the monetarily worthless, sentimentally precious, underpowered little anachronism my father saved from orphanhood 24 years ago.

If he catches even a mild form of the motorcycle bug I have, or even what my mother had, I doubt the GN125 will be his only bike for long. At six feet, six inches tall, he may be, shall we say, ergonomically challenged when riding it, and the GN barely outweighs him. Maybe not the ideal ride for him.

But I think he understands the sentimental value and, in any case, though the price was free, it did come with a catch. If he ever decides to get rid of it, I have right of first refusal. The hand-me-down motorcycle will stay in the family.