Everything in motorcycling is more extreme these days. Superbikes are faster, cruiser engines are bigger, and dirt bikes are more capable than ever. Sometimes it seems like every motorcycle is trying to be the best at one thing, just to be considered for anything. Not the new DR-Z4S.

When Suzuki’s DR-Z400S landed in showrooms 25 years ago, motorcycling was different. Fuel injection and anti-lock brakes were still only trickling in. The machine that won the World Superbike Championship made 120 horsepower in stock trim, and two-stroke machines left a haze of blue smoke in AMA Supercross arenas.

To be a valid dual-sport machine in the year 2000, a bike needed to be able to travel highway speeds and trot down a bumpy trail. A quarter century later, the on- and off-road space is crowded — from the handful of 300 to 500 cc ADV machines available to the hordes of gnarly off-road machines with towering seats and zero body fat — and many of the bases, or roads, are covered. This is the new school of multi-surface riding and, in order for the DR-Z to fit in, a makeover was in order.

The new DR-Z by the numbers

As far as the spec sheet goes, some things have changed and some things have stayed the same. As we covered in the first-look article last November, The DR-Z4 platform gets a healthy batch of updates. A steel, double-cradle frame still holds the DR-Z’s mill, modernized with twin spars to grab the engine from the top instead of the classic single backbone. A removeable, aluminum subframe carries all of the stuff at the stern, perched above a new swingarm.

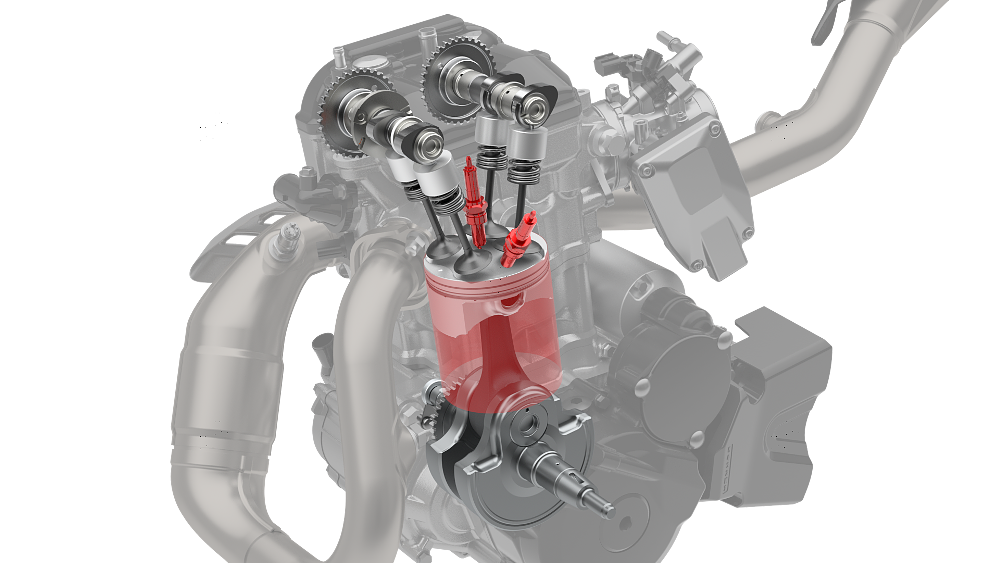

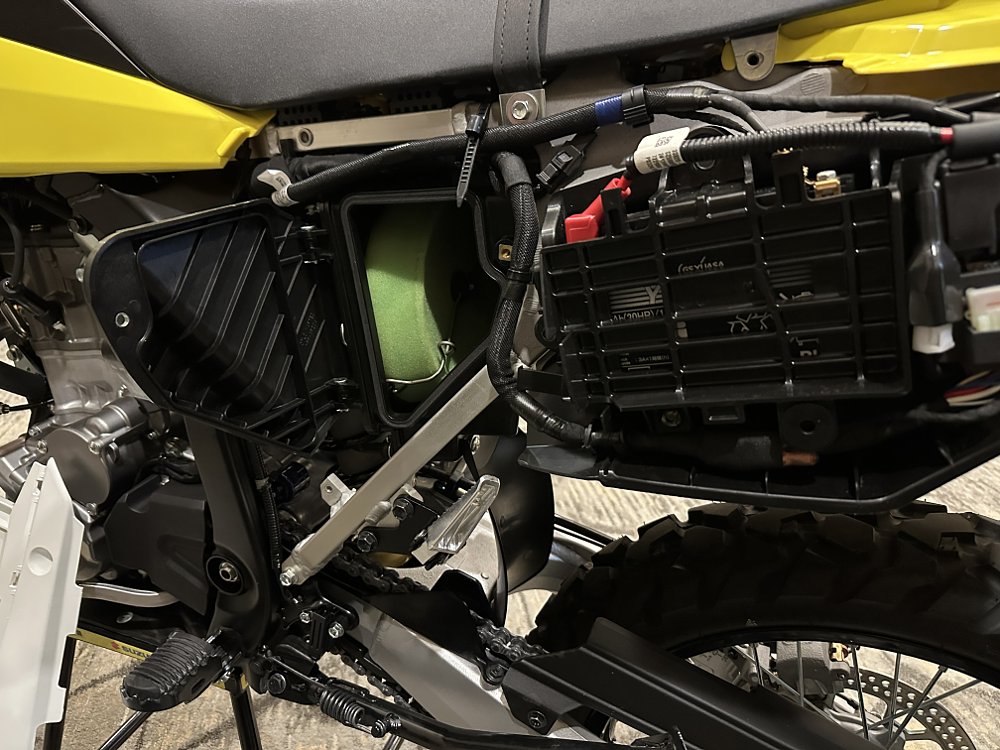

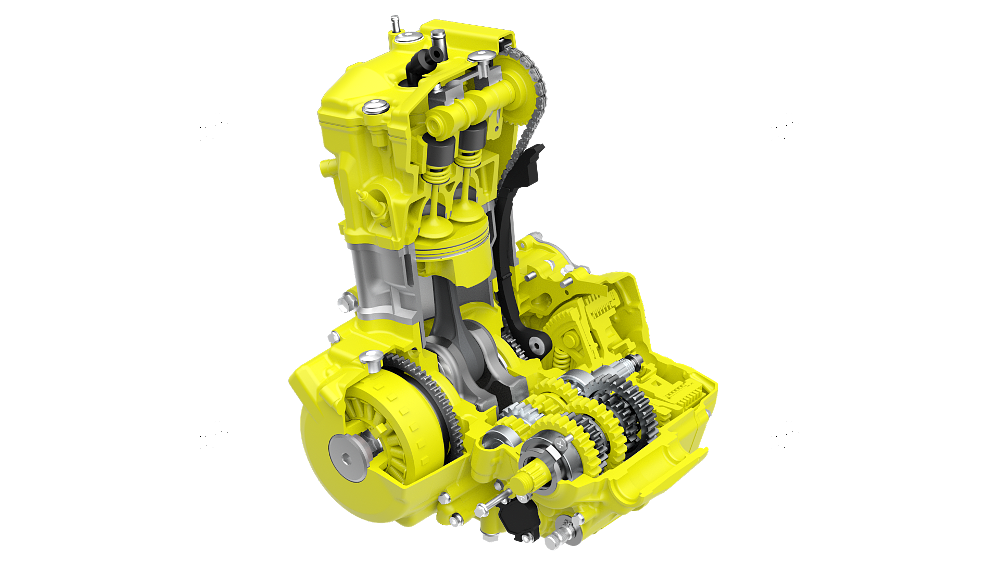

The engine itself has new valves, slightly more aggressive cam profiles, a dual-spark combustion chamber, and a new piston design, all of which is fed by a fuel-injection system (!) via a larger throttle body and ride-by-wire right grip. That technology allowed Suzuki to make available three ride modes, three levels of traction control (plus off), and customizable ABS settings.

To pull the DR-Z out of the dark ages of Euro2 emissions compliance, the new bike predictably has an all-new exhaust system, with two catalytic converters integrated in order to meet Euro5+ standards. Because the outgoing DR-Z400 is a 25-year-old design, Suzuki had to reduce carbon monoxide emissions by 82% and total hydrocarbons by 90%. Big changes and, based on the expressions on the engineers’ faces as they explained it, a little bit of a pain to achieve.

All of this cost Suzuki some weight — the fuel-injection upgrade amounted to more than 16 pounds and introducing ABS added about five pounds. Some of the weight gain was offset elsewhere, but it was a battle that involved a lot of one-step-forward, two-steps-back compromises.

All of the updates to the engine and powertrain highlight the broader dichotomy of updating the DR-Z. Part of the task was to make somewhat generic and obvious updates, like adding EFI and spicier cams, but at the same time it was crucial that everything worked together a lot more efficiently than before. Using titanium intake valves and reducing pumping losses in the crankcase by 20% sounds pretty racy until you realize that it’s all just to stay afloat.

In other words, the DR-Z4S engine’s total power might feel largely identical to the outgoing DR-Z400S, when the truth is it has to work a lot harder to do it. To take a pessimistic and blunt point of view, the new DR-Z holds 0.3 gallons less gas in the tank and weighs a claimed 16 pounds more than the outgoing model, while producing the same amount of power.

Some good news is that the chassis updates thoroughly modernized the DR-Z with little to no downsides. There’s new suspension from KYB (fully adjustable aside from front-spring preload), a stiffer swingarm with a new shock linkage for more linear spring resistance, larger brake rotors front and rear, not to mention LED lighting. Also, some tweaked ergonomics — the handlebar is 1.1 inches higher, the footpegs sit 0.9 inches farther back, and the seat has been made wider and lower by 0.6 inches each.

Of course, to be convincing with a new product it has to look new. From the more vertical, number-plate style headlight shroud to the upswept rear fender and angular plastics, the DR-Z4S looks sharper and more modern. In part because it is, in fact, a lot more modern. The new LED headlight assembly alone is something like 2.5 pounds lighter than the outgoing DR-Z.

From the cockpit

Plopping down in the saddle, the new DR-Z fit my six-foot, two-inch frame just about right. A fairly flat handlebar is rolled back slightly toward the rider and makes for an agreeable, but compact, riding position.

The footpegs feel high but not unreasonable, as does the seat. It’s lower, sure, but 36.2 inches will make for a bit of stretch for anyone under six feet. It’s not supposed to be a touring bike, so as long as your expectations are in check you’ll probably be pretty comfortable.

What’s a little different from most on/off-road bikes these days is the dash and switchgear. The two-color LCD display is humble, but packs a lot of info, and mates with a left control cluster featuring an up/down toggle and a “Mode” button. Street bike stuff.

In the end, I spent about 115 miles on the DR-Z4S, from branches slapping my knuckles on narrow single-track trails to droning down wide, two-lane highways at 60 mph. The most surprising thing about the ride was how competent the DR-Z was in every environment. Maybe it sounds obvious but the more I rode, and the more I thought about the landscape of machines available, the more sense this new Suzuki made.

Take a typical gravel road, a great equalizer for how a motorcycle handles. It’s not a matter of if a bike will feel unstable on loose rocks and washboard, it’s a matter of when and how much confidence you maintain as a rider. The DR-Z4 having mostly dirt-bike DNA helps a lot in these situations. It will wallow and weave as the tires search for stable ground, like any two-wheeled vehicle, but it’s light and narrow enough to be communicative and measured.

If you’re especially nervous in those situations, the tidy new suite of electronics will help. Traction control levels 1 and 2 are designed for the pavement (TC 2 is more conservative) and therefore putting the bike in Level 1 will certainly help keep the rear tire from spinning in the dirt. Maybe too much so. For a little more slip, “G” Mode is available, which allows enough wheelspin to slide around, without getting too sideways.

Maybe more importantly, the anti-lock braking system means the rider can pull the lever and push on the pedal knowing that the wheels won’t lock up entirely. A long hold on a dash-mounted button shuts off ABS on the rear wheel, another long hold will shut off ABS entirely. TC and ride-mode settings can be switched while moving, ABS can only be tweaked when the bike is stopped.

I played around with most combinations of TC and ABS and I think it’s a great package. In my opinion, the bike would be fine with only TC level 1 (call it “street” or something), but one more option doesn’t hurt. Suzuki adopted the same “G” Mode terminology for the DR-Z as the V-Strom 800, but thankfully the programming is different. The engine-testing engineer on hand from Suzuki HQ in Japan told the gathered press that when they tried the same algorithm in the DR-Z it was "negatively evaluated by our test riders.” My thoughts exactly, Sugimoto-san.

Grateful as I am that the DR-Z’s G mode is more lenient, the bike’s charm is partly rooted in the fact that it doesn’t need electronics to be reasonable. Shutting traction control off is what a lot of riders will do, and I’d be surprised if anyone is surprised when they do.

One bike, two sports

Gravel roads are a good testing ground. The true test of a dual-sport, though, is to be able to do both sports. That is, tackle actual off-road riding and cover on-road miles without feeling like a piece of farm equipment. First, the former — how does the DR-Z4S stand up as an outright dirt bike? Part of that depends on what you consider a “real” dirt bike.

The basic profile of a true off-road motorcycle in my head looks something like this — 250 pounds and 12 inches of suspension travel. So, at 333 claimed pounds, the DR-Z4S isn’t even close. Then again, more than 11 inches of suspension travel (likewise with ground clearance) means it has potential.

For me, it was a terrific trail partner. There’s no doubt that it feels heavy compared to a race-ready enduro machine, and the suspension feels mellow and supple. Even so, my 200 pounds never overwhelmed the fork or shock and every last bobble or sketchy moment I experienced was undeniably my own fault, not the bike letting me down.

If I seemed dismissive of the electronics package earlier, tight single-track trails were the place I found myself most impressed with the ride modes. A, B, and C settings offer “aggressive,” “basic,” and “comfort” throttle response, respectively, and it absolutely changes the attitude of the bike. While I spent most of the ride in the linear and predictable B mode, I was glad to have C mode to dull the initial throttle response when riding at low speed. A more experienced rider might like the snappier A mode.

Even dumbed down, it has enough power to lift the front wheel over a tree root or ledge, and a sturdy enough chassis to take the resulting abuse. Maybe a simple way to put it is that, if you mostly ride street bikes the DR-Z4 will feel like a good enough dirt bike to get the job done. If you spend any time on dirt bikes that have maintenance schedules measured in hours, this bike will feel a little cumbersome and unsophisticated. Some of the riders I was with rolled their eyes and chuckled at the DR-Z, pointing out that it just doesn’t feel anywhere near as capable or confidence-inspiring as a true off-roader.

When that trail ends, as they all do, and your dirt bike pokes its little face out onto public roads, that’s when we all wish for more comfort and stability. Jumping into the trickle of cars and trucks on a rural highway is typically a penalty box for dual-sport riders — less so on a DR-Z4S. Gaining speed on pavement the DR-Z is fairly smooth and seems undisturbed by revving up to… well, there’s no tachometer so I can’t say.

Along the paved part of the route, I cantered across open ag land and danced along the cambered twists and turns weaving through Tillamook State Forest. In this context the DR-Z feels spindly and spare, and yet never out of place. The stock, IRC rubber doesn’t buzz or wobble and the suspension feels fine. It’s actually a real treat to swing from side to side on a scenic paved road.

I overheard the same few riders who had made fun of the DR-Z as a dirt bike singing its praises as a street bike. One even said he wants to put this new DR-Z4S seat on other bikes, it’s so dang comfortable. I wouldn’t go that far, but I’ll agree it’s a decent street bike. Every motorcycle is a compromise — for looks, for speed, for comfort, for efficiency, or something else. The DR-Z4S is a pretty darned good one, as far as I can tell. Whether it’s pavement, gravel, or dirt, a highway, a byway, or a trail, the new DR-Z can do it.

The long and the short

However, the pavement portion of the ride did reveal one place that the DR-Z4S simply cannot go, and that is into sixth gear. It was the only glaring problem, to my eye. It arrived each time at around 60 mph when I wished, oh so badly, that I could upshift one more time. And of all the times to add a sixth gear to the DR-Z platform, it does feel like a major update that involves a redesigned engine and frame would be a good time to do it.

I asked Kazuki Hitomi, design engineer for the new powerplant, why there was no sixth gear. How much would it have cost, I wondered, for Suzuki or for the consumer to have another gear. Size and weight of the engine was the main issue, I was told — it would have added two or three kilograms to the total package. “We did not do a calculation for how much it would cost,” he said.

I don’t know if, or how, adding another cog to the gearbox would actually create five or six pounds of weight. But I’m left wondering if the average DR-Z4S owner might trade five pounds for a sixth gear. If you ask me, it’s a rare miss for the new DR-Z, and one that has already caused a lot of conversation. Maybe second only to pricing.

There’s no denying that $9,000 is a lot to ask for a revamped dual-sport from 25 years ago. On the other hand, a quick look at the market shows a pretty big hole where the DR-Z4S is aimed. A buyer can get dual-sport bikes from Honda and Kawasaki for around $5,500, with lower seat heights, less suspension travel, smaller engines, and less advanced rider aids. You could also buy a KTM 390 Enduro R for the same price, and that might be a good option though it is a street bike dressed up as a dirt bike.

Or, there’s Honda’s CRF450RL, which only costs about $1,000 more than a DR-Z4S while having much more power and a serious off-road chassis. Then again, you’ll have to be ready to change the oil every 600 miles, climb up to a 37.2-inch seat, and don’t you dare let those revs drop or it’ll…! Crap, it stalled again. There’s always the Jurassic duo of Honda’s XR650L and Suzuki’s own DR650, for those who simply wish that things would never change.

The DR-Z4S calls for new engine oil every 3,750 miles and a check of valve clearances every 15,000 miles. It’ll also do third-gear wheelies on a gravel road, hop down a narrow trail or across a stream, and accommodate just about any rider’s desired delivery of 38 horsepower. Is all of that worth nine grand? From Suzuki’s standpoint, that hole in the market is either there for a reason, or it’s an opportunity to deliver.

The first 13 miles of my time on the new DR-Z4S jumped from pavement to dirt road, onto single-track, then back to the dirt road and a return to a four-mile jaunt on asphalt again. All in all, 1.6 miles of single-track trail, 6.4 miles of gravel road, and five miles of two-lane blacktop — dual-sporting in a microcosm. There are dozens of motorcycles that could take on that split of riding, and many might be better in certain areas. Suzuki is hoping that by the DR-Z4S being in the middle of the figurative road, it will be the best choice for more actual roads.

| 2025 Suzuki DR-Z4S | |

|---|---|

| Price (MSRP) | $8,999 |

| Engine | 398 cc, liquid-cooled, four-valve, single |

|

Transmission, final drive |

Five-speed, chain |

| Claimed horsepower | 38 @ 8,000 rpm |

| Claimed torque | 27.3 foot-pounds @ 6,500 rpm |

| Frame | Steel twin-spar |

| Front suspension | KYB 46 mm fork, adjustable for compression and rebound damping; 11.0 inches of travel |

| Rear suspension | KYB shock, adjustable for spring preload, compression and rebound damping; 11.6 inches of travel |

| Front brake | Nissin two-piston caliper, 270 mm disc with switchable ABS |

| Rear brake | Nissin single-piston caliper, 240 mm disc with switchable ABS |

| Rake, trail | 27.5 degrees, 4.3 inches |

| Wheelbase | 58.6 inches |

| Seat height | 36.2 inches |

| Fuel capacity | 2.3 gallons |

| Tires | IRC Trail Winner GP-410, 80/100-21 front, 120/80-18 rear |

| Measured weight | 331 pounds |

| Available | Now |

| Warranty | 12 months, unlimited miles |

| More info | suzukicycles.com |