In 2006, Triumph smashed the inline-four orthodoxy of the Supersport class and won bike of the year awards with the Daytona 675. Eleven years later, I finally had the opportunity to ride it.

I was at Hermy's BMW & Triumph in Port Clinton, Pennsylvania, emptying nearly every penny from my sad excuse of a checking account to pay for a 12,000-mile service on my Bonneville. I watched as the mechanic wheeled in a freshly uncrated Daytona 675 wearing Scorched Yellow paint. It was the best looking sport bike I could remember up to that point in my life and the first one to grab my attention.

The Daytona’s beginnings

When John Bloor bought and resurrected Triumph, his first job was to prove to the world that the new company wasn't going to churn out the same outdated designs that had made Triumph infamous in the end. Infamous, in part, for leaving riders stranded beside the road battling Lucas electronics while oil dripped on their boots. When designing the new factory in Hinckley, he looked to Japan for inspiration and managed to secure tours of Kawasaki, Yamaha and Suzuki factories.

The company launched the new generation of Triumphs in 1991 by building a line of motorcycles built around shared three- and four-cylinder engines. The Daytona name went on the fully faired sport model. That first Daytona, powered by a 749 cc triple, was dogged by the press. One review called it "old, heavy, and slow, one best left in the past." It would eventually evolve into the 955 cc Daytona, but it was never a cutting-edge race replica.

In 2000, Triumph decided to enter what was probably the most competitive segment at the time and build a 600 cc inline-four Supersport-class bike, in the form of the TT600. It was followed by the sportier Daytona 600, using the Daytona name for the first time in a new class. Briefly, it was bored out to become the Daytona 650. But none of these efforts made a big dent in the Japanese domination of the class. Instead of trying to beat the Japanese manufacturers at their own game, Triumph took a new approach with the Daytona 675, and that changed everything.

A new generation of Daytona

If those of you reading this were riding in 2006, you’ll know that you couldn’t pick up a motorcycle magazine at the time without finding journalists gushing over Triumph’s new creation. Nearly four years in the making, it took Triumph to a whole new level in the motorcycle community.

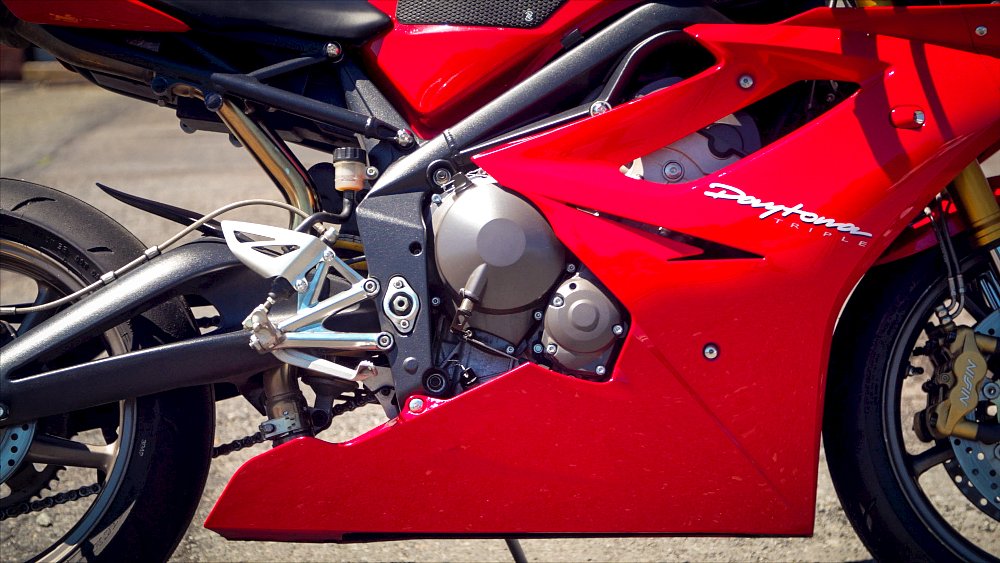

While the bike was all-new from tip to tail, it was the engine that stole the show. The 675 cc, inline triple had a clear displacement advantage over the rest of the middleweight Japanese sportbikes, especially after Kawasaki ceased production of the 636 cc version of their ZX-6R after the 2006 model year.

The additional displacement, combined with the characteristics of a triple engine, meant not only more overall power, but also much more low- to mid-range torque than typically found in an inline four. Looking through old dyno charts published over a decade ago, it was clear that below 11,000 rpm the only bike that could match the Daytona’s power was Ducati’s 749 (the Ducati was the only bike I found as pleasing to look at as the Daytona, but its MSRP of $13,995 made it even less attainable than the 675’s $8,999 price tag). Over 12,000 rpm, the Triumph was only bested by a small handful of the higher revving counterparts, whose power only reached full potential in the final 10 percent of their powerbands.

It wasn’t merely the engine that made this bike so successful. Journalists at the time piled on accolades. They claimed that the new Triumph had better cornering clearance and handling while also being more comfortable. The style was wildly different, modern to the point of being timeless. It’s no surprise that nearly every motorcycle outlet of the day named it Bike of the Year.

The Daytona revisited

A few years after I stood drooling all over Hermy’s showroom floor, I tried to buy a Daytona of my own. I was back in a Triumph dealership, this time on the other side of the country. I was no longer a broke college student, but rather a gainfully employed teacher at Dorsey High School in center-city Los Angeles. (To be clear, being a “gainfully employed teacher” meant I was still broke, just no longer a college student.)

My Bonneville was back in the shop at SoCal Motorcycles in Brea, California, getting outfitted with a new clutch. When I dropped it off, I noticed they had a used 2006 Daytona 675 in Scorched Yellow, identical to the one I had been introduced to two years prior. The bike was prominently displayed in the center of the showroom and with less than 3,000 miles on her, she may as well been a new machine.

It was 2008 and the bottom was still a few months shy from falling out of the economy, so the $6,500 asking price was fair for the time. You might be wondering how I managed to remember the price of a used bike I was considering nearly 10 years ago. Well, I remember it because it was about a grand shy of the price my insurance company wanted to charge a 25-year-old male to own it while residing in Los Angeles County.

Deciding that it didn’t make financial sense to pay more per year in insurance than the value of the bike, the Bonnie happily obliged to carrying me home.

Years passed, my profession changed, and bikes have come and gone. While I’ve been fortunate enough to have had my ass in the seats of more motorcycles than I’ve ever dreamed of (including newer versions of the Daytona 675), I’ve never had the opportunity to ride the original Daytona 675. That is until a few weeks ago.

Thanks to the kindness of our favorite (and only) editor, Lance Oliver, I got a chance to ride his mint 2006 Daytona 675 (although his is Tornado Red) as part of our upcoming Triumph Street Triple RS review.

Carving through the same winding backcountry roads where I learned to ride the Bonneville, I was immediately thankful I didn’t buy this bike while I was learning how to ride. The Daytona was a purpose-built machine, a scalpel if you will, especially when compared to the butter-knife-like handling of my old Bonnie, which was far less likely to cut you should you slip up.

Riding this bike next to the new Street Triple RS proved unfavorable to the basics of the old Daytona. The brakes came across as almost “wooden” (Lance tells me he has a set of Carbon Lorraine pads sitting on the workbench and is interested to see how new pads and fluid refresh the brakes), the turning radius was miserable, the midrange lacked pop and pizzazz, and the ergonomics were painfully uncomfortable when compared to the RS. Yet, it is still seductive. Especially when you’re not considering it against a machine 12 years younger.

As I mentioned earlier, there is something timeless about the styling of this bike. Much like a Honda RC30 or a Ducati 916, this bike has aged perfectly. Even by today’s standards, it still provides plenty of power, winding up quickly. The chassis is narrow and handling is light to the touch. I felt like I was riding through the pages of those reviews I read so many years ago. It’s clear to me why Lance still employs this bike as his regular go-to track weapon.

The future of the Daytona

The motorcycle landscape is very different in 2017 than it was in 2006. This is something Lemmy, Lance, and I discussed as we tested the new Street Triple RS. In 2006, Triumph debuted the new 675 cc engine in the Daytona and later brought out the Street Triple. I think it’s very telling that 11 years later, Triumph has decided to reverse that order and introduce their new 765 cc engine in the Street Triple.

I have seen data from a few manufacturers that show steady growth of their naked-sport segment while sport bike sales sit stagnant. When I asked Triumph PR Specialist Garrett Carter about the future of the Daytona, he told me that Triumph is currently dedicated to selling both models, the Daytona and Street Triple, and that they each fit individual needs. However, he went on to say that they are always constantly looking at how to best optimize their future models, which made me feel a little less confident in the future of the Daytona.

It’s hard for me to imagine that Triumph won't build a 765 cc Daytona, considering the company recently secured the contract to supply engines for Moto2. Beginning in 2019, Triumph’s 765 triple will replace Honda’s 600 cc inline four as the spec engine in one of the most premier forms of motorcycle competition. It's a monumental milestone for the company that originally emulated Japanese manufacturing techniques.

Why make that move if they weren’t planning to have a sport model sitting on their showroom floor to showcase the new engine? At this point, we’ll have to wait and see.

For me, one thing is certain. The 675 cc version of the Daytona was arguably the most influential bike created during the Hinckley era of Triumph’s rich history, even more so that the Speed Triple or the Modern Classics. The Daytona showed the world that Triumph was capable of competing toe-to-toe with the big four on their own turf, and that they would do it their own, unique way.

In 2002, John Bloor spoke to CNN and during the interview he discussed how the Japanese manufacturers that invited him and his team to tour their factories in the mid-1980s simply weren’t afraid of him. I doubt they have the same thoughts today.