Through the years, moto manufacturers have devised various ways of keeping valves properly adjusted.

With each passing year, more and more bikes switch to a shim-under-bucket arrangement. How come? Let’s examine why poppet valves need adjustment, and what brought shims and buckets to their status as king of the heap.

Why do valves need adjusting?

Valves live in the cylinder head, and a valve spring normally holds them closed. They have two tasks: Valves seal the combustion chamber, and either admit air and fuel into the engine (intake valves) or let exhaust gases escape (exhaust valves). If the engine is not a rotary or a two-smoker, the camshaft determines when the valves open (and snap closed) with its eccentric lobes. Depending on the engine, various linkages may be employed between the two, like rocker arms or pushrods.

When a valve is closed, it presses against a ring of hardened alloy called a valve seat. The valve seat is installed in a pocket cut into the cylinder head. Hardened metal is used to cope with the valve slamming into it repeatedly, because the comparatively soft material of most heads, typically iron or aluminum, would quickly erode. In addition to sealing, the valve seat’s second function is to act as a heat sink. By hugging the valve’s contours, the valve seat transfers heat from the valve into the head itself, allowing the valve to cool significantly.

The reason valve adjustments are important is because the constant slamming of the valve causes it to recede ever-deeper into the head. Left unchecked, the tip of the valve stem eventually will contact the piece that actuates it, like the cam or rocker. If that clearance (or "lash," in some parlances) is reduced enough, the valve can actually be held open, creating two problems. First, the valve is unable to dissipate its heat into the head. Second, that small gap allows exhaust gases past the slightly open valve and seat at great speed. This super-hot gas quickly ruins components through a process known as flame cutting, which acts just like it sounds!

So what types of adjusters are there? What’s the best one?

A few common types of adjusters are in use today. Like many things in life, the question of “best” is closely related to what the end user wants from his engine. Here are some of the common ways used to set lash and the pros and cons of each approach.

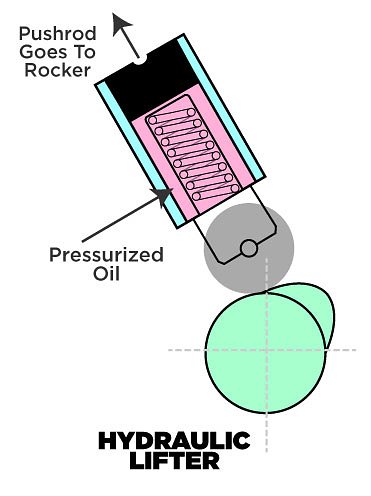

Hydraulic tappets (or “lifters”)

Found primarily on Harley-Davidsons and other low-revving V-twins, these use pressurized engine oil to automatically provide clearance between the rocker arm tip and the valve stem. Valve adjustment occurs automagically every time you ride. (Despite this, my poor wife is still appalled at how often I’m in the garage to “adjust some valves.”)

Desmodromic valves

Found almost exclusively on Ducatis, these valves have no springs. The cam both opens and closes the valves, so both clearances must be adjusted. For that reason, the best way to adjust these valves is to pour a cup of espresso and watch the tech adjust them through the waiting room window.

I’m kidding. They’re not impossible to adjust. But they require a bit more effort than some simpler types.

Ducati’s desmodromic valves were originally designed to sidestep performance barriers imposed by early valve springs. Metallurgy, cam design, and better understanding of cam timing rendered most of those problems moot, but Ducati stuck with the system, which is now part of the company's identity, like V-twins for Harley.

Screw-and-locknut adjusters

This was the dominant style of adjuster found in most early Japanese bikes, because their design usually puts the cam over the head. (Known as “overhead cams”, this engine layout is the main competitor to pushrod designs, favored by marques like Harley, that locate the cam down in the belly of the engine.) All parts necessary for adjusting are self-contained. Thus, they typically do not require additional parts other than the occasional gasket for service access.

Screw-and-locknut adjusters are easily serviced by home mechanics and shop wrenches alike. As the name implies, a threaded adjuster located on the rockers is turned to achieve the correct lash, and a locknut holds the adjuster in position. The adjustment parts are self-contained, so the mechanic doesn't have to supply parts, other than maybe an odd gasket. Screw-and-locknut adjusters were (and still are) used in applications where maximum performance is not the sole focus: Think dual-sports, some big-bore naked bikes, and small-displacement commuter or learner bikes.

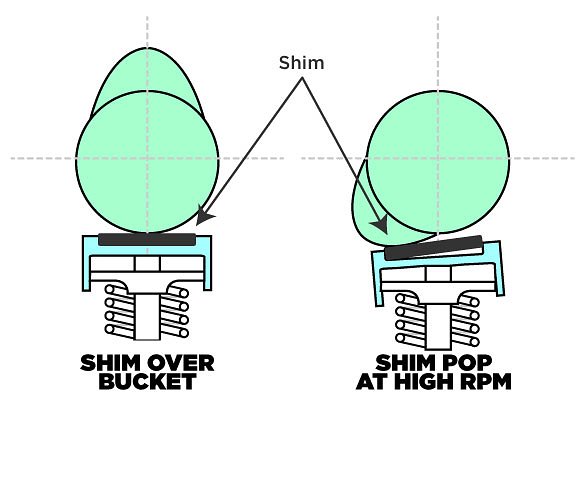

Shim-over-bucket “adjusters”

In this design, an inverted “bucket” sits over the valve stem, and a shim sits atop the bucket to create the necessary lash. One can’t really “adjust” the valve lash on this setup. To change the clearance, the shim is replaced with one of a different thickness. Shims are readily available at most motorcycle shops and dealers.

The shim-over-bucket setup became the preferred method because engineers wanted to eliminate rocker arms. Rather than actuating valves with a rocker arm, the cam itself opens the valve. This lightens the valve train (freeing up horsepower), allows for more precise valve timing, and also leads to longer valve inspection and adjustment intervals, because there are fewer parts to wear. (Ever-improving valve seat metallurgy simultaneously helped.) Extended valve adjustment intervals ease some of the pain caused by newer designs that require more time spent removing bodywork and tightly packaged engines with difficult access.

There's a potential problem with shim-over-bucket adjusters in high-performance engines, however. There are times when an engine can spin so fast that the valve spring cannot snap the valve closed before the cam attempts to open it again. Effectively, for a split second, no load is placed upon the valve by the spring. (The phenomenon is known as valve float.) That lack of spring pressure, coupled with the rotational “wiping” action of the cam lobe, can actually “shoot” a shim out of its captive spot on top of the bucket, eliminating clearance entirely! See the illustration above.

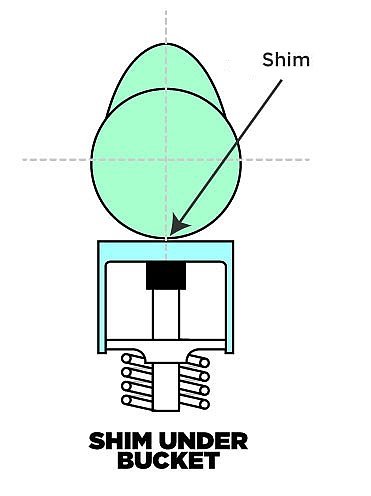

Shim-under-bucket “adjusters”

So when it comes to valves on modern motorcycles, that's why things are the way they are.

Engineers have gone to some pretty great lengths to correctly maintain a few thousandths of an inch of space between vital engine components, which should encourage you to check and adjust your valves! If you remember one thing from this article about valve lash, let it be the following:

Too loose is better than too tight, and valves tighten as you pile on miles. A quiet engine should scare you a bit. Those close to me know I’m fond of saying, “Loud valves save lives!”