Picture an Allied soldier escaping from the Nazis on a motorcycle. I bet you just visualized the famous jump scene from "The Great Escape." Although that movie was inspired by a real POW prison break, the jump sprang only from a screenwriter’s imagination. Nothing like that ever happened.

But there was a group of British soldiers deep inside Nazi territory when Hitler gave the order to invade Poland. This is the story of the Royal Army’s 1939 ISDT team, and their real-life "Great Escape."

Germany annexes Austria and seizes a propaganda opportunity

Adolf Hitler was born in Austria and, although he lived in Germany, he remained an Austrian citizen until 1925. If anything, the Nazi party was even more popular in his homeland than it was in Germany. In March 1938, Hitler’s "Anschluss" made Austria part of the Third Reich. Hitler was given a hero’s welcome in Linz.

A prestigious international sporting event was just the thing to legitimize Austria’s new status as a German province. Since Germany had earned the right to stage the upcoming International Six Days Trial — often called "the Olympics of motorcycling" — they chose to hold it in Salzburg. It was a spectacular alpine setting, already the home of a major music festival (and of the Von Trapp family singers, of "Sound of Music" fame).

While Hitler consolidated his power, Britain responded to his political bullying and ominous military buildup with a mixture of appeasement and halfhearted rearmament. Military strategists on both sides realized that the next war would be far more mechanized than the previous one. Motorcycles would play a small but significant role. The Royal Army realized that the ISDT was an excellent test of military motorcyclists’ combat readiness. So, in 1938, the Army entered a team in the Six Days. It was held in Wales that year.

Three soldiers from the Royal Tank Corps — Cpl. Fred Rist, Cpl. R. Gillam, and Sgt. J.T. Dalby — did well against two German military teams. But overall, the Army team was poorly prepared, and their performance proved that military riders, machine specifications, and preparation had fallen far behind their civilian counterparts.

War looms, Army motorcyclists train

After Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain’s embarrassing “peace for our time” concession to Hitler in September of 1938, the British Parliament spent the first half of 1939 assuring the population that war was unlikely. But, its actions belied those words; the government published evacuation plans in London newspapers and dug trenches in public parks for cover during air raids.

After its rude awakening in Wales, the Army vowed to redeem itself. Dispatch riders were encouraged to enter civilian competitions to sharpen their skills. They were allowed to use their issue machines and were provided with free fuel and oil.

Rist, the Tank Corps sergeant, took advantage of this "sponsorship" to win the Travers Trophy Trial, an achievement made more noteworthy by the fact that he was still virtually a novice. Later, he teamed up with his fellow corpsmen, Paddy Doyle and Jackie Wood, to win the team event at the Cotswold Cup Trials. By beating several high-profile manufacturers’ teams, the trio established themselves as the best Army motorcyclists.

In June, Col. C.V. Bennett assembled a dozen crack riders. They were to spend the summer at Aldershot, a sprawling English military base, in full-time preparation for the Six Days. Their goal was nothing less than to win the Hühnlein Trophy, which was the award presented to the top military team. Over 11 weeks, the soldiers would train and be tested, then three squads of three riders would be selected to go to Salzburg.

Bennett leaned on the manufacturers of the Army’s motorcycles (BSA, Norton, and Matchless) for support. Each firm agreed to prepare works machines for the trial, and provide a factory service representative.

The team’s daily routine at Aldershot began with calisthenics and swimming, led by Sgt. Rist. Then there was riding practice on sand, grass, and gravel. They were tested on everything from changing tires and cables to assembling carburetors and clutches. Daily "trials" of up to 200 miles often lasted until late in the afternoon. In the evening, each rider returned to his quarters with his machine, where he performed his own maintenance. Bikes were presented for inspection at 8:30 the next morning and the cycle began again.

Factory experts gave workshops on setup and service, and a technician from Dunlop taught them the fastest way to change a tire. In July, the Army lads were invited to the Bagshot Heath scrambles track, where they watched a special committee of the Auto-Cycle Union, the FIM affiliate, select elite civilian riders for the British Trophy and Vase teams.

The Army brought in the country’s top scrambles riders as visiting coaches. They booked Brooklands and Donington for high-speed practice. Bennett was taking his job seriously; at the end of the month, the team was inspected by Major-General H.R.S. Massy, no less than the Director of Military Training.

August: A Royal Army motorcycle racing team is chosen

On August 8, Britain’s future leader, Winston Churchill, spoke on American radio. A hush had fallen over Europe, he said. “It is the hush of suspense, and in many lands it is the hush of fear.” British competitors debated the wisdom of traveling into Nazi territory at a time when war seemed so imminent.

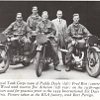

At Aldershot, there was suspense too, as Bennett selected the riders for Salzburg. They were:

| Riding 490 Norton | Riding 347 Matchless | Riding 496 BSA |

| Lt. J.F. Riley | Sgt.-Major B. Mackay | Sgt. F.M. Rist |

| Sgt. J.T. Dalby | Sgt. O. Davies | Cpl. A.C. Doyle |

| Cpl. G. M. Berry | B.Q.M.S. E. Smith | Pvt. J.L. Wood |

Not leaving anything to chance, BSA equipped the A squad with their newest Gold Stars.

British competitors ride to Salzburg

Towards mid-August, the team set out on their competition machines towards Salzburg, in order to get practice on "continental" roads. They were accompanied by a loose convoy of more than 50 civilian competitors (making up the Trophy and Vase teams, as well as club and manufacturers’ teams.)

Most of the British arrived a few days early. Salzburg’s streets were decked with Nazi regalia — decoration for the music festival, and because Hitler himself had established a summer base 15 minutes away at Berchtesgaden. One night at the opera, the crowd spent as much time with its opera glasses trained on the balconies as they did towards the stage; Herr Hitler was in the house.

The event was put on by the Nationalsozialistisches Kraftfahrkorps. The NSKK was an official paramilitary arm of the Nazi Party. There were so many uniforms in evidence at the Six Days check-in — both amongst the competitors and the organizers — that some of the civilian riders wondered, was the ISDT still a civilian event with one military trophy, or had it become a military event, with a few civilian classes? Dozens of riders had been entered by the NSKK, Luftwaffe, and SS.

Day one: Monday, August 21, 1939

General Hühnlein (sponsor of the military trophy) was present at the start of the 1939 ISDT, as riders took off on a 295-kilometer loop into what had, only the previous summer, been the free country of Czechoslovakia.

The first day was relatively easy, but it still took its toll on the Army teams. Berry (Norton) came off after hitting a dog. The crash destroyed his twist-grip, but he continued, pulling the bare cable to control his throttle. Later that day Smith (Matchless) was blinded by the dust of a passing rider, and hit a bus! He continued with bent forks. Finally, Lt. Riley’s Norton split its gas tank. The A team of Rist, Doyle, and Wood, however, lost no marks, and was going strong.

Editor's note: Additional photos of the 1939 ISDT can be seen at the Austrian Technical Museum web site.

Day two: Tuesday, August 22

Tuesday’s loop was shorter, but sharper. A number of competitors retired, including two of the Army’s Norton riders, and one from the Matchless squad. On the Nortons, Berry gave up when his replacement twistgrip would not work. Riley had managed to seal his cracked fuel tank with soap(!) earlier, but the split worsened. Smith, on a Matchless, finally succumbed to the bent forks and wheel he’d suffered in his previous collision.

On the same day, the Reich concluded a treaty with the Soviets. German riders and officials reacted warmly to this news. They believed their own propaganda, which suggested that the treaty reduced the risk of war with Poland. In fact, the opposite was true. One of the treaty’s secret clauses gave eastern Poland to Russia. Hitler no longer needed to fear that his attack on Poland would anger the Russians, who also craved Polish territory.

This was what the dictator had been waiting for. He convened a meeting of his top generals at his summer headquarters — they must have almost been able to hear the roar of trials motorcycles in the clear mountain air. He told them his decision to invade Poland was now “irrevocable.” The generals were instructed to have their forces ready to move by the weekend.

Day three: French riders are ordered to return home

Wednesday’s route took competitors over the Grossglockner pass, a 23-kilometer climb that included numerous hairpin turns. Even at the end of summer, the surrounding peaks were snow-capped. A late thunderstorm put down the dust, and seemed to favor the British riders.

That evening, competitors crowded around radios listening to the BBC news broadcast; they heard that France had ordered its citizens to leave Germany within 24 hours. Several racers suggested the British contingent should do as much, but the team managers were against the idea, especially as there were British teams poised to win all the important trophies.

The British civilians were heartened by the fact that their Army team seemed perfectly calm.

Day four: A showcase for Nazi motorcycle pharmaceutical technology

The various NSKK and SS teams were drawn from the same mechanized units that would soon be unleashed in the blitzkrieg attacks that marked the early phases of WWII. Those soldiers were issued millions of doses of a drug called Pervitin, made by Temmler, a German pharmaceutical company. We now call the same drug by a different name: crystal meth.

In the late 1930s, Pervitin was an over-the-counter drug used by millions of Germans who craved a pick-me-up. Although some German doctors decried the harmful effects of long-term use, military physicians seized on Pervitin as a potential tactical advantage that would allow soldiers to fight for days on end without pausing to rest. The Wehrmacht ordered and distributed millions of doses, and it’s likely that many German competitors were partaking.

On Thursday, British competitors again took to the course, while team managers sent telegram after telegram, desperate for any information or advice. Their uncertainty lasted all that day. Long after the competitors had returned to parc fermé, Norton Motors wired instructions that their team was to withdraw and return right away. Moments later, the British Consul General in Berlin, acting on instructions from the Foreign Office in London, warned all British subjects to leave Germany immediately.

The German organizers begged them not to go. Event officials, all Nazis, promised the team managers that if trouble started, they would accompany them to the border themselves to ensure a safe passage out of the country.

The three teams entered by the British War Office had no say in the matter; they were soldiers on duty, under the command of Col. Bennett. They cheered when he told them they’d stay and compete, although Bennett’s decision was not influenced by his racers’ competitive instincts, or the Nazis’ entreaties to remain. As far as Bennett was concerned, it was simply a matter of protocol. His orders came from the War Office, not the Foreign Office. Marjorie Cottle, the lone female competitor, later told a motorcycle magazine that she saw no reason to cut and run, either. If it was safe enough for the Army, it was safe enough for her.

Day five: Delayed orders!

At dawn, most of the civilians packed and loaded their machines to leave the country. The Army’s lads withdrew their bikes from the enclosure, and headed off according to schedule. One exception was Dalby, the final Norton runner, whose gas tank had also begun to split. Col. Bennett didn’t want to risk one of his men being stranded alone in the countryside, so Dalby was withdrawn from competition.

Things seemed calm enough, and after seeing his riders off, Bennett and Bert Perrigo (who was tagging along as BSA’s technical representative) went for a swim. When they returned to their hotel, they found orders from the War Office instructing the team to leave for Switzerland immediately. Ironically, the orders had been issued Thursday, even before British civilians had been told to leave, but the paperwork had mysteriously been delayed in transit.

While they must have had their doubts about the political situation, the A team led by Fred Rist was still in the running for the top military trophy. In fact, the three riders had not lost a single point between them in five grueling days. As the exhausted squad reached the finish line on Friday, they found Col. Bennett waiting with new orders: Prepare for immediate departure.

The last British convoy out of Salzburg consisted of the racers, "fitters," officers, and factory reps; Cottle and three other civilian competitors; and one other woman, a Miss Bunge, representing the Auto-Cycle Union. They formed a column of two trucks, two cars, and 15 motorcycles. They were accompanied by Bennett’s German liaison officer, the very downcast Col. Grimm.

The British "Internationals" were far from the only soldiers on the move. The German invasion of Poland was set for 4:30 a.m. the next morning. Well over a million German troops began moving towards the border under cover of darkness.

Fuel was tightly rationed, but Herr Jaeger, of Shell’s Munich office, provided the group with enough precious gasoline to get to Switzerland. The British contingent — their day had begun so long ago, at 4 a.m. — rode right through the night. Once, the motorcyclists were halted and questioned by German soldiers at length, until Grimm came to the rescue. It was pouring rain, and cold. Despite this discomfort, they were so utterly knackered that more than one rider dozed off, waking with a start after hitting the curbs.

Day six: An Axis-only affair

On paper, the final day, Saturday, was to be the easiest by far. It began with an easy dash up and down the autobahn, and concluded with one last "special test." Perrigo, BSA’s factory man, suspected that Nazi officials had smoothed the final scrambles course as much as possible in order to suit the German motorcycles, which were fast but heavy. In spite of this, he was sure the Hühnlein Trophy was within British grasp. He noted the similarity between the final test and the team’s practice tracks at Aldershot and Bagshot Heath.

Perrigo’s optimism was probably well founded. Rist became a legendary sandtrack racer after the war; so he, for one, would have done well on the smooth gravel track. It’s hard to say what would have given them more satisfaction, winning the event as racers, or accepting a trophy from a German general as soldiers in the Royal Army. That symbolism would be lost on no one. The racers undoubtedly would have preferred to race the final day, but they were soldiers first, and orders were orders.

WWII got off to a false start

While the British convoy was riding through the night to Switzerland, Hitler had an uncharacteristic crisis of confidence. First, Britain reaffirmed its commitment to come to Poland’s aid. Then, Mussolini screwed up his nerve and informed Hitler that Italy’s military was not yet ready to help if Britain (or France, for that matter) joined the fray.

The Führer called off the invasion. Poland got a brief reprieve, although it took hours for new orders to reach all the men in the field, and some German advance units had already pushed in.

So, on the morning of the sixth day, instead of charging off to capture the Hühnlein Trophy, the Army team crossed into Switzerland. After seeing the last of his men to safety, Col. Bennett bade farewell to Col. Grimm, and stepped across the border himself. It would be a long time before an officer of the British Army would again shake hands, as a friend, with of an officer of the Wehrmacht.

The British contingent rode almost nonstop through Switzerland and across northern France, to the ferry docks at Calais. They were no sooner home than war was on for real. England declared war on Germany on September 3, 1939. The United States entered the war two years, three months, and eight days later.

Left to compete in their event virtually alone, the Germans won all the major ISDT trophies. The results were never ratified by the FIM.