We open on a dark and spare conference room inside an industrial building in Hamamatsu, Japan, 130 miles southwest of Tokyo.

It is 2005. I’m massively jetlagged, as is my book publisher sitting at my elbow. The hired interpreter's English is not fantastic, though it's better than my Japanese by a long shot. Across the table are Suzuki engineers, almost all of them individuals who had a strong influence on what is arguably the most important motorcycle the company has ever built: the GSX-R. A book to celebrate the bike’s two decades of dominance has barely started.

I ask an easy question about the origins of the GSX-R's design. An uncomfortable silence grips the room. Each engineer considers the question, translated into his mother tongue, and casts a wary glance at the managers who are also seated at the table. A throat clears. One engineer speaks up, and an anodyne answer arrives through the interpreter. I ask a follow-on question, trying to dig a little deeper, and a similar response follows. After two hours of this, I begin to despair that I'll ever get any of these men on the record with their true thoughts on the GSX-R — how it was developed, the wrong turns taken over its then-20-year lifespan. Amazingly, even in 2005, more than two decades after the GSX-R was developed, many of those who were part of the motorcycle's early life are still with the company in some capacity, and the desire to commit a career-limiting comment to an American journalist hovered somewhere near absolute zero.

David and I received some warning that Yokouchi might be a different kind of interview. At the appointed hour, he strode into the room and offered the normal pleasantries. I was ready to go, reviewing my notes and first handful of questions, girding myself for another round of pulling teeth, and just turning toward the interpreter to present the first one when Yokouchi asked in perfectly good English, "Shall we begin?" Surprised, David and I had barely nodded when Yokouchi stood, stepped to the white board and began what would be a two-hour lecture on the GSX-R — something I described in the book as more like a sermon. At 60-plus, Yokouchi was potently energetic, as clear minded about the topic as anyone who had spent two decades spreading the faith. Thank goodness I was recording the interview because it took me several beats before I thought to begin writing my own notes. A moment later, David and I exchanged glances that said, "We got it. This is the kernel of the book; it all starts here."

The origins of the sport bike

In the world of supersport bikes — a term that hadn't really gained currency by the early 1980s — the Suzuki GSX-R750 is the turning point, the marker in time motorcyclists would later recognize as altering the course of an entire industry. That's not exactly true. Through the late 1970s and into the early '80s, Japan had begun moving away from its sport bike orthodoxy, developing more powerful four-stroke bikes and developing sport- or even race-oriented submodels. Think the half-faired GS1000S or Kawasaki's GPz models. Then, in 1982 Honda dropped the V45 Interceptor into the mix, high-tech V-four, rectangular-section steel frame, 16-inch front wheel and all. It was pure sci-fi in a world of air-cooled, across-the-frame fours in round-tube chassis rolling on 18-inch wheels. Others would follow, with Kawasaki launching the Ninja 900R in 1984 and Yamaha debuting the five-valve FZ750 in 1985.

Few expected Suzuki, among the more conservative manufacturers of the day, to move the goalposts and, even more, to have put the plans in plain sight. Yokouchi's brave new idea for sport bikes — not to radically increase power but to dramatically reduce weight for improved performance — would appear first in the 1983 home-market RG250 Gamma and then a year later in the domestic GSX-R400. The latter, with a liquid-cooled, 400 cc four, used an aluminum frame, a raceresque half fairing and a seriously aggressive riding position. (Remember that the Interceptor, Ninja 900 and FZ750 had moved just a few steps from the do-it-all paradigm that underpinned all the previous sporty bikes.) The 400 was noted but somewhat dismissed as an oddity, one of many in a long string of "can’t get them here" small-displacement bikes developed for the home market.

Yokouchi, in our interview, framed the argument succinctly: Suzuki was already developing engines close to the agreed-upon upper limit of 100PS (just shy of 100 horsepower) and the newer technology like Honda's V-four engine was adding weight as fast as new material technologies could remove it from the chassis. Moreover, Japanese manufacturers had become enamored of reliability, which would help fuel the rise of their products from post-war "junk" to arguably the most refined and thoroughly developed machines in the world. Harleys still leaked, Ducatis might blow up, but the Japanese machines of this period were known to last and last.

Yokouchi felt that Suzuki had gone too far, that the quest for reliability was making the machines heavier and less competitive than they could be without a change of heart. To prove his point, Yokouchi commissioned a study of the then-current GS750 and had the engineers break one down, literally, and paint each section based on how durable they’d been. Sections that had little to no reported breakage in blue, and those pieces that had seen trouble in the field in red.

"When we brought all the parts together, they were almost all blue! We were building the bike too well; almost nothing broke," he told me. "As an engineer, I say this is wasteful. We have become too conservative." His new mandate, then: 100PS from a 750 cc engine and a 20% reduction in overall weight, which would bring the new model to just under 380 pounds. Most sport bikes of the day were at or around 480 pounds.

Weight reduction by any means possible

Yokouchi managed an effort to reduce the GSX-R's weight on all fronts, chassis and engine in particular. While the bike was loosely based on the GS1000R Suzuka 8 Hours endurance racer, the production GSX-R had to straddle Yokouchi's push for low weight and the ability to produce the thing profitably. Suzuki was a small company then, especially against juggernauts like Honda and Yamaha, so it could not sell the GSX-R at a loss. Suzuki's sales in 1981 reached 500 billion yen, less than a quarter of Honda's contemporary sales.

The GSX-R's aluminum frame broke a lot of new ground, both in motorcycling and for the company. Made up of both cast- and extruded-aluminum members, it was welded in new jigs and constructed of an alloy that didn’t need post-welding heat treatment. In overall configuration it was, however, an evolution of the frame design that can be traced back to the Norton Featherbed of the 1950s: structure connects steering head and swingarm through members that reach both over and under the engine. For the GSX-R, Suzuki widened the spacing between the top members to make room for a larger, freer-flowing airbox and shrank every dimension as much as it could, but it was really a fairly conventional frame rendered unconventionally.

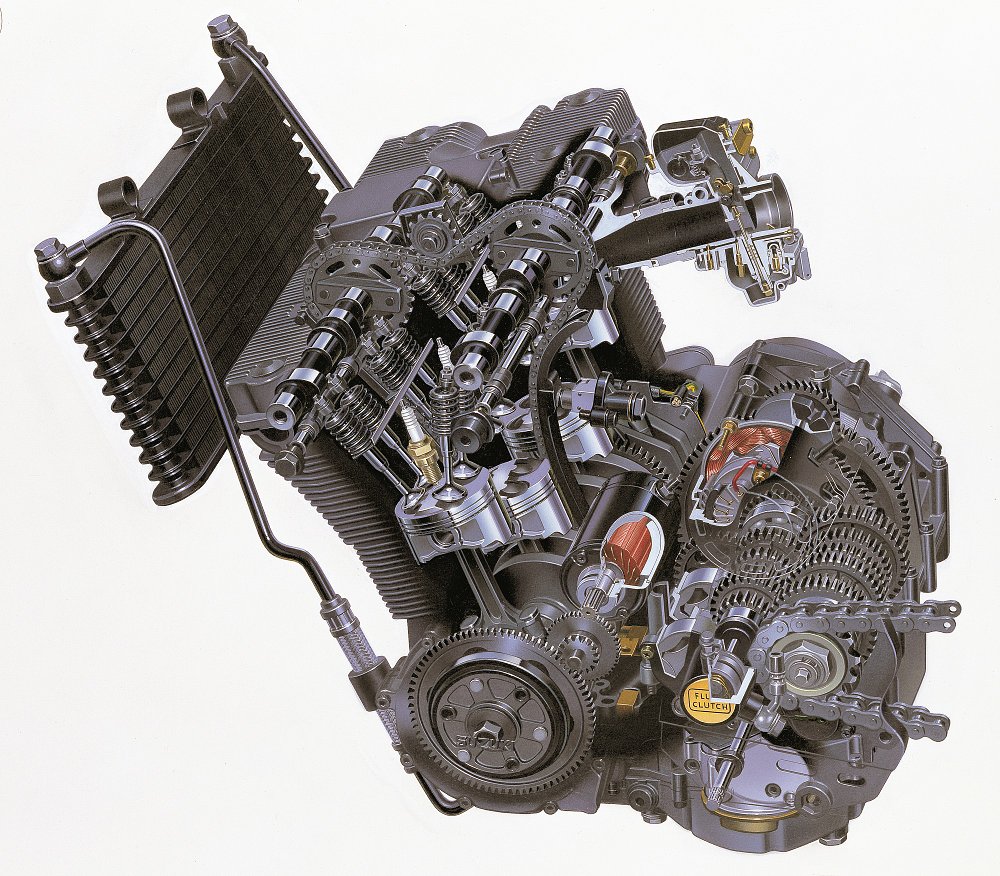

This light chassis had to be matched to a new engine whose dual mandates for power and low weight were dramatically at odds with each other. What's more, Yokouchi knew from his long-running relationship with "Pops" Yoshimura that building a powerful, reliable, air-cooled engine was a daunting challenge, and getting to the 100PS goal would likely create a fragile, top-end-weighted engine as hard to ride as a pure race bike. Liquid cooling, which would come to the GSX-R only years later, was deemed too expensive and heavy, especially with the casting capabilities Suzuki had at the time. And while the company had produced V-fours, the inline four was deemed the only suitable sport bike configuration — for low weight, potential for good power, and the ability to move the engine forward in the frame for better overall weight distribution.

What emerged from Yokouchi's engineering department after an aggressive R&D program that saw many, many engines destroyed in the search for power (without adding weight) was a minor marvel, a narrow engine that used its oil as a supplementary cooling medium. It used an unusual head design where fast-moving oil could wick away combustion-chamber heat. Tightly spaced cylinder fins that recalled aircraft engines of World War II did the rest. It was at once both radical and conventional.

Yokouchi knew something else. He had witnessed the growing interest in more serious sport bikes and heard the clamor from the most vocal proponents that a "racebike with lights" was what they wanted. Management wasn't convinced there was a good business case for it. Yokouchi knew they were wrong, and that a hyper-focused sport bike would not only serve the desires of existing riders, but it could also bring in a whole new group.

The GSX-Risk that paid off

Retelling the development story in 2005, some 20 years after the fact, Yokouchi clearly understood his place in history. He was a risk taker in a company not prone to taking risks, and he was outspoken in ways that were quite uncommon for the time. He understood what standing up for his convictions could do to his career, but he remained steadfast. It was worth the sacrifice: The GSX-R was created from an attempt to catch Honda and Yamaha's technical expansion, but ended up defining the segment.

No motorcycle is the work of just one individual. Yokouchi's team had talented engineers and designers, middle managers with the foresight to let him have some rope, test riders willing to ride a skittish machine prone to breakage and a team in manufacturing who figured out how to make this dream a reality. But you can imagine Yokouchi's voice, emphatic and surprisingly emotional for an engineer, spurring them on. You can imagine the anger in his voice for an engineer proposing adding another gram to the bike, or his enthusiasm for a team member's weight-saving suggestion.

Nearly two decades after that series of interviews, which included many members of the engineering teams, past and then-present, it is that evening in the cold, dour little conference room that remains my most vivid memory of the project.

Etsuo Yokouchi remained true to his vision for the GSX-R. And while it wasn't literally the first factory-fashioned sport bike, it comprehensively reset expectations. Tiny Suzuki made giants like Honda and Yamaha take note and alter course. In less than half a decade, the supersport class would be one of intensely capable and virtually race-ready machines, each owing more than a little to Yokouchi's passionate pursuit of the GSX-R.