Many riders will buy a bike and add some parts to "make it theirs," maybe an exhaust and a few other odds and ends. Poor riding weather can have us combing the net for something that will make our bikes even more enjoyable. I get it. It's a hobby, a passion, and gives a hint of that anticipation we had as children waiting for Christmas to arrive, but now Santa is the UPS driver.

Upgrades can be a slippery slope, however, and in some cases a disappointment. I have seen bikes that have been "modded to death" to the point where they have all sorts of electrical, mechanical, and handling issues, performing worse than the stock version. The economics are terrible, with diminishing returns on investment. In an extreme case, I recently rode a $20,000 sport bike with $80,000 in upgrades and it was clearly worse than the stock version, and the owner felt the same way. Sometimes I liken modifications to plastic surgery — too much can be really bad.

For those who have been following the release of the four-cylinder 2023 Kawasaki ZX-4RR, it's a known fact that the ECU mapping is neutered due to sound regulation compliance issues (not emissions) in the U.S. version. Also, the suspension leaves something to be desired. If there's one motorcycle where interest in modifications is hitting its peak, this is it. Just look at the reader comments on Jen Dunstan's recent comparison of the ZX-4RR and its ZX-6R sibling.

But you want to do the modifications right, and this is where Chuck Graves and Graves Motorsports comes into the picture. Graves Motorsports has been in the racing business for 30 years and has 31 national championships. He put a considerable amount of time and resources into extracting all the performance available from the ZX-4RR. What's on offer is a track-prepped, ready-to-ride version with impressive specs.

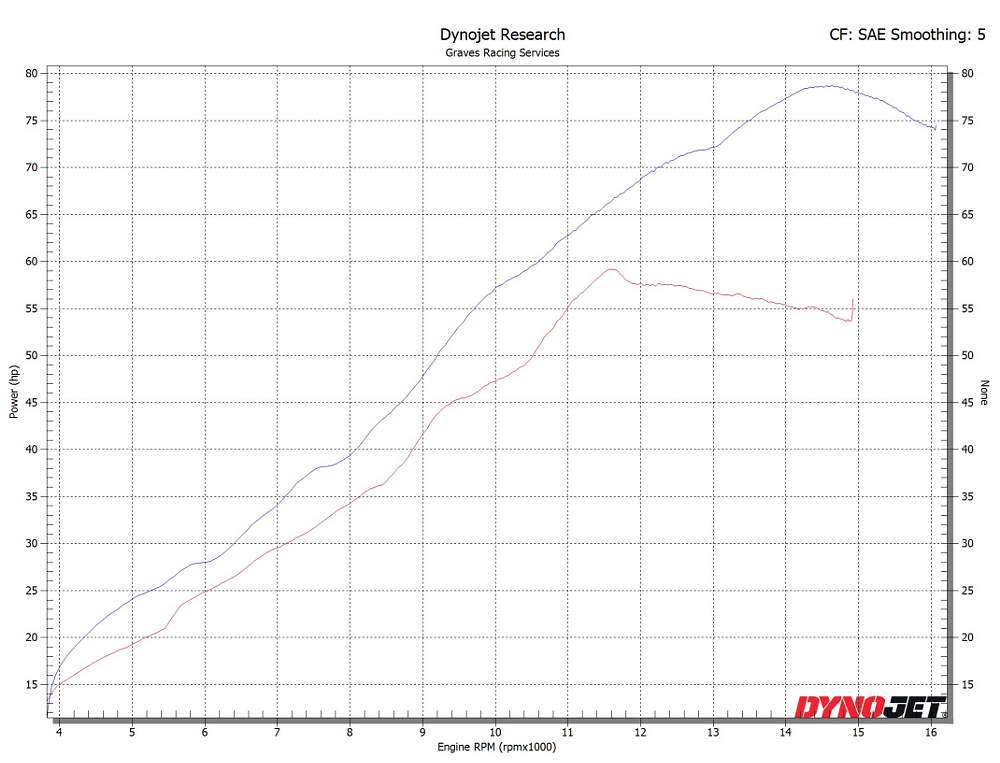

There are three tiers: Track Day ($20,000), Super Track Day ($31,000), and SuperSport ($32,000). You buy the complete bike, ready to ride, not street-legal. All three versions have the new engine mapping and suspension by the Italian brand Bitubo. The similarly priced Supersport and Super Trackday share most of the build specifications. The Track Day version lacks things like the slipper clutch, engine build, and all the electronics and data acquisition featurs such as lap timer and datalogger, suspension sensors, brake pressure sensors, and associated wiring. The SuperSport version is 60 pounds lighter than a stock version (341 pounds versus 401 pounds dry). Additionally, there's a 37% horsepower increase over stock.

Some time ago I was curious how much a full 1,000 cc Superbike build cost and I phoned Chuck. He had a hard time answering because the bike and modifications is the part of the iceberg above the water. What you don't see is all the time in development and R&D.

"Consumers can buy a flash for as little as $350," Chuck said. "A Superbike map cost me $250,000 to develop."

While a MotoAmerica Superbike may cost X amount of dollars for all the hardware, you're looking at way more than that in development to get it working properly. Go to any national level race and at least 75% of the paddock are scratching their heads on how to get the bike to perform and handle the way they want it. There are so many adjustments possible it's easy to get immersed in a pool of unknowns, biases, opinions, and contradictions. Frustrating is an understatement.

Per Chuck, the Graves-spec Kawasaki ZX-4RR is there "to bridge the gap between the haves and have nots by offering factory-level racing equipment and technical support to assist in the use of this equipment." The art, of course, is getting synergy where the sum is greater than the parts. With the SuperSport-spec ZX-4RR, that's what you get.

Riding the Graves SuperSport ZX-4RR

I spent a day at the track with Chuck and the SuperSport ZX-4RR. The experience was unique in many ways for me. Chuck is like the Rick Rubin of U.S. motorcycle racing. He knows a lot about the business and knows how to make a hit, so my interactions with him were compelling. I will explain in a moment.

I geared up and sat on the bike in the pit. Immediate impression: It's roomy. I could easily recommend it for riders six feet and taller, depending on body type. The race bodywork seat is narrow with no-nonsense cushioning in the form of the typical neoprene-type pad. After a brief orientation of the game-controller-style bar-mounted switches, I was off down the pit lane.

Second impression: Throttle response is butter-smooth at initial throttle application. Not weak, just perfectly linear.

Third impression: The quickshifter (works for both up and downshifts) is about the best I've experienced. The positive "click" feel has the right amount of travel and is immediate. I entered the track and gingerly ran the first lap scrubbing in and warming the Dunlop Q5s.

Fourth impression: It felt very stable and planted, not nervous. So many small-displacement bikes feel like toys — KTM RC 390, Yamaha YZF-R3, et al. The Graves SuperSport ZX-4RR feels halfway between a 300 and 600 sport bike, somehow combining the favorable handling attributes of each. I was half expecting it to be twitchy, but it was not.

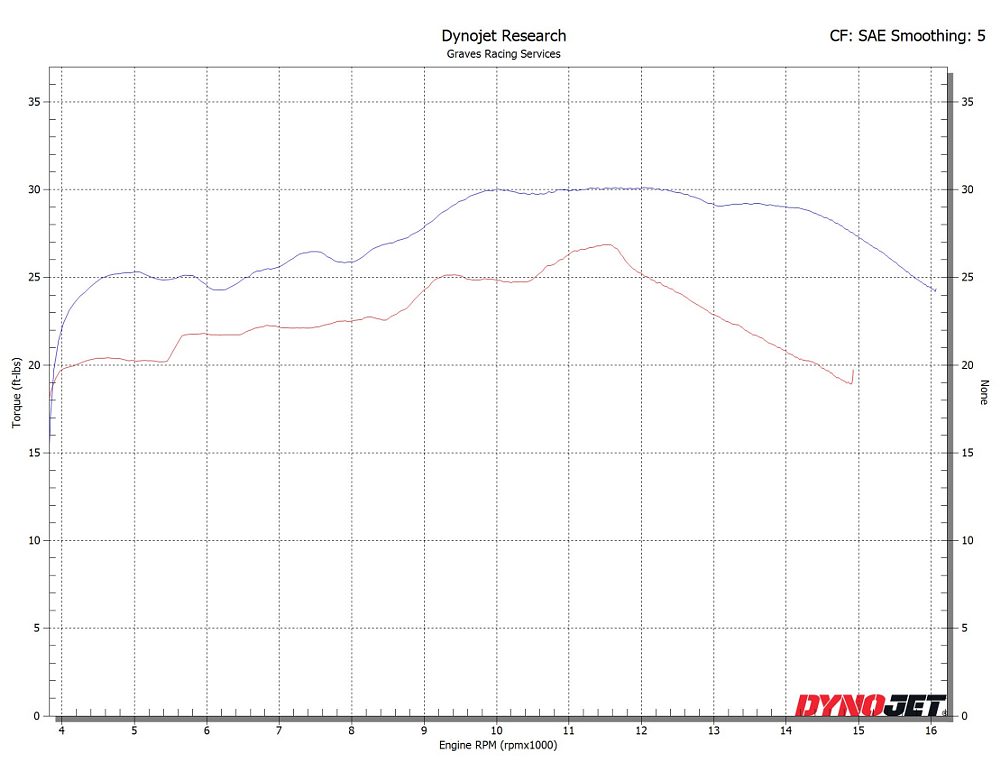

Fifth impression: It's not a fire-breathing monster. At 80 horsepower, it's not anemic, but the motor isn't going to provide second-gear power wheelies coming out of the turns. What you do get is a very linear power delivery with a torque curve that seems to come on rather early versus having to wait until it's screaming to feel a surge. I particularly liked the seamless way power came on in the corners when going from off to on throttle.

Sixth impression: It went where I wanted; it's easy to place on a line. That's no surprise, because it's a typical small-bike trait we all love, but as I mentioned earlier it lacks the twitchy tendencies that sometimes accompany responsiveness.

Seventh impression: It's easy to go fast. After three laps, I started getting down to business, determining optimum gear selection for each corner, throttle roll-off points, braking points, etc. Track riding in my opinion has a lot to do with building a plan or formula matching one's individual speed and capabilities. The triple-clamp-mounted lap timer showed I was rapidly approaching the lap times where my individual talent runs out.

Eighth impression: Throttle roll-ons take getting used to if you ride bigger bikes often. The initial throttle application is smooth and linear, however, maintaining momentum at corner exit requires a rapid twist of the throttle to the wide-open position. This makes sense if you look at the torque curve, which flattens off at 10,000 rpm of its 16,000 rpm redline.

As the pace came up, I noticed a slight understeer in the faster sweeping corners. When I pitted, Chuck asked how I liked it, of course I was complimentary, but he was not interested in getting his ego stroked. He wanted to know what could be better. I mentioned the slight understeer in the sweeping corners, he asked a few other questions and then said, "Leave it to me. Come back in 15 minutes."

At this point, I'll elaborate on how the interactions with Chuck were unique for me. I'm the type of rider who will ride whatever is underneath me, similar to what most magazine editors must do. If there is some shortcoming, I'll change my technique as a "work around." Like a professional race team crew chief, Chuck is all about "making the rider comfortable" and changing things to suit the rider's tastes. He's the kind of person who gives you his undivided attention in a calm yet interested way. He only asks a few questions, with targeted follow-ups, but his demeanor inspires confidence all in itself. This is the first time I've worked with someone who has been crew chief to so many championship winners and I found the experience uniquely fulfilling.

I came back 15 minutes later and rolled out on track again. We were looking for a solution for the slight understeer in the higher speed sweeping corners. Handled, and two more seconds closer to where my talent runs out. However, I did notice that change made the SuperSport ZX-4RR about 10% less responsive when turning into slower corners. I came back in and after a short chat about that, with targeted questions, he said the same thing: "Leave it with me and come back in 15 minutes."

Coming back for the third session, I half expected the slower corner turn-in would improve but we'd revisit the sweeping corner understeer, but instead I got the best of both worlds. The slow corner turn-in and sweeping corner line stability were both there. With these changes in place, I went out for one more session to see if I could improve on my lap times any further, which I did slightly, and in a consistent manner.

Perhaps the most important upgrade is invisible: the tech support. So often we buy something and when tech support is needed it's crickets from the seller and you're left searching online forums or YouTube for help. With the purchase of these ready-to-ride packages, you get free tech support. Every owner is provided with a baseline settings sheet, and any changes from there are noted by the rider. Then there's a software program at Graves Performance that will guide you through changes. For example, if a different-sized sprocket is fitted (making a shorter or longer wheelbase), it will tell you what else to change in the settings to compensate.

Who is it for? Like other bikes I've reviewed for Common Tread, a very small percentage of riders. I imagine it being for track-day riders who have been considering a smaller displacement bike but are worried they'll get bored by the lack of power, young racers moving up the ranks to larger displacement machines, or riders looking for a factory race bike setup at a lower cost. Also, track riders who simply like the idea of a bike that has been optimized by someone with decades of experience, knowing it's unlikely they'd be able to a better job modding their own. I imagine someone who might say, "Make it excellent and send me the bill. I want to know when I'm riding that any problems are the rider, not the bike."

The pricing structure is simple: retail cost of the bike and parts. To frame it favorably, the labor of the build, development hours behind the bike, and tech support are effectively free to the consumer. And as a small bonus, the 400 is much easier on tires than a big bike, so you recoup a little of the money you spent.

If a Graves ZX-4RR fits your budget and profile as a track rider, I have no problem recommending it.