The Honda NSF250R is not the ideal choice for the vast majority of riders in the United States for several compelling reasons: It's designed exclusively for the racetrack, compact in size, relatively costly, lacks an electric starter (and can't be push-started), and demands regular upkeep. However, where it excels, it truly shines.

A few fundamental specifications show why it's a very interesting motorcycle for a few riders, however: a dry weight of 185 pounds, 42 horsepower, and a 28-inch seat height. With ideal conditions, it can go 140 mph.

Editor's note: Dylan Code is a rider coach at the California Superbike School with 26 years of full-time experience in rider training. He has personally instructed 17,000 students across 12 countries. He collaborates closely with his father, Keith Code, on curriculum development and improving the motorcycle riding experience for their students.

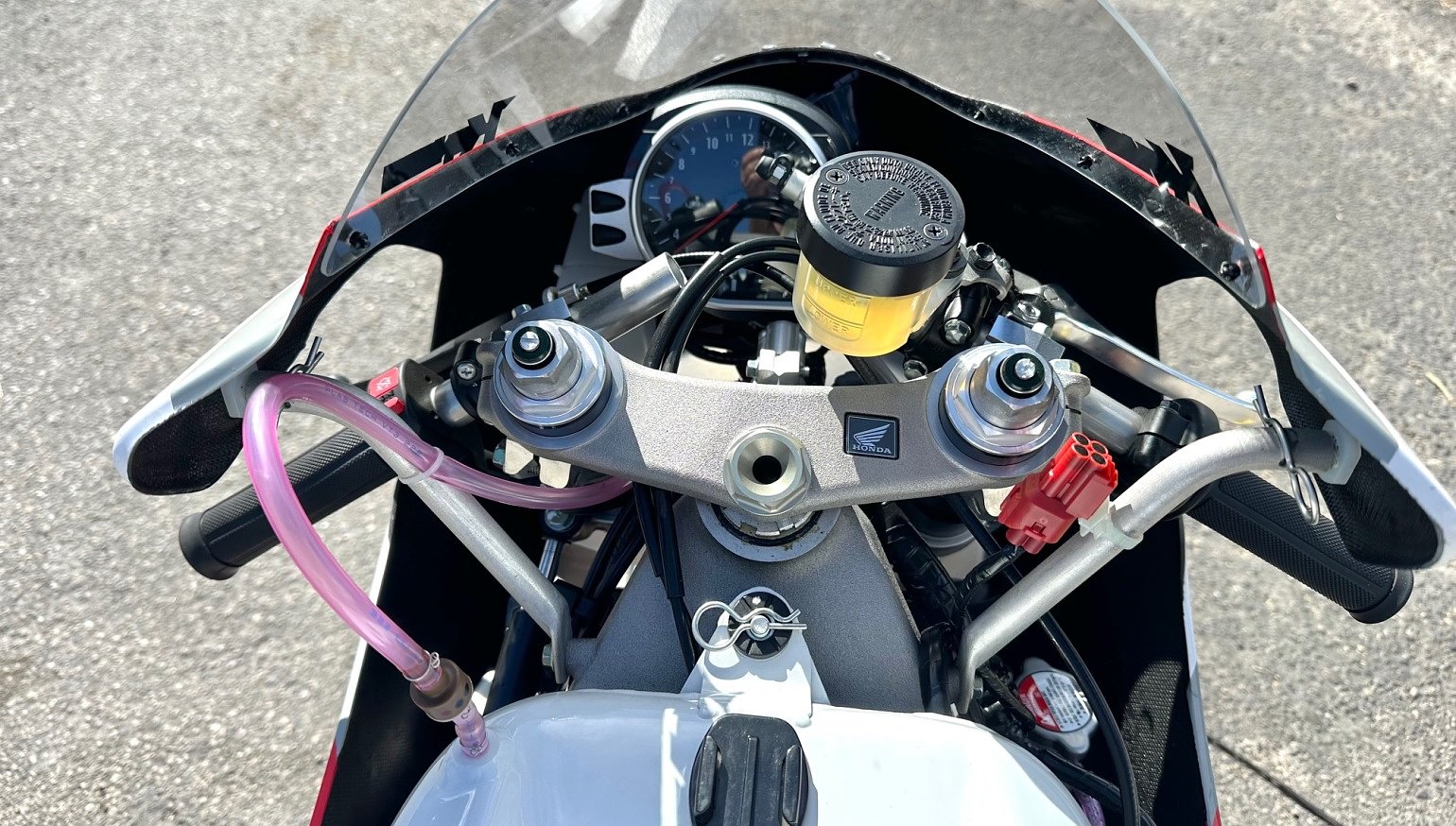

The NSF250R could easily be mistaken for a MotoGP Moto3 bike. In fact, in the racing world it's commonly referred to as a "Pre-Moto3" bike. Pre-Moto3 is an international regional stepping stone for young racers working their way up the ranks in hopes for a chance at stardom at the world level, such as the Asia and British Talent Cups. Despite sharing the same single-cylinder, 250 cc, four-stroke specs, the NSF and Moto3 machinery differ in cost, maintenance, and performance. A true Moto3 bike makes around 60 horsepower, goes 155 mph and hovers around $40,000 used. Honda doesn't export the NSF250R to the United States, but you can buy one from Rising Sun Cycles or Iconic Motorbikes, who buy them directly from Japan. The cost: $13,750. So for about $26,000 less and foregoing 18 horsepower, you can get a taste of what we see on TV in the Moto3 class. Since I had the chance to ride one recently, that's what I thought I'd share with you.

High-rpm echoes of the past

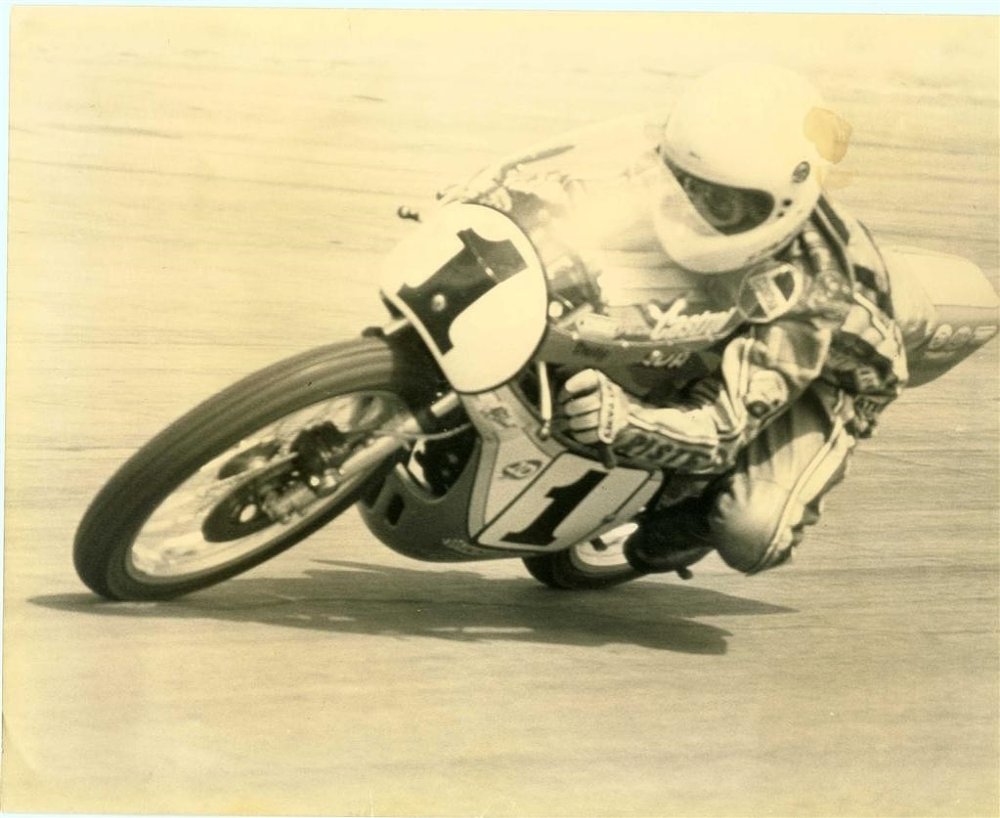

Before we go further, this story has its roots in 1984 when, as a teenager, I had my inaugural encounter with an early factory production racing motorcycle — the Honda MT125. This nimble machine weighed slightly over 200 pounds, boasted 24 horsepower from its two-stroke engine, and could reach a top speed of just over 100 mph. Its engine was derived from the ubiquitous CR125 motocrosser. It presented me with a steep learning curve. The bike generated usable power within the narrow range of 9,000 to 11,000 rpm. Anything below 9,000 rpm resulted in a disheartening gasping and bogging sound, and the engine took an eternity to climb past that 9,000 threshold.

However, once it did, it sharply came to life, sounding like an swarm of angry bees. You had to be quick with the gear shifts because the power disappeared almost as rapidly as it arrived if you ventured past the 11,000 rpm mark. The tachometer needle danced erratically, rendering it virtually useless. I learned to rely on the exhaust note and the sensation of power.

Another intriguing aspect of this and other factory production roadracers of that era was that they didn't feel right unless you pushed them into turns at speeds that street-based bikes of the time could barely handle. If I kept it in the powerband and dived into corners aggressively, suddenly everything fell into place, and I often entered a forced state of "flow": time would dilate, my breathing would slow, and the motorcycle and I would fly down the track in a cocoon of endorphins. It was my first love, leaving an indelible mark and shaping my perspective on all subsequent motorcycles.

Fast forward 39 years, and I find myself at the Las Vegas Motor Speedway, assisting an up-and-coming 12-year-old Los Angeles native named Kensei Matsudaira. As a young racer, I received support from individuals in and around the motorcycle industry, and I feel a responsibility to "pay it forward" by offering coaching and track time whenever possible. Kensei's father, Kuni, recently acquired an NSF250R in preparation for participation in an overseas racing series. Kuni kindly offered me the opportunity to ride it, and how could I possibly refuse? To me, this isn't just another race bike; it's a modern reinterpretation of my first love.

After gearing up and preparing, I faced the initial challenge: starting the bike. It lacks an electric starter and is basically impossible to push-start. The only viable method involves using an electric roller starter, which we didn't have at our disposal that day. So, we improvised by placing a Honda CRF50 pit bike on a pit stand, aligning it with the NSF, both bikes on stands, and touching their rear wheels together to spin up the NSF's rear wheel. Then, in third gear, I released the clutch, and the NSF barked to life.

The ride was an instant throwback to my earlier days on the MT 125, but considerably more manageable in every aspect. The four-stroke engine's low-end power made departing the pits a breeze. The neural pathways established decades ago quickly reactivated, guiding me on how to control such a lightweight bike. The responsiveness to steering inputs on this type of race bike is unrivaled, demanding smooth and precise inputs and rewarding the rider in return with exact compliance. The brakes offered linear, potent stopping power, capable of lifting the rear wheel on demand, with good travel and no fading.

My five-foot, 10-inch frame and size-10 boots, however, presented a challenge. While I technically "fit" on the bike, it felt cramped, requiring me to extend my knee outward to shift comfortably. The bike's narrow build meant that the clip-ons were positioned quite close to each other, necessitating some adjustment time. Nevertheless, the highlight of the experience was the cornering. The entry speeds it could sustain required recalibration. I would initiate a turn, only to find myself on the inside too early. Due to insufficient speed, the bike would dart toward the inside. This pushed me to enter corners with increasing speed, and I half expected it to start chattering or slipping, but to my surprise, it remained rock-solid. The outcome was a big rush through the corners, generating impressive g-forces. Although my 165-pound frame didn't allow for breathtaking acceleration out of the corners, the NSF250R certainly wasn't sluggish, either. The ultimate reward lay in the bike's cornering speed and precision.

So, who is the NSF250R for? I would estimate it's suitable for about 0.0001% of riders in the United States. Clearly, it's tailored for up-and-coming racers, but enthusiasts who frequent track days would derive immense enjoyment from it, as well. I'd recommend it to riders who stand at five feet, eight inches tall and below, and weighing 150 pounds or less. Being a finely tuned racebike, it demands frequent maintenance, including an oil change after every track day or race. The engine requires a major service at 1,200 miles and a complete rebuild at 2,400 miles.

While the $13,750 price tag is not cheap, there's an important factor to consider: This motorcycle needs no upgrades. The brakes, suspension, exhaust, are good out of the box. By contrast, a proper MotoAmerica Junior Cup Ninja 400 build, including the bike, can easily cost $16,000 and does not perform to the level of the NSF250R. Recently, at a track event, I encountered a couple who owned matching NSF250s, and they couldn't be happier with both the bike and the ownership experience. For a tiny fraction of riders, this is close to the perfect track-day or race bike that will put bigger, much more expensive bikes to shame in the corners.

| 2023 Honda NSF250R | |

|---|---|

| Price | $13,750 |

| Engine | 249.3 cc, liquid-cooled, four-valve, single |

|

Transmission, final drive |

Six-speed, chain |

| Claimed horsepower | 47 @ 13,000 rpm |

| Claimed torque | 21 foot-pounds @ 10,500 rpm |

| Frame | Aluminum twin tube |

| Front suspension | Inverted fork |

| Rear suspension | Pro-link single shock |

| Front brake | Dual 296 mm discs |

| Rear brake | Single 186 mm disc |

| Rake | 22 degrees |

| Wheelbase | 47.9 inches |

| Seat height | 28 inches |

| Fuel capacity | 2.9 gallons |

| Tires | 90/58R17 front, 120/60R17 rear |

| Claimed weight | 185 pounds |

| Available | Now |

| Warranty | None |

| More info | hondaracingcorporation.com |