“Listen like you don’t know anything,” Ari advised me.

I just finished loading up the shop van, a task I’d completed for countless other track days. The only difference was this time I was prepping for a two-day ChampSchool.

After five years of track riding, I’d grown complacent. In less uncertain terms, I had plateaued. The rapid progress and enthusiasm that marked my beginner days had receded. So when Ari hurled that last nugget of knowledge in my direction, it stuck with me.

Knowing what I don’t know

I’m slow to the throttle at corner exit. I know that much about myself. A healthy fear of track limits and an unhealthy phobia of high-siding make it so. Like a rule that was never a rule until someone was dumb enough to do it the first time, I’ve been too quick to the gas in the past. It was a mistake that gave me a knock on the head, quite literally. My exit speed has suffered ever since.

To make matters worse, I often compensate for that trigger shyness by maximizing corner speed. Coming in hot on the brakes is the only way I make up the time I lose at corner exit. At least that’s what I thought before enrolling in Champ U.

In 2022, Yamaha Champions Riding School (YCRS) launched Champ U, an online training course that brings ChampSchool concepts to a computer near you. ChampSchool’s pricing and availability are often barriers to purchase. Champ U fixes that problem. It not only makes YCRS more accessible but also serves as a syllabus for in-person instruction. Like any good student, I studied before attending class.

I previously completed Champ U’s Core Curriculum, so in preparation for the two-day school, I focused on the Track Day lessons instead (additional Champ U courses come at an extra cost). The four-part, 163-module course covers everything from paddock etiquette to data acquisition, from on-track safety to tire compounds.

I found the “Slowest Point” and “Learn a New Track” chapters as the most beneficial to my personal goals. In the former lesson, instructors preached the importance of identifying the slowest point of each corner. The key to going fast on track is getting to and away from that point as quickly as possible.

The slowest point also determines the type of corner. Per YCRS, there are three types: entry corners, exit corners, and balanced corners. In simple terms, entry corners contain longer braking zones and shorter acceleration zones. The opposite is true of exit corners, while balanced corners have equal braking and acceleration zones.

These classifications are important because they dictate the proper approach to each turn. You don’t want to approach an exit corner like it’s an entry corner, and vice versa. Therein lied my problem. I attacked every corner as if it were an entry corner. There’s a term for that.

In the “Types of Riders” video, 2022 AMA Junior Cup Champion Cody Wyman role played as an entry-style rider. “I’m always going to be the last person to the brakes. I’m always trying to carry more and more speed into the corner,” Wyman acknowledged before confessing, “I’m struggling with lap times. I’m like 12 seconds off the track lap time”

“Wait, that’s me,” I thought to myself.

I felt attacked. I felt embarrassed. But, I also knew what I needed to work on at ChampSchool.

Not knowing what I don’t know

It’s 7 a.m. The hum of generators fills the air as I roll my Krämer EVO2-690R out of the shop van. The autumnal sun peeks over the distant Sierras. Too bad the forecast calls for a high of 104 F. Fortunately, ChampSchool provides more than enough water and hydration powders to beat the heat. YCRS also feeds each attendee breakfast and lunch on both days as well as dinner on Day One.

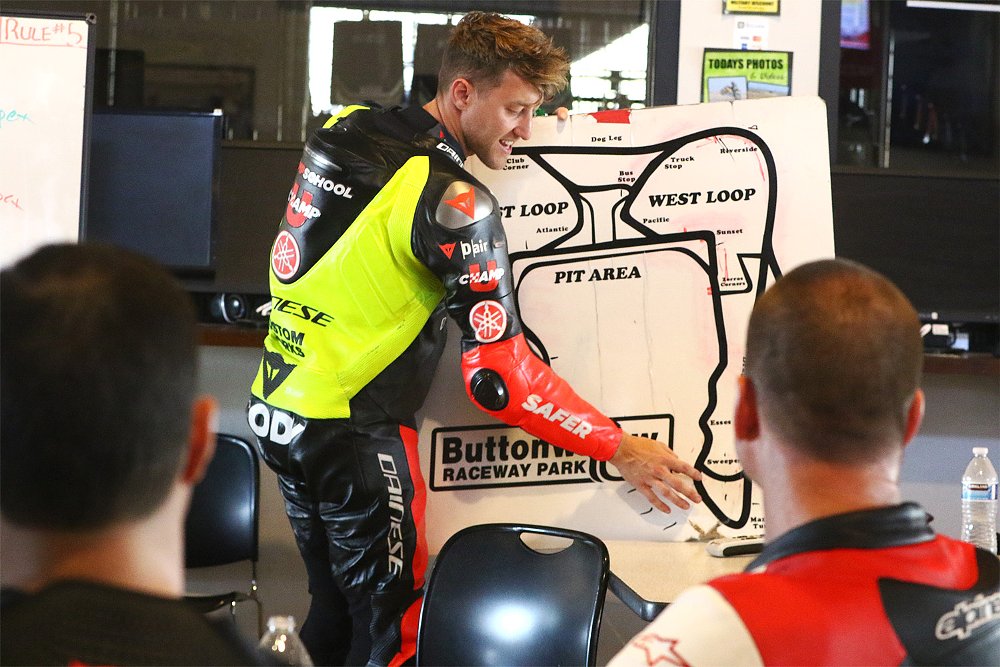

Once the students finished grazing the breakfast table, our group gathered in the paddock to go over ChampSchool’s core concepts. That includes lessons like Focus, 100 Points of Grip, Radius = MPH, and Umbrella of Direction. In summary, YCRS teaches that achieving the proper speed and direction are prerequisites to applying throttle. That’s done, primarily, with the brakes.

By 10:30 a.m., it was time to put that theory into practice on the track. YCRS coaches split the class into several subgroups based on riding experience and skill. While some teams contained as many as five riders, many numbered three or four students. My group consisted of just two riders (me included). That’s a favorable instructor-to-student ratio, no matter how you measure it.

During the first few laps, there was little use in hiding my deficiencies from riding coach, Eziah “EZ” Davis. He instantly diagnosed my late-braking entries and late-to-the-gas exits. “You remind me of a younger me,” EZ admitted. I didn’t know whether I should be flattered or offended. It felt like an insult gift wrapped in a compliment.

Only when my injured ego stepped aside did I see the remark for what it truly was: encouragement. If he once struggled with the same bad habits as me and went on to finish on the podium in MotoAmerica races, I might not be a lost cause, after all. The first baby step on that road of progress required me to look further through the corner.

I often fixate on the apex of the turn. Until I reach that point, I brake as late and as hard as I dare. I may get to the apex sooner but I get to the gas much later. Accelerating isn’t much of an option when nearly all of your 100 points of grip are allocated to braking and lean angle.

By scanning from apex to exit and braking longer and lighter (instead of later and harder), I could set direction and speed much earlier. This allowed me to pick up the throttle sooner. I’d be lying if I said progress was immediate. Breaking old habits isn’t just difficult, it’s uncomfortable. That’s especially true when accelerating sooner and quicker with each lap. Little did I know, I was leaving so much more speed on the table. A two-up lap on the back of EZ’s MT-10 made that abundantly clear.

Riding pillion is only for the brave. I’m used to being in control. Not at the mercy of a wheelie-happy, speed-hungry maniac. At least that’s what it felt like perched on EZ’s back seat. I thought we were low-siding in every corner, endoing in every braking zone, and looping out at every exit. I still have night terrors about it.

At the same time, none of EZ’s inputs were abrupt. That’s because he loaded the tire before “working it.” In non-Champ-School-speak, that means introducing the first 5% to 10% of braking or throttle before ramping up to maximum stopping power or acceleration.

When the lap finally — and thankfully — ended, I knew I was riding nowhere near the limit. I could brake harder. I could lean further. I could accelerate faster as long as my initial inputs were smooth and controlled. This lesson was the key to unlocking more speed, especially with the video lap coming up next.

Knowing what I know

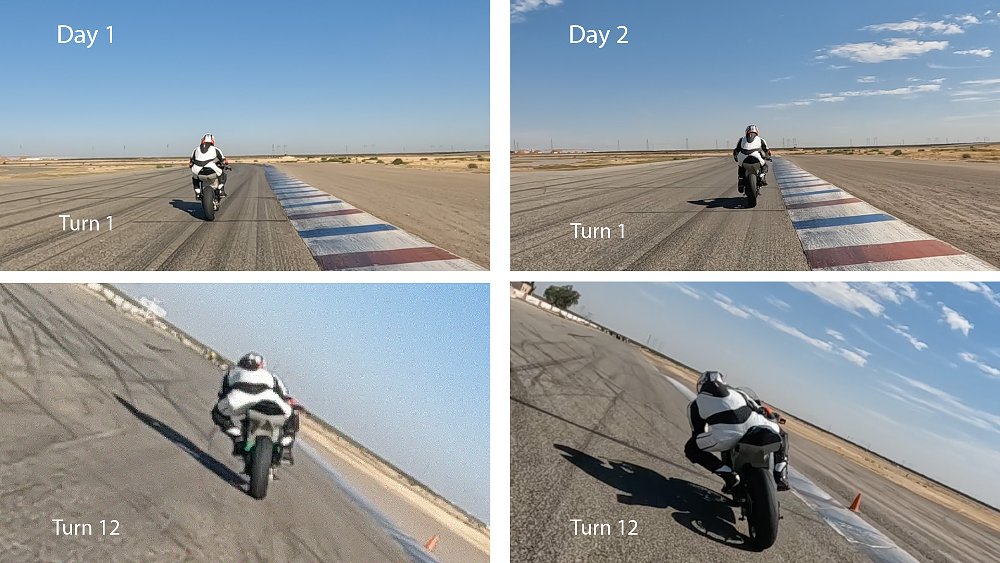

Pictures only go so far when assessing your on-track performance. For that reason, ChampSchool utilizes bike-mounted action cameras. At 30 frames per second, there’s no hiding what a rider is doing, and more importantly, not doing on the circuit. With a coach in tow, I flowed from corner to corner with calm confidence. After all, I was applying the lessons I learned throughout the day. How could I go wrong? Boy, was I mistaken.

Reviewing the footage only uncovered a new issue, and it occurred before I even tipped in to turn one. With my eyes looking further through the corner, I unintentionally drifted inward, off the ideal racing line. That, in turn, shortened my trajectory through the corner and negatively impacted my drive at the exit. Two steps forward, one step back. That wasn’t my only mistake, either.

While on track, I was convinced that I was accelerating to the edge of the curbing. The video revealed a very different story. I often left a bike’s length (or more) between me and track limits. That may seem like a reasonable safety margin but it also sacrifices speed/time in the process. With so much feedback to digest and address, I’d be lying if I said I didn’t feel somewhat discouraged by the end of Day One.

On Day Two, all that self-doubt dissipated when EZ asked, “What’s your plan today?” It was a simple question. It warranted a simple answer: use all of the track. That meant holding my line before corner entry and driving hard to the exit curbing. After a few sessions on track, it was time to prove my progress in front of the camera. It was time for another video lap.

I won’t exaggerate the success of my final flying lap. It was far from flawless. I tipped into turn six too late and rushed into turn nine. I missed a downshift into turn three and an upshift out of 10. I didn’t nail every apex. What I did do, however, is maximize the track. I held my lines and pushed the bike closer to the track limits. But most importantly, I got on the gas earlier and fast. All without the anxiety of high-siding or running off track. That’s something I haven’t been able to say in a very long time.

More to learn

As previously mentioned, the cost of ChampSchool is a barrier for many riders. At $2,495, the two-day class is anything but cheap. Throw in bike and gear rentals if you need them and you’re flirting with shelling out $3,000 in no time. With that said, it’s still worth every penny. My fellow attendees echoed that sentiment. I could sit here and try to justify the four-digit price tag by mentioning the free meals and drinks, graduation goodie bag, and Champ U access, but ChampSchool’s real value lies in its world-class curriculum and brain trust of championship-winning instructors.

ChampSchool helped me address my weak points, but it’s just as beneficial for less experienced riders. In fact, the majority of my classmates were new to the track. Whether you’re a seasoned track rider or just starting out, YCRS can help establish good habits, or in my case, break bad habits. That’s something all of us riders could use, no matter your skill level or experience.

If you do make it to a ChampSchool, I only have on piece of advice for you: Listen like you don't know anything.