Whether you are gay, straight, queer, bi, dyke, or some other flavor under the vast and expansive spectrum of human sexuality and preference, I think we can all agree on one thing: Motorcycles are sexy as hell.

So it’s no surprise that bikes have played such a big part in popular culture as they captured our imaginations and called to the wild side of our inner being. As a bi trans (male) motorcyclist (well, really just a silly little dude on a silly little bike, if I am being completely honest), I began to wonder, as I always do: What does this mean in terms of queer representation? My self-guided research through decades gone by uncovered many iconic moments of queer popular motorcycle culture and history.

Editor's note: See more #pridemoto stories.

The 1950s: What are you rebelling against?

My cruise through the decades begins in the year 1953. Dwight D. Eisenhower was just sworn in as the 34th president of the United States and a man had summitted Mt. Everest for the first time. That was the last production year for the Indian Chief until the brand was revived in 1999 and it was a peak production year for the limited-run Harley-Davidson FL Hydra Glide.

But something else was burgeoning in motorcycle culture, as rebellious American youth became captivated by the silver screen and what became known as the Brando movement. In 1953, Marlon Brando’s film “The Wild One” was released, preceding “Easy Rider” by more than a decade. The film centers on Brando’s character, Johnny Strabler, a handsome Californian rabble rouser who races bikes and gets into tussles with the law and beyond. The echo of the film’s most famous line, “Hey Johnny, what are you rebelling against?” stirred something in an entire generation, especially of underground queers who were lurking fearfully in the shadows. To them, the nuclear family, baby booming world was mostly void of queer representation anywhere. The homosexual overtones in “The Wild One” catapulted Johnny Strabler into iconic status. Maybe gay. Maybe not. One could just imagine, reading ever so subtly between the lines.

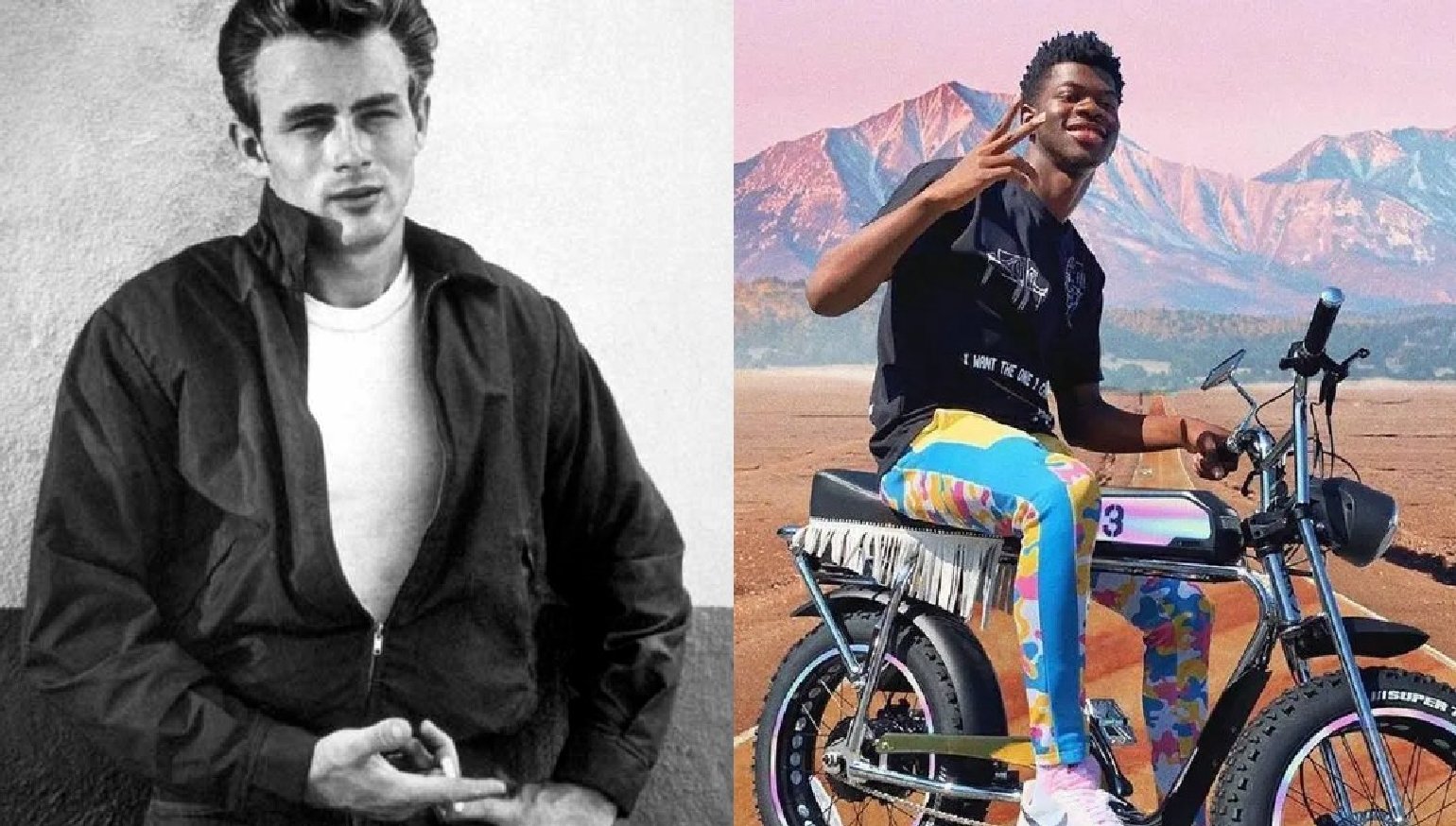

Gay and straight culture alike clung to the rebel imagery the film presented. During a time where anything that deviated from the buttoned-up confines of The Jones’ suburban picket fence was seen as blasphemous rebellion, the hellfire, two-wheeled freedom of motorcycles as the ultimate outlaw status symbol whispered like a tempestuous devil on the shoulder, into the ears of the young, pretty, and bored of that time. Arguably the biggest icon of 1950s rebel culture was James Dean. Dean’s untimely death leaves a lot of mysterious shadows and controversy surrounding his sexuality, but it is widely believed he was bisexual or gay.

Traditionally excluded from outlaw biker clubs, gays began forming clubs as early as the 1950s, with the Satyrs being the oldest known gay MC organization. (Dykes on Bikes, another historically critical activist motorcycle movement, came later in the '70s).

Gay poet Thom Gum described the scene in his 1957 poem, “Man, You Gotta Go” with lines that aptly read:

They ride, directions where the tires press.

They scare a flight of birds across the field:

Much that is natural, to the will must yield.

Men manufacture both machine and soul,

And use what they imperfectly control

To dare a future from the taken routes.

Transgender author/activist Leslie Feinberg’s legendary multiple award-winning queer novel, "Stone Butch Blues" explores 1950s upstate New York through the loosely autobiographical lens of Jess, a fictional working-class transmasculine queer. Jess works in a blue collar factory and rides a hand-me-down Norton that chronically breaks down. Jess describes the bike to friends in an after-hours Friday night scene at Abba’s, a local underground queer bar:

“Something happened to me. I finally felt really free. I’m so excited. I love that bike. I mean, I actually love it. I love that bike so fucking much I can’t even explain it.” All the butches who rode motorcycles nodded to themselves. Jan and Edwin clapped me on my shoulders.

“Things are looking up for you, kid. I’m happy for you,” Jan said. “Meg, set up another one for young Marlon Brando here.”

The 1960s and ‘70s: From upheaval to Stonewall to Leatherman

The 1950s Cold War era quickly gave way to the social uprisings of the 1960s. Lunch counter protests, political upheaval, war, and revolution were thick smoke hanging in the air.

In 1964, queer underground motorcycle leather outlaws finally got the representation they were desperately longing for, in the sardonic experimental film “Scorpio Rising,” by gay filmmaker Kenneth Anger. It’s a 30-minute, completely wordless experimental acid trip of a story about an unapologetically gay motorcycle gang. Trippy Jesus scenes aside, it was ultimately created as a highly artistic and hedonistic love letter to the gay male motorcycle man. The film teems with abject leather fetish homoerotocism. It is a beacon of representation rarely found during a time when gay bashings and jailings were common, civil rights were practically non-existent, and queer culture largely still remained in the shadows. In fact, the film itself was cause for outrage, and as a result, Anger was arrested on obscenity charges. The case went all the way to the California Supreme Court but was ultimately (and justifiably) settled in Anger’s favor.

Meanwhile, in the far different world of international grand prix motorcycle racing, a Canadian motorsport star by the name of Mike Duff was making a mark. Duff burst onto the grand prix scene in the 1960 Isle of Man TT, returned in 1965 and stood on the podium twice. To this day, Duff is the only Canadian grand prix winner in history. Later in life, Mike would at last formally and appropriately become recognized as Michelle Duff. She went on to write her autobiography, titled “Make Haste Slowly.”

As a trans motorcyclist myself, Michelle’s unique history means a lot to me. In a present-day era where some are vehemently trying to erase transgender people, Michelle Duff shows that trans people are with us now, always have been, and always will be.

The tumultuous decade of political and social turmoil ended with a pivotal moment that spurred the modern-day LGBTQ civil rights movement, the Stonewall Riot. One hot summer night in June, 1969, a group of fed-up queers, including two prominent trans women activists, Sylvia Rivera and Marsha P. Johnson, protested a police raid on an underground gay bar in Greenwich Village in New York City.

While the front lines, consisting of mostly brown and black queers, tired of being stuffed violently into the closet, were battling in the streets of the Greenwich Village (and beyond), The Village People, a six-man act co-founded by gay French producer Jacques Morali in 1977, was giving a very public wink and nod to gays everywhere. The group was a NYC disco-fueled expression of gay masculinity, and the openly gay mustachioed motorcycle man persona had finally reached American center stage. Glenn Michael Hughes, aka Leatherman, was no celebrity phony. He was a real deal gay biker known for frequenting The Mineshaft, a gay leather bar in Manhattan (where he drew inspiration for his Leatherman character) and riding a custom Harley-Davidson.

That Leatherman image was captured in numerous works by a Finnish artist known as Tom of Finland, including one titled “The Motorcycle Man.” Tom of Finland moved to Los Angeles from Finland in the late 1970s and was captivated by the underbelly world of L.A. gay leather biker bars. His homoerotic depictions of hunks in tight jeans and open jackets, leaned over black cruisers or café racers, harkened back to the Brando days and could be found in gay bars and art galleries alike.

1980s: MTV and AIDS

If the defiant rebel-without-a-cause attitude of the 1950s was lost in the vibrancy of free love and violent bloodshed of the ’60s and ’70s, then it resurged in the 1980s with leather, hair, and metal. Rob Halford, frontman of British metal band Judas Priest, took the reins as the seedy underground Leatherman of this material-world 1980s generation. Halford regularly incorporated his Harley-Davidson Low Rider into his live shows after getting the idea from some bikers outside a show at a UK club. The stunts sometimes went wrong and he suffered an injury on stage in 1990 after crashing.

Other 1980s queer icon honorable mentions go to Cher and Prince. Cher, a cult gem in the gay community and known for wearing intricate costumes made by gay designers, also regularly donned leather, chains, and chaps as part of her persona. Even as recently as 2020, at age 74, she posed alongside Naomi Campbell and Kim Kardashian in a Brando biker gang-inspired photo shoot. Cher first rode a motorcycle at age 14, and has been known to personally favor the Fat Boy. And of course, while not a member of the LGBTQ community specifically (and in his later years, problematically outspoken against queerness), who can forget Prince atop that customized 1981 Hondamatic CB400A in the Purple Rain video?

The 1980s saw the MTV era and an AIDS epidemic that raged and struck crisis, grief, and sorrow into the heart of queer communities everywhere, as gay men died away in devastating numbers. This tragedy carried on into the 1990s, as did other tragedies, such as the murder of Matthew Shepard in Laramie, Wyoming (among many nameless others). But finally, for the first time, mainstream media cracked open the closet door to allow openly gay and lesbian characters to emerge into the living room television sets of America, arguably paving the way for larger LGBTQ equal rights movements and wins of the 2000s.

At last, in the 1990s, the image of the motorcycle rebels slowly expanded beyond the macho, white, Leatherman, to the boyish swagger and confidence of bold dyke women on bikes, such as k.d. lang on her 1966 Triumph TR6 scrambler custom. “I love the feel of them,” she said in her legendary 1993 Vanity Fair interview and sultry photoshoot with Cindy Crawford. “I love the aloneness. I love moving and seeing things. I like the romance of being on a motorcycle.”

Another gender rebel, though not explicitly out as gay, was Dennis Rodman, who provocatively posed nude atop a motorcycle on the cover of his autobiography, “Bad as I Wanna Be.” Rodman, who famously wore a wedding dress to the 1996 book signing, epitomized self-expression and freedom in a way most Americans had not really publicly seen.

2000s: New representations, out in the open

The technology-fueled 2000s left leather and chains behind with 1990s grunge and the silver screen brought us “The Fast and the Furious” era. Bisexual actress Michelle Rodriguez is arguably both hot and cooler than a bottle of liquid nitrogen, and has been fascinated by bikes since childhood. She is said to possess a huge collection of bikes and rides professionally as a stuntwoman, most recently riding a Harley-Davidson Sportster Iron in 2021’s “F9: The Fast Saga.”

Another professional stunt woman badass celebrity rider is Queen Latifah, who officially came out as a lesbian in 2012. The Queen has been riding her whole life and uses motorcycling as a way to escape the L.A. pressures (and traffic) in the anonymity of a motorcycle helmet. “People don't know it's me," she said. "So I can just rip and run and be at one with myself.” In 1992, just before the launch of her celebrity career, she lost her brother, Lance, to a motorcycle crash. She rides in memory of him, and if you look closely at her character on “Living Single,” you can see his motorcycle key hanging around her neck.

As time moves forward and the young and pretty are more bored than ever, spending their days behind screens instead of behind handlebars, the Brando era still lives on through a new generation of queers who are stepping into the spotlight and re-introducing motorcycles not as a rough-and-tumble lifestyle, but as a carefully executed aesthetic.

Openly gay singer/rapper Frank Ocean famously graced the cover of his album “Blond” wearing a $4,000 custom Arai helmet belonging to a Japanese racecar driver, and a NASCAR hoodie — a thoughtful and artistic reclamation of spaces that have historically excluded queer people of color. Lil Nas X has redesigned the white Western narrative into a defiant and unashamed black gay cowboy in pink rhinestones who rides horses through the hood, and a Super73 electric bicycle through Malibu.

Where will the queer motorcycle aesthetic go from here? That’s unknown. But I do know one thing will always be true. Motorcycles are sexy. And even hotter? The queer outlaw babes who are, always have, and always will be, riding them.