I’m not a gambling man.

The thought of losing my money in a game of chance makes me as anxious as a chihuahua on the Fourth of July. The way I see it, I’m not just losing my pay. I’m also losing the time and hard work required to earn it.

That might explain my ambivalence toward Japanese auto racing.

Quick and dirty

The simplest way to describe auto racing is to call it “flat track on asphalt.” While that analogy provides a broad framework of the sport, it doesn’t quite capture the customs, complexities, or controversies that comprise auto racing. To do that, we have to go back to its beginnings.

The first-ever auto race event was held in 1950 at the Funabashi Racecourse, a dirt track intended for horse racing. (Sounds a bit like flat track, no?). By the early ‘60s, the rising rate of crashes and injuries convinced organizers to hold races on paved courses, with the last dirt venue transitioning to a tarmac surface in 1967. That one change dictated the evolution of all auto race motorcycles thereafter.

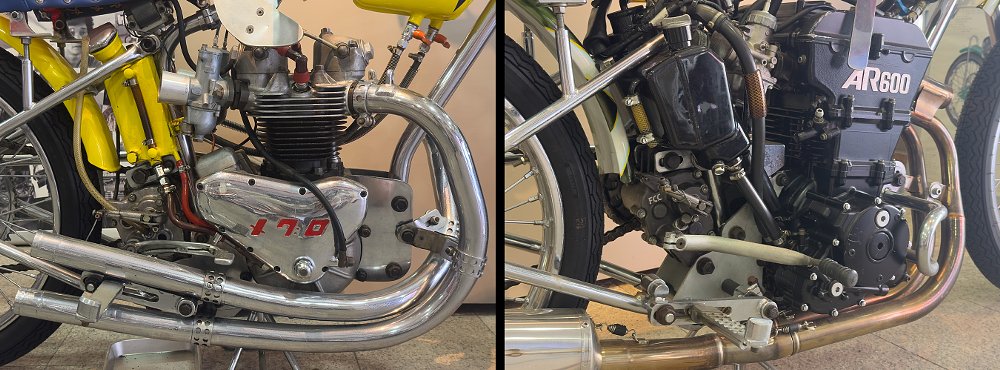

With more grip on offer, speeds and lean angles increased, leading to the asymmetric handlebar designs and peaked tire profiles that still typify auto race machines today. The bikes also lack front and rear brakes (similar to speedway bikes), forcing riders to negotiate each turn with engine braking and line choice alone. Nearly as stripped-down is the suspension. A rigid rear end is the result of a diamond-style frame, while a collection of internal fork springs and external steering dampers suspends the front end.

At the heart of early auto race bikes lived Triumph’s air-cooled, 650 cc T-120 twin. Come the early ‘80s, the Fuji — a series of single- and twin-cylinder engines produced by HKS — dominated the sport. That era was short-lived, though, ending in 1993 when Suzuki introduced the AR600, an air-cooled, eight-valve 600 cc p-twin. Despite only earning a handful of upgrades over the last three decades, the AR remains the mill of choice today.

The ground rules

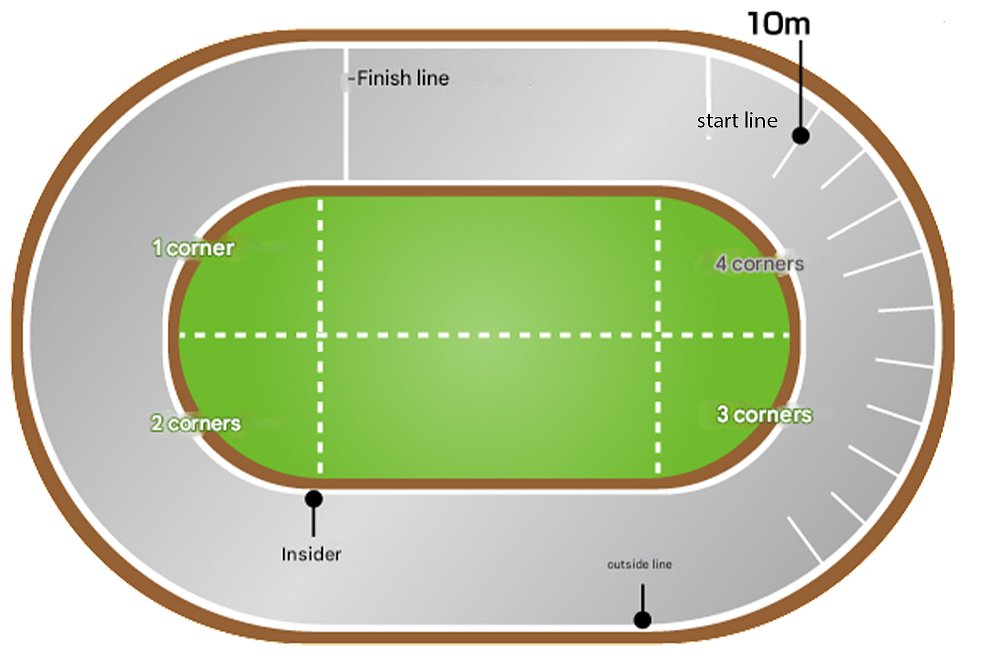

All auto races are held on 500-meter oval tracks, with heat races lasting 6 laps, or 3,100 meters, and championship rounds going 10 laps, or 5,100 meters. If you’re wondering where the extra 100 meters of race length comes from, I’ll direct you to the starting line, which is situated 100 meters behind the finish line. That doesn’t mean everyone starts from the same point, though.

Like Grand Prix racing, riders grid up in a staggered formation. Unlike MotoGP, those positions aren’t determined by qualifying lap times. Instead, most auto races feature handicapped starts, with lower-ranked riders launching from the starting line and higher-ranked riders starting further behind. A series of outer lines, each separated by 10 meters, determines those different starting positions.

Reinforcing that hierarchical rider structure are color-coded jerseys and bike number plates. While the number-one plate may be coveted in most motorsports, it’s reserved for the lowest-ranked rider in the heat. As the numbers rise, so does the racer’s pedigree, with eight denoting the best rider. The number/jersey order follows as such: white (1), black (2), red (3), blue (4), yellow (5), green (6), orange (7), and pink (8).

Auto racing utilizes this system to help the audience identify a rider’s position from the stands. That’s of the utmost importance because auto racing isn’t just a spectator sport, it’s a betting sport.

Beating the odds

Gambling may be a fringe activity for most sports (although it’s becoming more mainstream these days), but it’s the lifeblood of auto racing. The race series isn’t just authorized for public gambling in Japan, it’s municipally operated. Things weren’t always this way, though. As auto race events grew in popularity, so too did the gambling rings surrounding them. With more money riding on each competition, the Yakuza — you know, Japan’s largest organized crime syndicate — started fixing auto race results.

Only after several racers were caught in scandals of the late ‘60s and early ‘70s did authorities step in and seize control. As a result, racers quarantine in on-circuit dormitories throughout the race week, cutting off all communication with the outside world and relinquishing their mobile phones. While that seems like a steep price to pay for sport, the top auto racers are handsomely compensated and hailed as national heroes. It’s easy to see why when watching an auto race in person.

Bet on it

I sit aboard a nearly empty Namboku Line train car, heading north from Central Tokyo. The salarymen and secretaries, dressed in various shades of corporate blue, single-filed through the Nagatacho and Yotsuya exits long ago. Those that remain are the sneakers-and-jeans crowd.

Their hair isn’t sleek and shiny. It’s wavy and disheveled or close-cropped and thinning at the temples. These people don’t spend their days under fluorescent lightbulbs. They don’t live inside budget spreadsheets. Some are graveyard shifters. Others are gig workers or simply unemployed. But most are retirees. It’s a similar crowd at the Kawaguchi Auto Race Circuit.

Tokyo is known for its cleanliness. I’ve grown accustomed to that meticulousness during my months-long stay. That’s far from the case at Kawaguchi. The stands are split between old and less old. Paint peels off the rusty steel girders. On one end, the wooden seats wear a patina that’s somewhere between water damage and mold. At the other end, the plastic seats are sun-baked and scratched. Entire sections of bleachers are fenced off. Repairs should be in order, but there’s no construction equipment to suggest as much.

The only reason I can describe the seats in such detail is because there are so few butts in them. Only a smattering of spectators watch the live show from the stands. Of the attendees in seats, 99% are retired ojīchans. The unofficial uniform seems to call for flip-flops and utility vests. Most audience members are checking their programs or reading previous race results, oblivious to the racers lined up on the starting grid.

The lights go out. All eight AR600s roar to life. It sounds like a barnstormer flying down the home straight. The pack barrels into the first turn, jockeying for position. The white-jerseyed rider clings to his lead, but not for long. The yellow jersey makes a lunge for first. The orange jersey takes the lead one turn later. The blue jersey crashes out. All that mayhem for the pink jersey to cross the finish line first. And. The. Crowd. Goes. Mild.

Much of the audience nods at the result and retreats before the checkered flag returns to its holder. Others simply return to their scorecards. Something tells me that these racegoers are here for the bets, not the battles; for the wager, not the racecraft. The crowds in the betting galleries only support that hypothesis. For every ojīchan in the stands, there are 10 at the odds screens and another five in the air-conditioned theater. Watching several races from these alternative viewing areas told a very different story. A lively one, at that.

There’s the gravelly voice of a charismatic oddsmaker, calling out the most likely podium order. There’s the social dynamics of the theater, with audience members exchanging notes and picks across aisles and rows. It’s a hive of activity. One that I may not fully understand, but one that’s enjoyable to observe. That’s when it hits me. I’m not participating, I’m only observing. The only way to fully experience auto racing is to opt in. It's to put my money on the line.

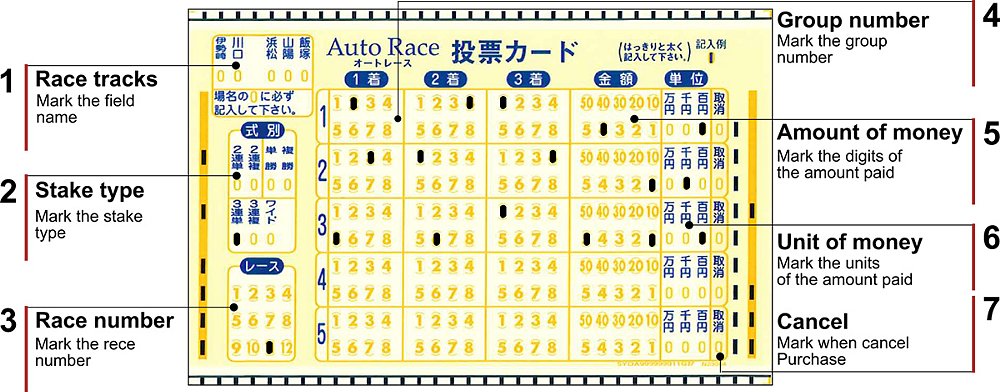

I’m a motorcycle race fan — I’m not a gambler — but auto racing calls for both. So, I study the odds boards, weigh the stakes, fill in my betting card, and submit my picks. I’m ¥4,000 ($27) lighter, but I return to the stands full of optimism only to find a much larger crowd waiting for the race start. (This must be the late risers and fashionably late rush). By no means are the seats packed, but the audience numbers are a considerable improvement.

It’s not just a bigger crowd, it’s a more engaged crowd. Middle-aged ojisans lean over the railings. Groups of ojīchans compare their picks. A female (yes, a female) photographer trains her lens on the starting grid. This time, when the lights go out, a murmur rises, with crowd members pulling for their individual picks. I’m no exception.

I sigh whenever my rider loses a place and rally when they overtake an opponent. I “ooh” when the red jersey throws it up the inside for a pass, and “ahh” when the green jersey gains a place on the straight. I’m one with the crowd. My picks are my own, but we’re all cheering in unison. That’s most evident when the field crosses the finish line and a collective groan issues from the audience. Like everyone else, I’ve lost my money, but I finally understand auto racing. I finally understand gambling.

Studies show that chronic gamblers aren’t chasing the feeling of winning. They aren’t chasing the reward. They’re chasing the anticipation that comes before it. I experienced that same sensation in the Kawaguchi stands. I wasn’t just invested monetarily, I was invested as a fan. I wasn’t just a passive onlooker. I was an active participant. I was a part of the crowd. I was connected. That was a reward in itself. Whether I won or not was irrelevant. Maybe that’s what really draws auto race fans back to the circuit.

Before calling it a day, I placed several bets on subsequent races. Not one of them hit. None. Nada. Nashi. In all, I lost around ¥9,000 ($60). Considering admission was free of charge, that’s a small price to pay for a day full of motorcycle racing. I still don’t see myself a gambling man, but I’ll definitely keep a few thousand yen in my billfold for the next time I head to the auto races.