You've met him at a motorcycle gathering, or a race, or buttonholing you outside a store. “These new bikes,” he says, screwing up his face as if he just stepped in something warm and squishy, “they’re too complicated."

"Back in my day we didn’t need fuel injection or disc brakes. Ignition points and drum brakes were good enough for us,” he goes on, forgetting to mention leaky carbs, asthmatic engines, and kickstart drills that qualified as Olympic events. Give him time and he’ll start in on state-of-the-art riding gear, boasting about the time he rode through a blizzard in shorts and a T-shirt and didn’t even catch a cold.

I have myself reached the age at which men utter such nonsense, but I shed not a tear for the old days, when 1,000 miles was a long way to go between major tune-ups. And while my memory lets me down occasionally (I have actually searched for 10 minutes for a hat I was wearing at the time) I still recall vividly my first motorcycle tour, and my most recent one, too, and though time hasn’t always been good to me, it has made up for it in other ways.

How I traveled back then

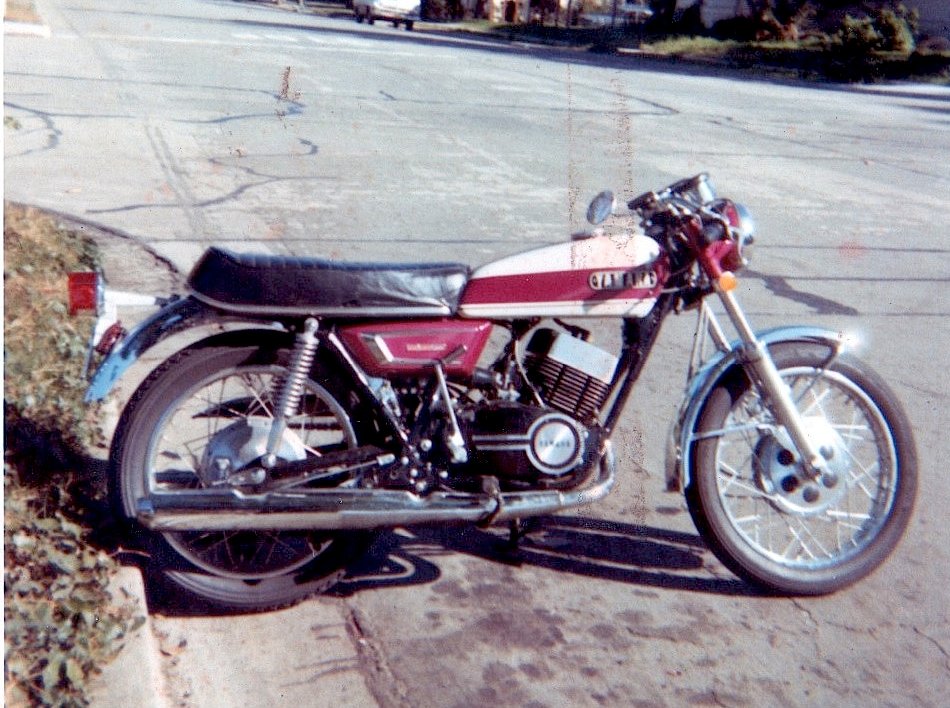

Back in about 1971, when I didn’t know much about motorcycles — or the motorcycle industry, as subsequent events would prove — a buddy of mine and I saddled up our bikes, his a 500 cc Suzuki Titan and mine a 350 cc Yamaha R5, and rode from the San Francisco Bay Area to Los Angeles. The purpose of our trip was to visit the offices of the U.S. distributors of the big four Japanese brands, which had their headquarters in Southern California. We had some fuzzy notion there would be tours on the hour, and exhibits, and test rides on new bikes, and maybe even free key fobs, and we fully expected to return home brimming with tales of glory guaranteed to make us heroes down at the bike shop.

My entire collection of motorcycle luggage began and ended with a pair of vinyl throw-over saddlebags that I bought for $9.95. I lashed them to the Yamaha’s seat with a couple of bungee cords, and crammed the left-side bag full of tools, chain lube, shop rags, spark plugs, a couple of spare inner tubes, (no tire irons, though), and a spare master link. The other side held some clothes, some more tools, some more shop rags, and a quart of Torco two-stroke oil.

What few tools I brought along were chosen in the naïve belief that if I brought them I wouldn’t need them. I had never done anything more complicated than adjusting the chain, and I had yet to accomplish even that basic task without drawing blood. Even if I had known how to adjust the points, I had no tools to do so; I was still struggling with the concept of the spark happening when the points opened instead of when they closed.

The R5 was a fair representative of its time. The front brake was a double-leading-shoe suggestion box that grudgingly supplied stopping power given sufficient advance notice; the rear brake’s job was to keep rain off the axle. The suspension was as finely tuned as a pogo stick’s, and the tires followed rain grooves like a bloodhound after a chain-gang escapee.

My riding gear consisted of a Fonzie-replica leather jacket designed more for impressing high-school girls than for motorcycling; the cuffs, collar, and hem were so loose that at anything over a walking speed the wind blew in and inflated it like a parachute. I had a pair of 20-pound (each) engineer’s boots from The Workingman’s Store, and a pair of buckskin gardening gloves from Orchard Supply Hardware. Blue Levi’s were the uniform of the day for kids my age, and they sufficed as riding pants.

I rounded out my wardrobe with a Buco open-face helmet and Fuji Penguin goggles. When they said, “If you have a $10 head, buy a $10 helmet,” they were talking about the Buco. (After I bought one of the then-new Bell Star helmets I took the Buco up onto the garage roof, put a brick in it, and dropped it off. The helmet survived virtually unscathed. The brick broke into six pieces.) I couldn’t tell you now what I expected to wear in case it rained. I probably couldn’t have told you then, either.

I have no memory of the trip to L.A., not the route we took or any of the stops along the way. When we arrived, we took up residence in a no-tell motel in Buena Park, near Knott’s Berry Farm and right across the street from a Denny’s. As soon as we unpacked we began mapping out the quickest way to each of the brands we wanted to visit. The first one we went to was Suzuki. As we pulled into the parking lot in front of the building, our imaginations furnished it with wonders the likes of which we had never seen in our short, innocent lives.

The astonished receptionist couldn’t decide whether to take us home and feed us a hot meal, or call security. She looked at us like we were a couple of pimply-faced, dumb-ass kids — which we were — and patiently explained that, no, there were no tours. There was nothing to tour, unless we wanted to look at the warehouse, or the accounting department, or the shipping dock, or the employee snack bar, and we weren’t allowed to look at any of those things.

Undaunted, we tried Honda the next day. Same result. Yamaha and Kawasaki, ditto. No dream ever died a harder death. And the hell of it is, we really didn’t care. We took in a half-mile at Ascot. We clomped around Disneyland in our black leather jackets and big boots like a couple of second-string Rockers looking for a Mod whose Vespa we could push over. We were completely on our own for the first time in our lives. We could — and did — have Hostess SuzyQs and Coca-Cola for dinner whenever we felt like it. We had breakfast at Denny’s so many times the cook started greeting us by name. We thought we were the two luckiest guys on the planet.

We took Highway 1 on the way home. The cold wind whistled up the sleeves of my jacket and right through the three T-shirts I had on underneath it — windshields were for sissies. My hands went numb, and my brain nearly stopped working. We made Santa Cruz on the coast and turned inland. The weather warmed up — a lot. Now we were panting like whipped dogs as we crawled along in the sluggish traffic heading back to the valley after a day at the beach, our overheated two-strokes pinging and surging to the summit of twisty, dangerous Highway 17 and down into the Santa Clara Valley. By the time we got home that night we didn’t have another mile left in us.

They don’t make numbers big enough to count all the ways my first motorcycle tour could have gone a lot better with only a little foresight and some better equipment. To my credit, I learned from my mistakes, and over the years I got my touring chops more or less sorted out. I still suffered from the odd lapse of judgment or suffered the consequences of sloppy maintenance, but I was never too far from honing my skills and my equipment to the point of putting in the Perfect Ride.

How we travel in modern times

Then, a few years ago, an automotive website talked Honda into lending me a GL1800 Gold Wing DCT for a road test. Fittingly, the bike was very automotive, and not just in terms of size. The number of features far exceeded what I required of a motorcycle, and even the ones that attracted me to the bike took some getting used to. The DCT in particular was weird at first — my left hand, trained by half a century of shifting gears, kept reaching for the clutch lever that wasn’t there, and my left foot twitched reflexively at the same time — but after trying out all the ride modes I stuck it into Drive and just left it there for the next 2,300 miles.

By then I was a touring pro, with Gore-Tex riding gear, waterproof boots and gloves, and a packing routine I could perform in my sleep. Since the Gold Wing was the archetypal touring bike, I saw no viable alternative but to tour on it. After a week of local riding to become thoroughly familiar with it, I packed the saddlebags, strapped a big duffel bag on the luggage rack, and headed south and west.

In July 2000, I had earned my Iron Butt Association membership by riding 1,023 miles in under 24 hours (the very definition of how not to tour) and shortly thereafter found myself invited to an annual get-together of IBA folks over a three-day weekend in September in the microscopic town of Gerlach, Nevada. I’d been going most years since then, on a variety of bikes (and on one or two occasions in a car) but never on anything as opulent and technically audacious as the GL-DCT (including the car). That the bike belonged to someone else, and that another someone else was paying for the gas, was gravy.

When I struck out for L.A. on the R5, the ink on my motorcycle endorsement was still damp, and it was all I could do to operate the controls without hitting a lamppost; repairing the bike in case of a breakdown was as far beyond my capabilities as designing a nuclear reactor. Now, on the road to Gerlach, there was an order of magnitude more that I didn’t know about the Gold Wing but it didn’t bother me, because I was sure nothing worse than a flat tire would stop it. The dumb-ass kid in the Wild Ones jacket and gardening gloves had learned his lesson, and was swaddled in Aerostich’s finest, snug, warm, and armored against any kind of weather short of a meteor strike, watching the road roll by from inside a modular helmet that cost only a little less than the MSRP of a 1970 Yamaha R5.

During the two-day ride to Gerlach the Gold Wing smothered me with comfort and convenience. It was such an amiable traveling companion that I almost gave it a name. (Passepartout was the front-runner.) The engine was as smooth as a sewing machine, the seat as soft as a sleeping puppy’s breathing. With 125 foot-pounds of torque on tap there was no situation in which the DCT was out of the powerband, and I surrendered control to it gladly. I never realized how much attention I devoted to shifting gears until I didn’t have to do it, especially in an unfamiliar town during the local rush hour. The R5 would have detonated itself into oblivion in the same circumstances and I would have starved to death sitting on the curb waiting for help.

I spent the night in Klamath Falls, Oregon, and took off the next day for Gerlach. By now everything about the Gold Wing was as familiar as my living room, except more comfortable and with better gadgets to play with. I spent the weekend either watching or taking part in wildly irresponsible activities involving motorcycles, firearms, bonfires, and way too much food, and early Sunday morning packed the Gold Wing for the two-day ride home. When I rolled the Gold Wing into my garage, I could have easily grabbed a bite to eat, turned the bike around, and gone back to Gerlach.

This is why you’ll never hear me haranguing some kid about his zoomy new ride, playing the back-in-my-day card like I still miss anesthesia-free dentistry and lead-based paint. To paraphrase Mae West, I’ve ridden new bikes, and I’ve ridden old bikes, and new is better.