There’s a special kind of dread that a rider feels when their motorcycle stops working. About a mile into my first race on Team Obsolete’s famous 1958 Matchless G50, I felt it — the rattle and crunch of an engine eating itself, and the hopelessness soon after.

My earliest memories of the bike I had just ruined go back 30 years, maybe more. I would have been around 10 years old when the Classic Racer Experience VHS landed in our house and I remember huddling around the television to watch Dave Roper’s narrated lap of the Isle of Man TT course. At that point, I had never turned a lap of a race track in anger, while Team Obsolete’s Matchless G50 was already nearly a decade out from its historic TT victory in 1984, with Roper on board.

Never did that boy glued to the TV imagine that some day he would ride that same G50. Much less break it.

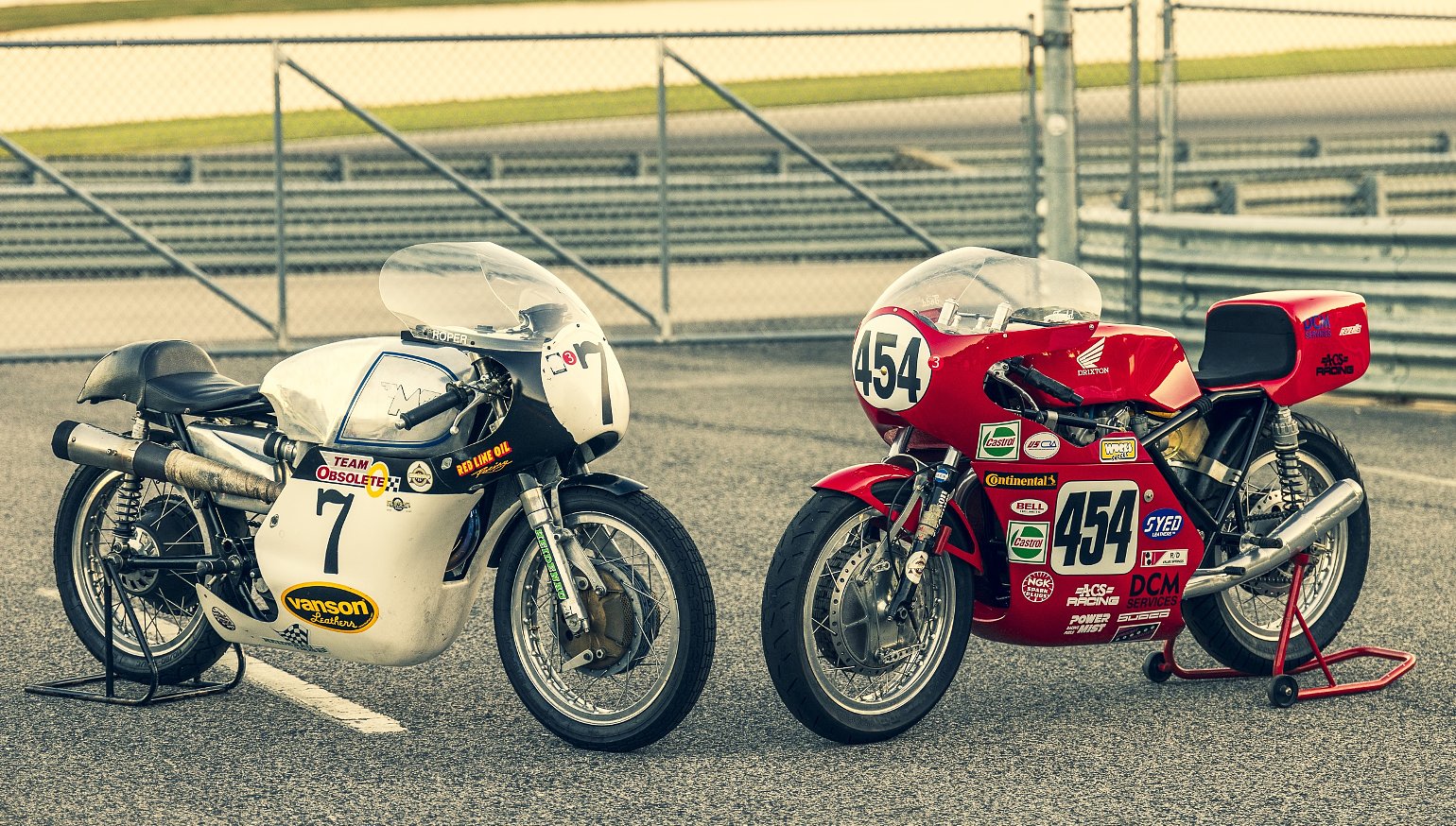

My goal with this famous G50 was much less glamorous but to me, equally important. I was to use this legend of 500 cc Grand Prix racing to play the nemesis to Ari’s dad’s Drixton 450 at the Barber Vintage Festival. We had just spent about a week digging through bins of parts in a barn in New Hampshire and putting back together not just a motorcycle, but a somewhat haunted piece of Henning family history. It was taxing and painstaking for Ari, and the whole team, and it resulted in the most important CTXP we’ve ever made.

As soon as we arrived at the Barber Vintage Festival, however, my role pivoted — I went from helping to holding accountable. We had decided that if we could get the Drixton Honda up and running and ready to race, the best way for me to help revive the honor of the Henning Honda was to race the very machine that Ari’s dad would have had to beat 30 years ago, the Matchless G50.

That plan lasted about six turns until one of the titanium valves — in the “quite-expensive” engine that Team Obsolete had recently installed into the G50 — broke and set off a destructive chain reaction inside the cylinder head. Even if it wasn’t even close to the most emotional thing that happened on our trip, I was disappointed and deflated.

Looking back, moving forward

The irony of the Matchless's breakdown landed the hardest on Rob Iannucci, owner of the G50 and of Team Obsolete. Ever since he hung out the T.O. shingle in 1978, Iannucci’s goal has been to preserve old bikes and let them compete in a condition he calls “honest to their original period.” His relentless enthusiasm for old bikes has led him to add dozens of classic and celebrated racing motorcycles to the stable.

Among them, multi-cylinder MV Agustas once ridden by Giacomo Agostini, at least one Harley XRTT raced by Cal Rayborn, and an ex-factory Benelli piloted by the famous Renzo Pasolini. Also, a handful of Matchless and AJS machines with varying degrees of historical significance. It’s an impressive collection, all tended to within about 8,000 square feet of cast-concrete loft space in Brooklyn, New York, a space Team Obsolete has called home for about 25 years.

“Most of the bikes are in race-ready condition,” says Iannucci. If that seems too ambitious to be true, the 2024 AHRMA race season at least partially backs it up. Team Obsolete ran eight different classic 350 Grand Prix machines in 11 races nationwide, each machine a purpose-built race bike of yesteryear — in other words, no production motorcycles turned into racers.

To have a collection that runs that deep takes many years of dedication, and to hear Iannucci tell it, asking a lot of questions. Throughout his decades of persistence and inquisition he turned over many moss-covered rocks in the motorcycling world. He learned from legendary names like Bob Hansen, Udo Geitl, Don Vesco, Tom Arter, and Dick Mann.

Eventually, Iannucci and Mann collaborated on refining some of Team Obsolete’s collection. Mann had an affinity for the same vein of machinery, especially the G50. “Popular reputation relegated it to second place behind the Manx Norton chassis,” Mann once wrote, “but I felt that you could go equally as fast on the Matchless.”

Their camaraderie led to Mann building a custom frame for a 350 cc AJS 7R in T.O.’s fleet. AJS was an early developer of chain-driven overhead cams, and in the years following the second World War the company kept refining its innovative recipe to broad success. “If you didn’t have a factory bike [in the day],” says Iannucci, “you would be on a 7R.”

Maybe most significant — and completely unbeknownst to the rosy cheeked, 10-year-old me watching Dave Roper fly around Isle of Man on VHS — was what the AJS 7R created. In 1958, AJS wanted its sharpest weapon in the 350 cc privateer-GP world to step up a class, and to do that the company essentially bored out a 7R for use in the 1959 racing season. It was dubbed the Matchless G50.

To look at it another way, Dick Mann’s appreciation and knowledge of the Matchless made his work on any AJS 7R even more relevant. Around the time that Team Obsolete’s G50 conquered the TT’s Mountain Course, Mann started putting together a custom AJS 7R in his workshop in Richmond, California. He used what he knew about G50s, not to mention the knowledge from his illustrious career as a rider, to weld a new frame and attach to it all of the crucial pieces of a good race bike.

When it comes to staying true to the original equipment, everyone’s view on “not that exotic” is a little different. People who know Team Obsolete’s collection might point out that a custom, Quaife six-speed transmission or a magnesium, four-leading-shoe front brake are far from stock. Everyone draws their own line somewhere.

Iannucci’s stance is that his team has done its best not to be tempted by short-stroke engines, electronic ignitions, or suspension componentry that leans too modern — the idea being that the machines should be preserved in a way that still makes them special. And yet here he was, in the paddock at the world-famous Barber Vintage Festival, looking at a useless lump of engine in his beloved Matchless G50 because of a broken piece of titanium.

What’s old is new again

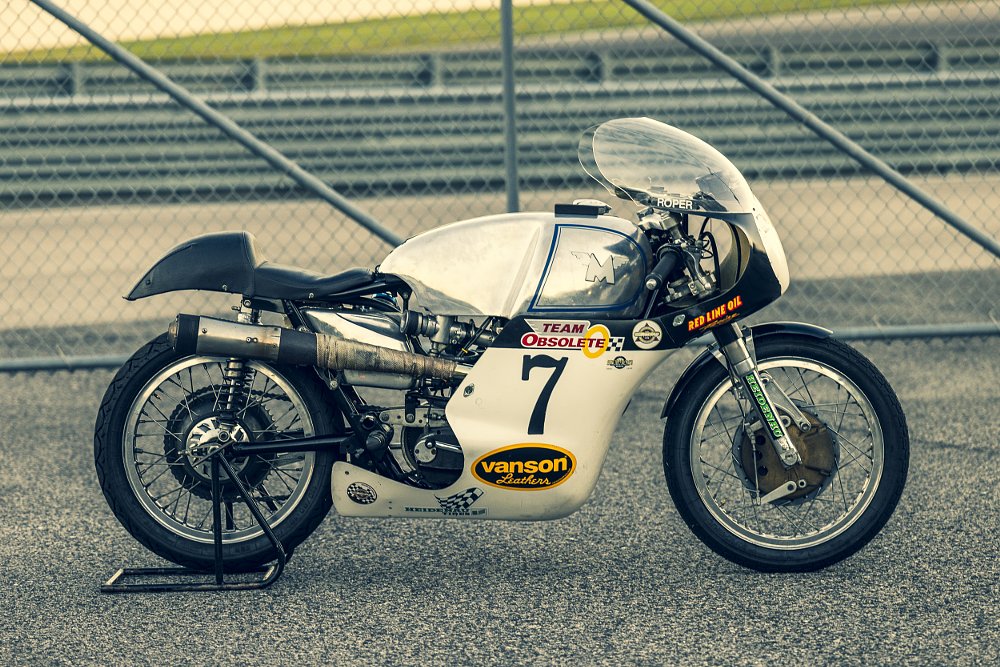

What saved my race weekend and kept the CTXP drama alive was the stricken G50’s paterfamilias — an AJS 7R. The very 7R that Dick Mann built around 40 years ago. Lightweight One, as the bike is known within Team Obsolete, is essentially an amalgamation of notes and knowledge gained over decades of racing and research, including the frame made by Mann himself.

The custom steel-tube skeleton has a steeper steering-head angle, but uses a largely standard 7R swingarm, fork, seat, and gas tank. Some of the added parts are common in the vintage-racing paddock, such as the shocks from Works Performance. Others are a little spicier, like the 210 mm Fontana front brake, reproductions of which cost a few thousand dollars, and this is an original.

The engine, with its characteristic gold cam-chain cover, has been massaged and refreshed over many decades. Bore and stroke are standard, as are the valve angles, but inside lurks a high-compression piston, a custom connecting rod, and a special cam from the legendary Al Gunter.

Peak horsepower is somewhere in the low 40s. That’s a small number in modern terms, but to be fair it matches some of the other specs. Lightweight One’s wheelbase is just north of 55 inches, the seat height is about 29.5 inches, and it weighs around 260 pounds. For context, the wheelbase is an inch longer than a Kawasaki Ninja 500 SE, the seat is 1.5 inches lower, and it weighs 115 pounds less than the Ninja.

Plopping down in the saddle of the T.O. 7R, waiting for the starting rollers to spin, the feel matches the specs. Compared to a modern sport bike the seat is almost comically low and the fuel tank seems long. It’s light, no question, but you might not guess that it weighs 30% less than a late-model wee Ninja.

To most riders it would feel old and clunky and just plain difficult while riding around the pits, but as soon as you start to row through the gears and get up to speed on a race track, Lightweight One finds its footing. It’s a little unfair to keep comparing it with modern machines because the brakes, while expensive, are pretty terrible, and it does not feel fast despite being so light.

Going through turns, though, the thing is kind of magical. It holds a line beautifully and changes direction with amazing quickness and precision, all while feeling stable and composed in all of the ways a rider wants. It makes for a strange mix of sensations — on the one hand, it vibrates like a palm sander and the brakes have virtually zero feel, and on the other hand it offers more grip and cornering confidence than bikes 50 years younger.

What it feels like is a bike made for a racer, by a racer. It is archaic in many ways, for sure, but considering the limitations of the world it lives in, Lightweight One is incredibly easy to ride. It’s a hard thing to quantify. That said, one quick anecdote stands out in my mind.

As I hustled around Barber Motorsports Park bathed in Alabama autumn sunshine, trying to go faster and brake later with every lap, I careened into the final left-hand curve onto the front straightaway with more speed than ever. It was one of those moments entering a corner when you question your judgement, and wish specifically for the tires to hold on. I hung off the bike a little extra, hoping it would be my best lap of the weekend and not my worst moment. As I did, my elbow slider brushed against the inside curb.

I laughed out loud in my helmet. I’ve been lucky to ride a smattering of vintage race bikes from the '60s and '70s, from Honda CB350s and a Ducati 350, to airhead BMWs and a few random two-strokes. Some of them clapped out junkers, others finely prepared racers. Never would I have expected to drag anything other than my knee or my toe, or occasionally my whole body when I tumbled into a gravel trap.

No vintage machine has ever felt as refined and capable at speed as this particular AJS 7R. Which, in some ways, makes sense. On paper, this is one of the most evolved and well tuned vintage 350 GP machines in circulation. The fact that it feels exactly like that shouldn’t be a surprise. Even so, it surprised me.

The race weekend was full of emotion, mostly from watching my friend dig through the difficult and complex history of his father’s long-lost motorcycle. In the end, I didn’t ride quite fast enough to keep the famous Henning Honda honest. What I needed, it seemed, was an AJS 7R with the same sweet handling but with a larger engine. Now that would be the ticket.

From my perspective, it’s a shame I didn’t write my own history with Team Obsolete’s most celebrated Matchless, the bike I remember from the grainy videos and even grainier memories of my youth. Then, I thought about it from the standpoint of the motorcycle.

No machine as noble as a TT-winning G50 would take a failure lightly, I’m sure. Still, it’s a little bit poetic. One of its most acclaimed rivals, risen from the ashes of lingering racing tragedy to ride again, under the gaze of cameras and thousands of spectators — and the mighty Matchless stepped aside.

I’m sure it was only a random mechanical calamity, and nothing more. But that sickening clatter from the engine was, in retrospect, the sound of the G50 delivering me to its origin story. The reasons for its greatness. Maybe someday, when there aren’t more important things at play, the Matchless will show me the more ruthless side of its reputation.