If you were offered a choice between solid brake discs and “floating” brake discs on your motorcycle, which would you choose, and why?

All those answers are accurate, to some degree, but let’s clear the air regarding the differences between solid discs and what are commonly referred to as “floating” discs, which are so technologically superior that the vast majority of modern motorcycles are equipped with them.

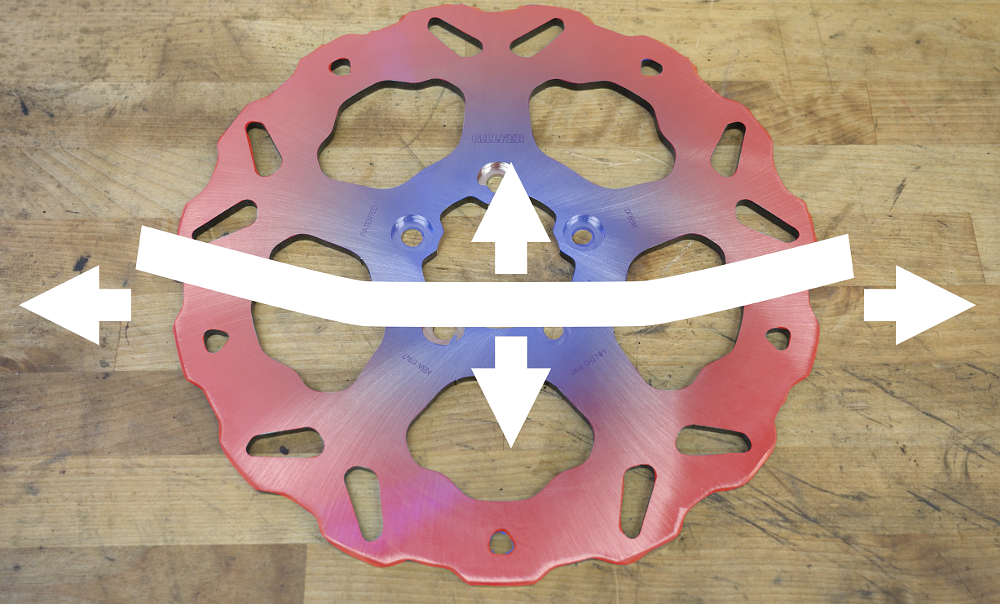

Solid discs are pretty straightforward. They’re a one-piece assembly that’s cut from a sheet of steel. Meanwhile, floating discs have a steel rotor blade and a separate carrier that’s often made of aluminum, and the two parts are fixed together with rivets, which some folks call buttons or bobbins. The rivets maintain an air gap between the carrier and rotor blade, so the rotor is said to “float” around the carrier.

The construction of these two types of brake discs impact their price and weight, and, in the rare instance where you actually have a true full-floating rotor, floating discs improve pad alignment and thus braking power. However, the most significant difference between these two designs is their heat tolerance, and heat is the biggest issue in braking.

When you pull on the front brake lever, the pads in the calipers squeeze the disc, and friction between the pads and rotor slows you down by converting the energy of your forward motion into heat.

As with all materials, the steel of the brake disc expands as it gets hotter. The disc grows in thickness and even more so in diameter, but it doesn’t grow uniformly. That’s because the temperature isn’t consistent across the rotor. The disc is significantly hotter at the perimeter than the center, and that variation in temperature within the disc can cause it to warp or dish. Any deviation from flat and straight will reduce pad contact and make the lever mushy, or perhaps even cause it to pull back to the grip. Yikes.

Now, under hard use on the street, your brake disc might get up to 250 degrees Fahrenheit, which a solid disc can handle without warping. At the track, however, brake temps can be two or even three times hotter than that, which means a lot more thermal expansion and potential for coning.

And that’s where floating rotors really shine. They isolate the hottest portion of the disc from the carrier using rivets and an air gap, and that allows the rotor blade to expand without warping. The separate friction disc is also better at dissipating heat, which helps keep the pads from melting and the brake fluid in the calipers from boiling. Also, by replacing the heavy steel center of a solid disc with an aluminum carrier, two-piece discs are often quite a bit lighter, which is good for all aspects of performance.

As with many performance technologies, floating rotors were originally developed for racing, and in racing applications rotors may be truly full floating. They have an air gap, but the button design also allows for lateral movement so the disc can shift and run perfectly parallel to the pads for better initial bite and brake feel. There’s so much free play between the disc and the carrier that the assembly will rattle as the wheel rolls.

For street use, that amount of movement isn’t ideal for a variety of reasons, so two-piece rotors designed for the street are actually semi-floating, not full-floating. The buttons or rivets that secure the disc to the carrier have spring washers under them to reduce or eliminate the lateral free play seen in full-floating rotors. The design still allows for thermal expansion, so you get the heat tolerance of a true full-floating rotor, but none of the clatter or risk of pad separation, and nobody is going to miss that extra 1% of brake feel and power.

As for solid discs, they were the norm 30 years ago, but now you mostly see them on the rear brake, or perhaps for the front brake on cheaper, less performance-oriented bikes. Modern street bikes, though, are almost exclusively equipped with semi-floating rotors because they offer functional headroom that’s important for safety, because they’re lighter, and because they’re a performance feature that people want, even if they don’t necessarily know why.