Time spent shifting is time the rear wheel is not being powered. Time with an unpowered rear wheel is time lost to a competitor. On a race track, where tenths of a second matter, that's a problem.

That's why race bikes have long had quickshifters — which, as the name implies, make shifts happen fast — to reduce the time the rear tire isn't pushing the bike forward. Sometimes racing technology trickles down to the bikes we ride on the street. Is it really critical to save a fraction of a second when you're accelerating onto the highway for your morning commute? Probably not. But some people like giving their clutch hand a rest, some like the high-tech feel of a quickshifter and probably a few like pretending they're a GP star.

Whatever the reason, quickshifters are showing up on more and more of the bikes we buy and ride, so let’s examine how one works.

Quickshifters come in two varieties. One type assists on upshifts and the other assists on both upshifts and downshifts. We’ll discuss the upshift first, as it’s common to both types of quickshifter. Before we get into them, though, it helps to understand what’s happening mechanically at each gear change.

Normally, on a motorcycle with no quickshifter, the rider closes the throttle. Then the rider actuates the clutch lever to decouple the drivetrain from the engine. Engine revs fall, and once there is no longer power flowing through the transmission, the gears within it are unloaded, permitting the shift dogs to release the gear combo being used. The rider then flicks the shifter to select the next gear, recouples the drivetrain to the engine by releasing the clutch lever, and finally reapplies the throttle.

It takes a long time to type, a long time to read, and a long time to understand, but if you are reading this article, you likely have done it more than once, and you know it’s a pretty quick operation. To cut down the time, though, racers and street demons have long performed the clutchless upshift, which involves rolling off the throttle momentarily to unload the drivetrain, selecting the next gear, and then getting back on the gas.

A quickshifter that assists on the upshift eliminates the needed motion of the throttle. Normally this is done by cutting spark or fuel to the engine momentarily. On carbureted motorcycles, cutting fuel is not practical, so spark cut is the most practical method of interrupting engine power. However, cutting fuel is the preferred method for a variety of reasons, most of which have to do with the negative impact of sending unburned fuel through the engine and catalytic converter, so it’s usually the go-to approach for fuel-injected machines.

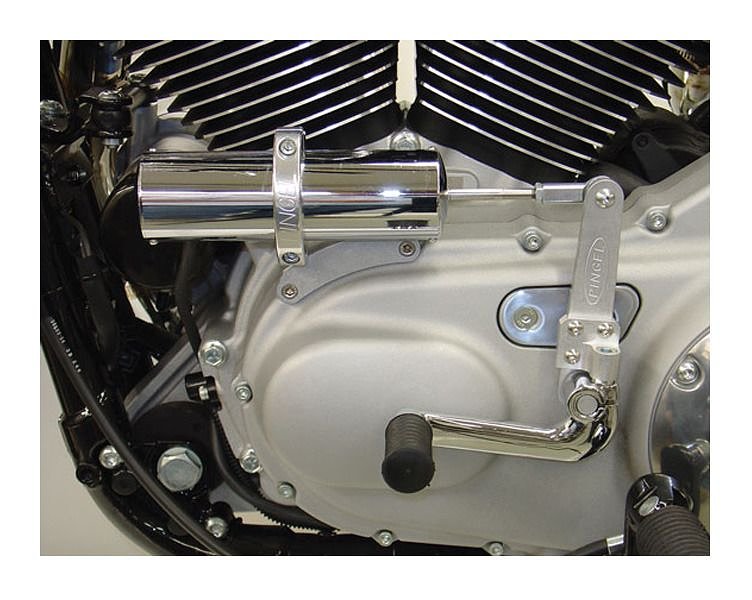

The timing for the interruption is usually provided by a transducer mounted somewhere on the shifter or linkage. (Most common add-on setups run in-line with the shift rod.) The transducer senses a change in pressure on the shifter or linkage, initiating the power interruption for the gear change. Many factory units use a mechanical switch preloaded with a spring at the time of this writing, but switches built with stationary strain gauges exist, which preserves natural shifter feel if the spring thing ain’t for you.

Now, of course, the other half of the equation is the downshift. Not all quickshifters are capable of managing downshifts, because the process is a bit different. You may hear of a quickshifter that also manages downshifts called “autoblippers,” and there’s good reason for that. On a downshift, engine revs don’t need to fall, they actually need to rise. Instead of cutting the engine power for a moment as on a downshift, the engine speed is raised! The engine is “blipped,” as many riders will do naturally when downshifting a gear or two in order to smooth both the engagement of the gear and to help match the speeds of the drive and driven plates in the clutch.

Due to the amount of electronics modern bikes have, like fuel injection and adjustable ignition curves based on knock-sensor input, the addition of a quickshifter isn’t very taxing from either a parts or programming standpoint, so that's another reason they’re becoming more common on factory machines.

If you’ve never used a quickshifter, you should know a few things about them. First, they’re not automatic. You still need to know when to shift and you need to actuate that shift yourself. Second, they tend to work best without human interference, so on the upshift, the throttle needs to be open, and on downshift, it needs to be closed. This runs counter to what many riders have trained to do prior to these units, so that can require an adjustment period.

It’s also important to know these work better in higher gears for the same reason your own shifts smooth out in the higher gears: the ratio jump is smaller as you move up the gears numerically. Furthermore, depending on the quickshifter in question, they can work really well in one part of the rev range, and not so well in the others. Depending on how the units operate, there is sometimes a compromise; not all systems allow all shifts to be silky smooth at all speeds.

Increasingly, you’ll find these as factory offerings on motorcycles that aren’t strictly racing machines — quickshifters have spread rapidly to luxury touring motorcycles, as well. Conventional shifting has some drawbacks, and quickshifters, much like self-shifting motorcycles, attempt to bridge the best qualities of both systems.