I see automatic motorcycles the same way I see M. Night Shyamalan movies.

The same way that no one’s ever told me, “You have to go see ‘Lady in the Water,’” I’ve never heard someone say, “Check out my new Rebel 1100 DCT.” No one I know, anyway. Where are all these people? How do they keep making these things? And therein lies the plot twist. Just like M. Night Shyamalan films, automatic motorcycles are relatively successful.

Almost all of Honda’s Dual-Clutch Transmission models outsell their manual counterparts. The automatic option accounts for around 70% of all Rebel 1100/1100T and Gold Wing sales. Nearly 50% of NC700X/750X purchases are DCT units. That’s boffo bucks, in Hollywood-speak.

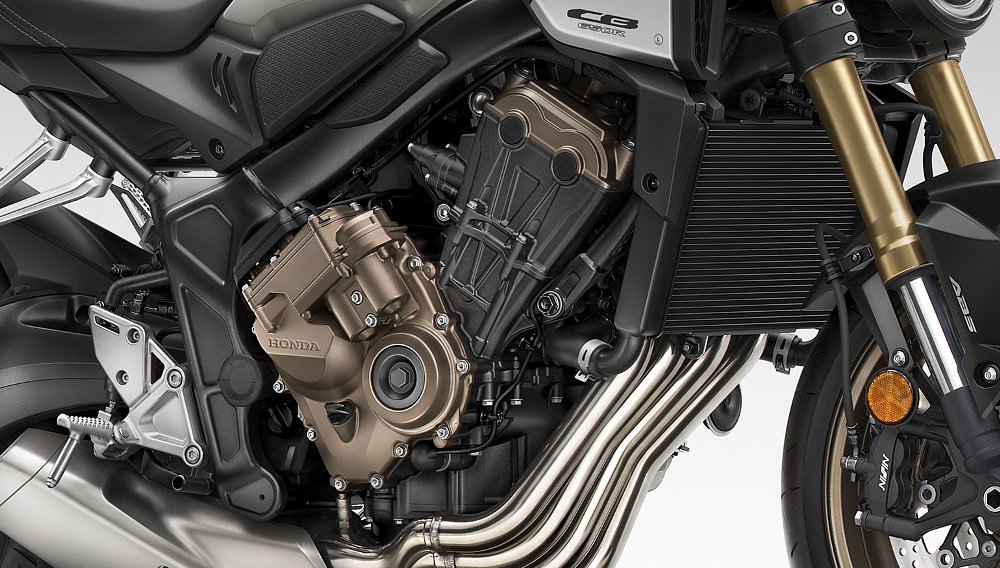

A persistent proponent of automatic transmissions, Big Red introduced several variations over the decades. The Super Cub arrived with its automatic centrifugal clutch in 1958. Who could forget the 1976 CB750A Hondamatic or the 2008 DN-01’s continuously variable transmission (marketed as the Human Friendly Transmission)? Honda sees its new E-Clutch system as a continuation of that lineage.

Despite hailing its past innovations and DCT’s recent gains, the brand also made one thing clear about the E-Clutch — the rider does all the shifting. As Lance noted when Honda announced the 2024 CB650R and CBR650R, the feature is better “described as an automatic clutch than an automatic transmission.” I couldn’t put it better myself. What I can do, now that I've had a chance to use it, is pull back the curtain on the technology, and more importantly, describe how it impacts the riding experience.

How it works

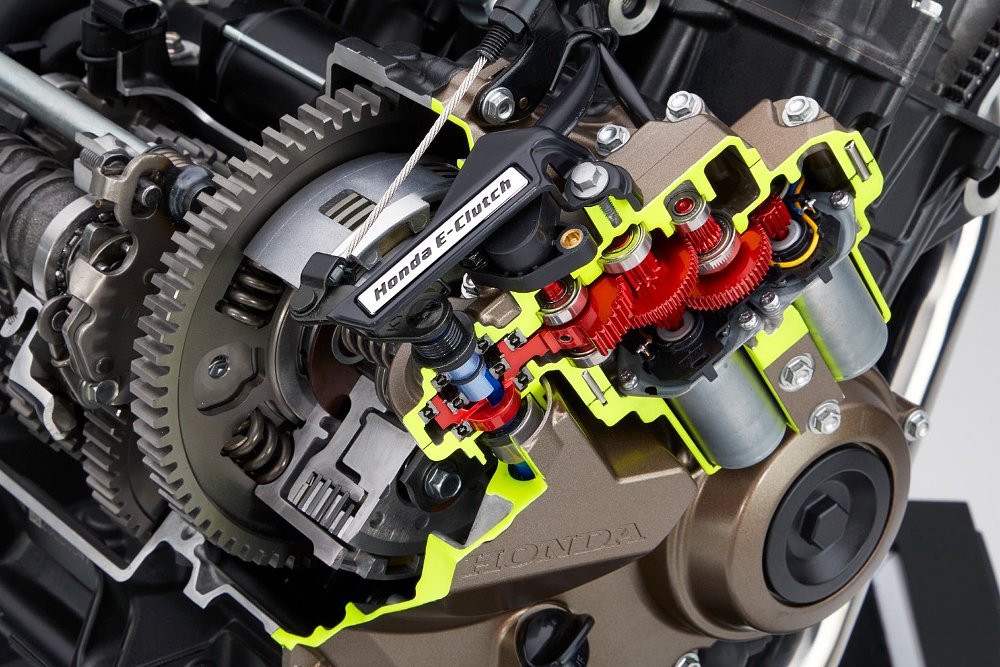

Before delving into the mechanics behind Honda’s E-Clutch, we first need to review the inner workings of the basic clutch system. In an internal combustion engine, the clutch transfers torque from the engine to the transmission, and ultimately, to the rear wheel. The clutch assembly consists of an outer basket, which is geared to the crankshaft, and an inner hub, which connects to the transmission’s input shaft.

Installed between the outer basket and inner hub is the clutch pack, a series of steel and friction plates held in place by a pressure plate and springs. With the clutch lever fully released, the springs and pressure plate force the clutch pack together, connecting the outer basket to the inner hub and allowing the engine to drive the rear wheel.

As the rider pulls the clutch lever in, a cable or hydraulic piston rotates an actuator arm that releases pressure on the clutch pack. This enables the outer basket to rotate separately from the inner hub, effectively decoupling the engine from the transmission and rear wheel. That’s why the rider can prevent a stall or shift gears with the clutch lever pulled in.

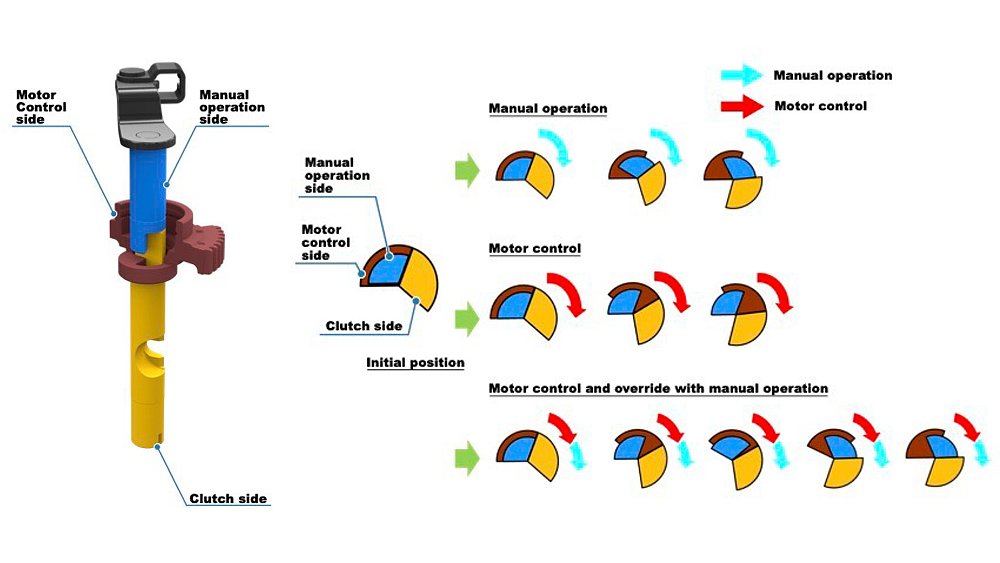

As the critical link between the clutch lever and clutch pack, the actuator arm is the lynchpin of all manual clutch systems. The same is true of Honda’s E-Clutch, except it offers both manual and automatic operation, thanks to a three-piece actuator arm.

Whereas the traditional actuator arm is a single shaft, Honda splits the part into an upper and lower rod. A cable attaches the former to the clutch lever while a push rod connects the latter to the clutch pack. The addition of a motor-driven gear completes the E-Clutch’s three-part mechanism.

Both the lever-actuated upper rod and automated gear can push the lower rod independently of one another. This enables the E-Clutch to engage and disengage the clutch without input from the clutch lever. At the same time, the rider can override E-Clutch’s automatic controls when they see fit. The system even operates like a standard clutch in its full manual mode.

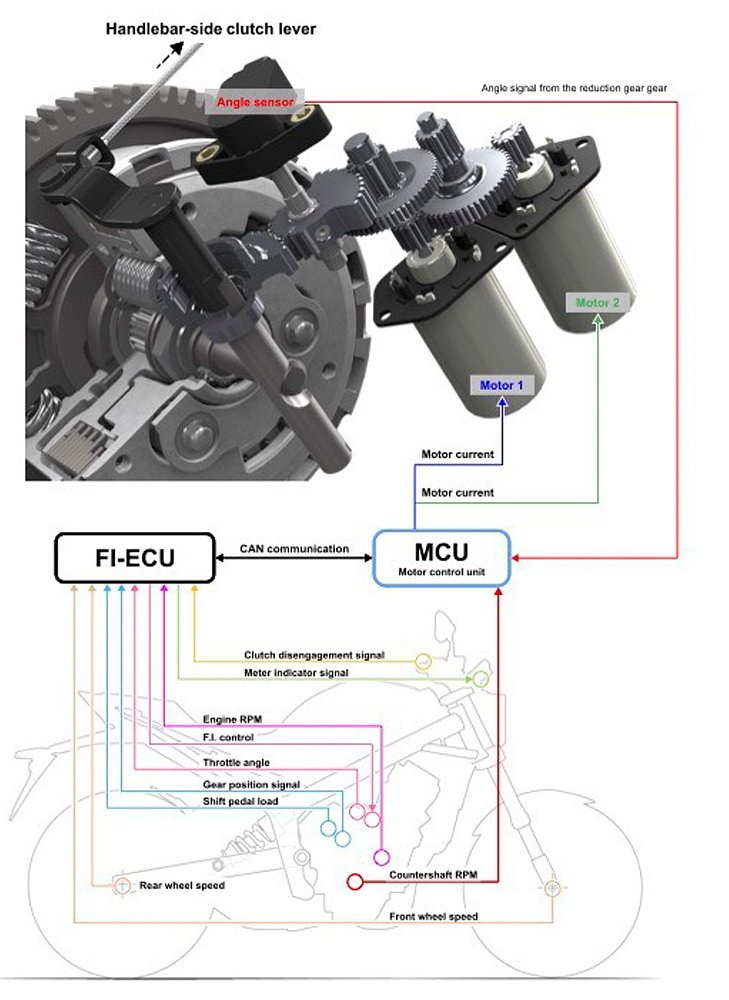

With E-Clutch active, the system’s Motor Control Unit (MCU) collects information from the bike’s ECU (wheel speed, throttle position, engine rpm, etc.), countershaft, and rotation-angle sensor (which monitors the opening between the clutch plates). Based on that data, the MCU activates the E-Clutch’s two internal motors, which drive the actuator arm to compress or decompress the clutch plates at the appropriate time.

Slowing to a stop? E-Clutch automatically relieves pressure on the clutch pack, allowing the engine to idle without stalling. Taking off from a stop, it engages the clutch, leveraging lessons learned from DCT for a “smooth getaway.” At least that’s what Honda claims. To substantiate those claims, I traveled over 2,000 miles to the Atlanta Motorsports Park (AMP) to test the E-Clutch on both the two-mile track and the surrounding roads.

How it rides

Modulating the clutch lever comes as second nature to most experienced riders. Journalists attending the E-Clutch press launch fall into this category. To help us acclimate to the system’s clutch-less operation, Honda held a morning orientation session at AMP. The facility’s skid pad and 16-turn raceway provided a sandbox of sorts, fostering an atmosphere of learning without the pressures of roadway traffic.

After a quick tech briefing, I swung a leg over a CB650R and fired up its trusty four-banger. With its transmission in neutral and its four-cylinder engine idling, it felt like any other motorcycle. Same old same. So far, anyway. That all changed when I shifted into first gear. Without pulling in the clutch (I certainly thought about it), I toed the shift lever down, half-bracing for the worst. CLICK! And yet, the engine just idled along. No bog, no burbles, no burps. That transition may seem seamless, but it requires a lot of behind-the-scenes work.

To complete each upshift, E-Clutch briefly interrupts the engine’s ignition timing and fuel injection, similar to a quickshifter. Before engaging the targeted gear, the system also half-opens the clutch. Per Honda, this “half-clutch control” decreases the shift shock felt between gears, yielding smoother, faster shifts altogether. With the MCU constantly making adjustments based on its data inputs, shifting is also available with an open or closed throttle and at any rpm (including at idle).

But, how does it maintain idle in gear, you ask? Well, upon startup, E-Clutch identifies that the bike is in neutral and opens the clutch plates. The MCU keeps those plates open even after the user shifts into first gear, allowing the engine to idle without assistance from the clutch lever. As soon as the rider rolls on the throttle, the system automatically engages the clutch, enabling the motorcycle to accelerate.

Despite the MCU carrying out countless calculations in the background, the E-Clutch works instantaneously. The slightest brush of the throttle thrusts the CB650R forward. I wouldn’t go as far as calling it abrupt, but it’s more direct than the smooth, gradual starts achieved with a manual clutch.

E-Clutch may go beyond clutch-nursing but it falls short of clutch-dropping. Because the automatic system doesn’t build revs before engaging the clutch, it can’t match the launch skills of veteran racers. That’s the thing, though. Riders can always manually override the system for smooth getaways or race launches. That flexibility is one of E-Clutch’s greatest strengths. It’s even more flexible when the motorcycle rolls to a stop.

Anytime the engine’s rpm falls back to its idle range, the MCU disengages the clutch to avoid a stall — no matter what gear you’re in. As the CB650R approaches a stop, the dash reminds the user to downshift to neutral or first gear. If the rider doesn’t heed those warnings, E-Clutch keeps the engine idling, regardless. That grants the user the opportunity to downshift to the appropriate gear before taking off again. If they fail to do so, the system still refuses to stall out.

In one instance, I shifted up to sixth gear, stopped, and pulled away, albeit very slowly. In no way is that an endorsement of taking off in the higher gears (four through six). I actually warn against it. The engine may not stall but the CB’s acceleration is greatly compromised. So much so that it places the rider in undue danger. I was fortunate enough to test the E-Clutch on an empty slab of tarmac. I wouldn’t want to try that on public roads.

The system’s stall resistance was impressive, no doubt. But, that doesn’t mean it can’t stall. Once the user manually overrides the automatic setting (by pulling in the clutch lever), the E-Clutch remains disabled for a short period of time. If done at high rpm, the MCU re-activates automatic clutch control after just one second. Should the rider grab the clutch lever at low rpm or at a stop, the automatic operation only returns after five seconds pass. During that stint, any stalls are the rider’s responsibility.

Mind you, these are all things I learned before ever leaving the confines of the skid pad. Out on the track, Honda’s E-Clutch is much more performance-oriented.

Through the gears

Speed is king on the raceway. While many see the E-Clutch as a practical feature, Honda was quick to point out its sporting benefits too. Specifically, its clutch-less shifts. I previously explained the system’s upshifting procedure, but the way it downshifts is simple by comparison. When the rider taps on the shifter lever, E-Clutch fully disengages the clutch to release the current gear. Pretty standard stuff. However, the MCU then employs half-clutch control to ease the transition to the lower gear.

Technically, it isn’t an auto-blipper, but it produces a similar effect. That effect was most evident into turn one, where I often dropped three gears in quick succession. Not once did the CBR650R’s rear wheel lock or squirm with E-Clutch activated. I can’t say the same when I switched into full manual mode, as slipping the clutch and matching revs were all down to me. If anything, manually managing the clutch only illustrated the automatic mode’s efficiency and efficacy.

The E-Clutch’s upshifts were just as effortless. According to Honda, the system’s upshifts are smoother than modern-day quickshifters. While I can’t confirm such statements without back-to-back testing, I wouldn’t hesitate to pit the E-Clutch against the most advanced quickshifters on the market. The system’s benefits are most apparent when shifting from first to second gear, where the difference in ratios often expose the less sophisticated quickshifters. No such problem here.

When it comes to shifting, my only could-be-better note concerns the E-Clutch’s sensitivity options. Users can set the shift lever resistance to Soft, Medium, and Hard. To avoid any confusion, that doesn’t impact how the MCU implements gear changes. It only alters the force required on the shift lever to initiate that process. When lapping at a lukewarm pace (we were in street gear, after all), the three settings were nearly indistinguishable. I was either too absorbed with hitting my marks or kicking/stomping the lever too hard to tell.

Only after slowing to a cruise did I feel a difference between the Soft, Medium, and Hard settings. Even then, it was only slight. As I told Honda’s E-Clutch Project Lead Junya Ono, I would have preferred Soft to be softer and Hard to be harder. Otherwise, there's no point in switching out off Medium. In all honesty, I’m not sure the system needs sensitivity settings at all. It shifts so well in default form that I’d probably set it and forget it anyway.

With the checkered flag waving and my clutch hand lazier than ever, it was finally time to leave the safe confines of AMP and test the E-Clutch in its natural habitat: the streets.

Force of habit

Even with hours of practice on a closed course, even after a PowerPoint presentation and a technical briefing, as soon as I rolled the CB650R up to the first stop sign, I pulled in the clutch. With years of clutch lever dependence under my belt, I wasn’t ready to give up the habit. I mean, look at it. It’s right there. Just begging to be squeezed. Now I know why Yamaha, KTM, and BMW ditched the clutch lever with their upcoming automatic systems.

This went on for longer than I’d like to admit. The only times I didn’t reach for the lever was when I actively reminded myself not to. There’s a red light. Don’t grab it. Another roundabout. Just let it idle. We’re pulling over. Don’t — oops, too late. Blame it on muscle memory or auto-pilot, but eventually, I learned to let the E-Clutch do its job. In most cases, it performed those duties flawlessly. I didn't say all the time, though.

I’ll just come out and say it. The E-Clutch lacks throttle finesse. When performing a tight U-turn, the CB often shuffled through its trajectory. The same was true in stop-and-go traffic, where minor throttle adjustments sent the bike lurching forward. In both situations, I typically ride the clutch to steady the power delivery. Fortunately, manual override made that possible with the E-Clutch too. See, not all bad habits are that bad.

It’s worth acknowledging that this is the first outing for Honda’s E-Clutch, and it’s a largely successful one. I don’t doubt that future generations will fine-tune the system’s throttle pick-up, but in the meantime, it’s nice to have the versatility of a manual clutch lever too.

More where that came from

Honda’s E-Clutch is many things. On the track, it functions like a quickshifter and an auto-blipper. On the street, it does all that plus it minimizes left wrist fatigue. Despite all of its performance and convenience advantages, the E-Clutch’s greatest attribute may be its simplicity. Because the system leverages existing engine architecture (and simply changes out the actuator arm in the process), Honda can easily adapt the E-Clutch to other platforms.

I won’t speculate on the models that should receive that treatment but anything that Honda doesn’t offer with DCT or its four-speed semi-automatic transmission (miniMOTOs) are prime candidates. I may not know anyone who watches M. Night Shyamalan’s latest films, I may not know anyone who owns an automatic motorcycle, but something tells me I'll meet someone with an E-Clutch bike in the coming years.