In reality, mileage isn’t that definitive an indicator, or at least it shouldn’t be. Experienced motorcyclists and mechanics will tell you that the odometer reading is only the frame that contains the full picture of the bike’s condition, and in order to fill in the image you need to consider who owned it, what kind of bike it is, how it was used, and how it was maintained.

The previous owner(s)

The bike's past partners play an outsized role in how the motorcycle fared during its existence, since those previous owners determined how the motorcycle was ridden, maintained, stored, etc. For instance, 10,000 miles at the mercy of an 18-year-old is likely very different from that same distance at the command of a retired pilot.

Fewer, more mature owners is always better. Age aside, if someone is the original or second owner, they’re more likely to have taken good care of the bike. Likewise, more seasoned operators tend to a) ride with more moderation and skill, b) adhere to maintenance schedules, and c) have the resources to park the motorcycle indoors.

At the other end of the spectrum is the (often) younger, newer rider who treats the throttle like an on/off switch, doesn’t have much interest in (or money for) maintenance, and doesn’t have a garage, so parks the bike out on the curb, without a cover.

If you have the opportunity to get the seller on the phone or, better yet, meet them in person, you should be able to glean a lot about their personality, which will help color the bike’s history.

What type of motorcycle is it?

A $1,500, 50 cc scooter may be worn out after 15,000 miles, whereas a $26,000, 1,800 cc Gold Wing is just warming up for its first major service. That’s why it’s important to assess the mileage of the motorcycle in light of its classification and caliber.

Some categories simply aren't designed to last as long as others. For example, sport bikes and dirt bikes are, by design, performance machines that tend to experience aggressive use that stresses not only the engine, but also the drivetrain, brakes, and suspension. With proper maintenance and parts replacement, none of that is an issue, but that brings us back to the character of the previous owner. Other bikes that have shorter lifespans include two-strokes and air-cooled bikes, since their engines are more prone to wear.

Then, there are machines such as touring rigs, which often live relaxed, pampered lives as the chattel of the aforementioned mature rider. These bikes have low-revving engines that are engineered for durability, so the 30,000 miles that may be a concern on that Yamaha YZF-R6 are nothing to an FJR1300.

Beginner bikes, dual-sports, and ADVs are other categories that warrant more scrutiny, not necessarily because of how they’re engineered, but how they’re typically used.

How was it used?

Folks worry about mileage because distance imparts wear and tear. But not all miles pack the same punch.

Beginner bikes, for example, can live a tough life and tend to suffer aesthetically and mechanically as the result of tipovers, clumsy use of the clutch and transmission, and neglected, ham-fisted, or botched maintenance procedures. Entry-level models also get passed around a lot, compounding the issues.

Dual-sports, ADVs, and dirt bikes are all designed to be used off road, and if they were, then you can expect the odometer reading to be more consequential. As a rule, motorcycles that are regularly exposed to dirt, dust, and mud (factors that many owner’s manuals designate as “severe use”) are going to experience accelerated wear on everything from the cylinder walls to the clutch cable. Likewise, competition shortens service life due to high revs, intense heat, and severe loads.

For the sake of this article, “use” also includes non-use, such as when the bike is parked or stored. Machines that get to sleep in a garage are better off than bikes exposed to sun and rain. Even the local climate can be a factor — did the machine live near the coast where salty air corroded its parts, or was it preserved by an arid, desert environment? There’s a reason savvy buyers avoid used vehicles from New England, but get excited about machines in Arizona and New Mexico.

Low miles on older bikes may seem appealing, but machines don’t like to be parked. Batteries sulfate, gas coagulates, seals and O-rings dry and harden, and parts rust. A bike that was mothballed properly may be well preserved, but if the bike was simply parked one day 30 years ago, the odometer won't be an accurate reflection of the bike's condition. Or the mileage might be wrong; it’s not uncommon for the cables that drive mechanical speedometers to be broken or missing.

How was it maintained?

There’s a perception that mileage is like the sand in an hourglass. If that’s the case, then maintenance is the magic that lets you shuffle sand back to the upper bulb.

Maintenance and repairs are what really determine the effect of the mileage on the odometer, so investigating how a bike was taken care of is crucial. A seller who produces detailed notes and a stack of parts and service invoices is the gold standard, but sometimes there’s no recorded history and you have to make an assessment.

A quick look at the drivetrain is the easiest way to get a general idea of how much TLC a bike has received. After all, if an owner is willing to ignore a component that you can see, hear, and feel needs attention, what do you expect their stance to be on out-of-sight components like the air filter?

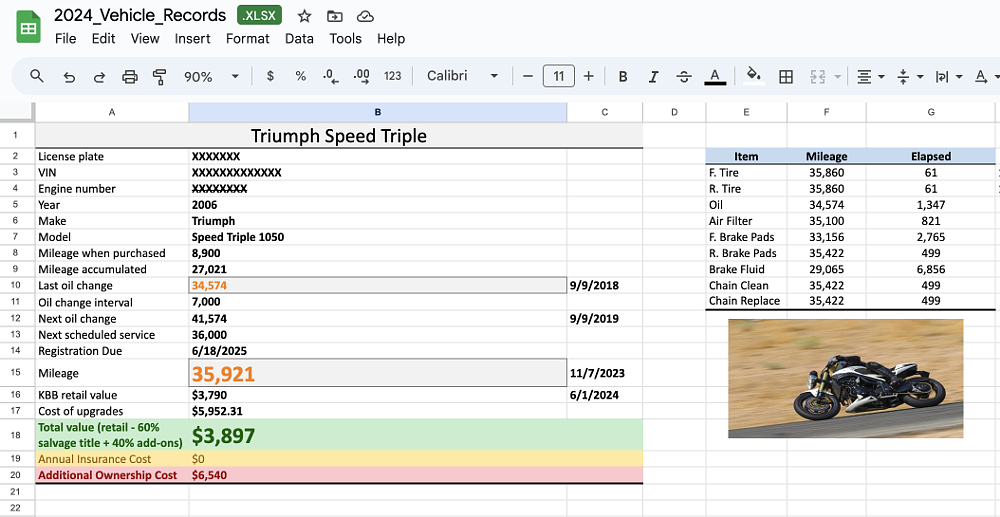

And while I’ve spent all this time encouraging you to think of mileage as a factor in an equation as opposed to an absolute number, the odometer should be taken at face value when it comes to the maintenance schedule. When shopping for a bike, it’s smart to familiarize yourself with the schedule for larger, more difficult (and thus potentially ignored) services like spark plugs, air filter, and valve clearances. Find out when these services are due, and inquire about whether they've been done. Some owners opt to sell a bike once it approaches a major service so they can avoid the cost, or they might just be ignorant. In either case, knowing the service milestones is important for assessing the condition of the bike and identifying any upcoming (or past-due) expenses that could tip the scale of the deal.

It’s just a number

If mileage is viewed as a countdown (countup?) to a bike’s eventual demise, then concern about buying a bike with too many miles is that crucial components like the pistons, valve train, and perhaps the transmission will be worn out and not function properly. These are realities if a machine racks up enough miles, but to be fair, most motorcycles manufactured in the last 30 years are made well enough that as long as the oil is changed on time, the engine will likely outlast the rest of the bike.

The more likely issues with what people call “high mileage” motorcycles are things like a worn-out drive train, bald tires, gritty wheel bearings, thin brake pads and discs, and perhaps leaking suspension components. This is really just deferred maintenance on consumables. So if you’re willing to go through the bike and replace everything that the previous owner ignored, you could end up with a machine with a long service life ahead of it.

Ultimately, mileage is fairly subjective. For someone who has a tub full of elbow grease to dispense, mileage might not matter, because the bike is going to get fully rebuilt anyway. Meanwhile, if you want a motorcycle that’s ready to ride and will be reliable, you’ll likely be looking for something fresher with a known history and up-to-date service records.

The key is to be aware before you buy, which is why it’s so important to look past the odometer to the rest of the bike, its owner, use, and maintenance, so you can get the full picture of the bike’s condition.