How much complexity is too much on a motorcycle?

I imagine every rider in the modern era has pondered this. It's been hashed out right here at Common Tread before, at least as it pertains to the technological aspect of motorcycles. The author of that piece wrote something that I found interesting. "Of all the bikes I tested last year, excluding e-motos, Ducati's Multistrada 1260S was at the furthest end of the digitization spectrum. Indian's Scout Bobber was the most mechanically traditional… aside from fuel injection, ABS, and a small digital clock and gauge slot on the needle speedo, it's sparse on tech options. There's no app or USB on this one."

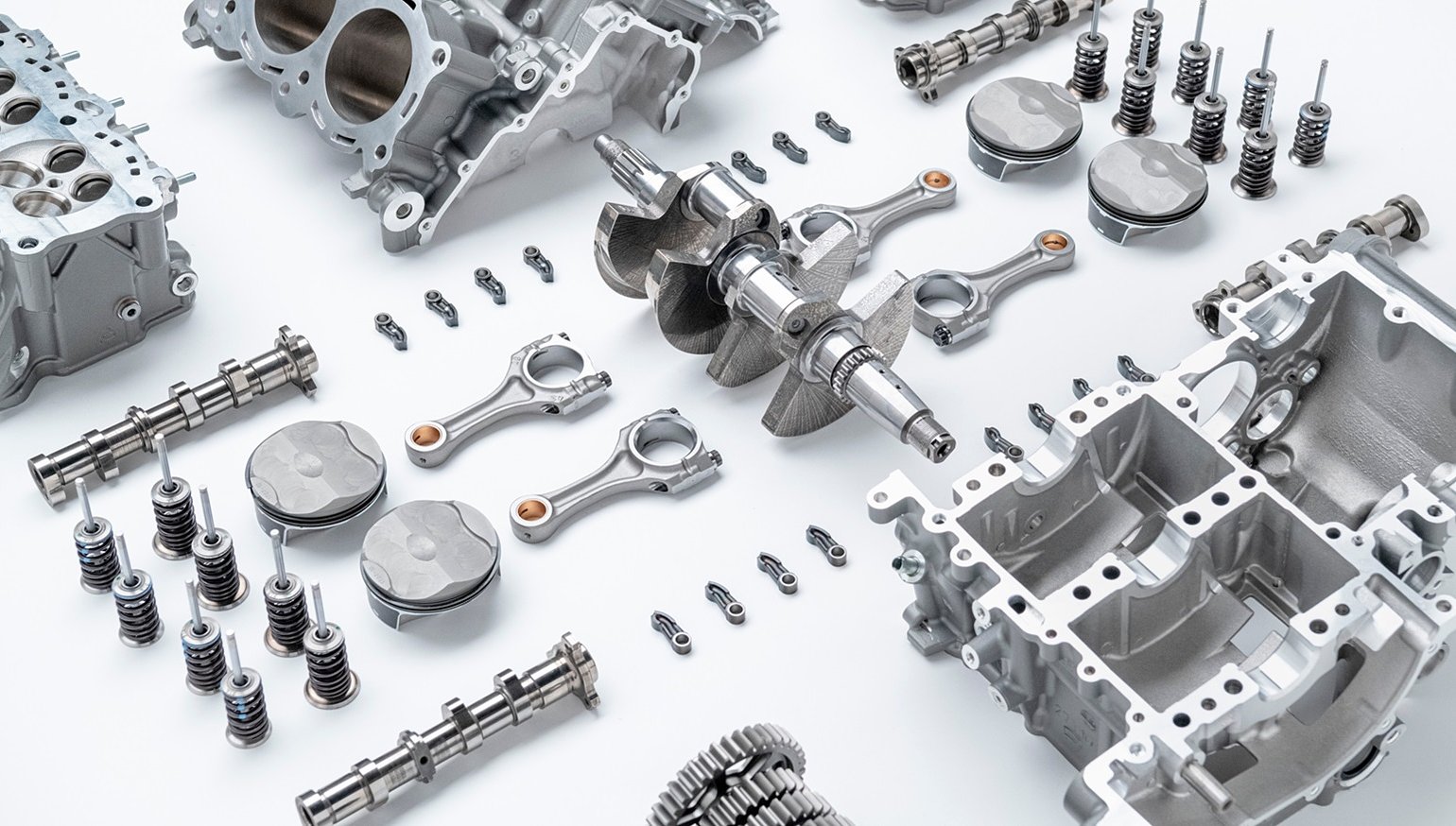

I understand perfectly well what Jake is saying here. The ride is uncluttered. There's one clock on the bike and not many buttons beyond what you find on a learner bike. But the Indian Scout is actually a modern marvel of mechanical sophistication. It has a starting module that not only makes use of dead revs, but also electronically disengages the starter after it senses that the engine has started. Its liquid-cooled engine features a four-valve-per-head-DOHC engine with shim-under-bucket valve adjustments, the same as you will find in many top-level competition machines. The motorcycle has two cam chains, two hydraulic tensioners, four cam gears, and four cam chain guides onboard.

This design nets the owner a maximum claimed 100 horsepower and 72 foot-pounds of torque. Credit must be given where it is due: 100 horsepower from a 1,200 cc twin is compelling. It wasn't so long ago that 100 horsepower from a twin was the domain of very seasoned tuners who threw reliability to the wind in pursuit of that level of performance. Indian achieves it and throws a warranty on top.

However, all those valvetrain parts I rattled off add up to a valve check that appears to be worth about six hours of shop time, with a street price north of $1,000 at the time of this writing. And that's assuming the valves are within spec. Any adjustment will cost quite a bit more. Gone are the days of the screw-and-locknut adjusters where checks and adjustments happened at the same time for basically the same amount of labor. No, these Scouts, like many modern motorcycles, require measurements to be taken, like all bikes. But if adjustment is needed, cam removal and special-order shims are the order of the day, because there are many sizes and stocking all of the possible combos would be prohibitively expensive. (Five years ago, I remember being horrified at a similar cost to check 24 of the BMW K 1600 B's valves, too. Still haven’t gotten over the sticker shock, I guess, especially when the same amount of dough gets you just eight checked in 2023.)

In defense of Indian's engineers, it's highly likely the valves will not need adjustment — not just at the first service, but maybe even never in the bike's expected service life. But the checks must be done, nonetheless.

And that's not to mention the software

Some of you may be aware of some of the right-to-repair (R2R) legislation that has become a battleground recently. Vehicle manufacturers have made accessing repair information difficult for independent shops and mechanics. Nominally, this is to keep unauthorized users from accessing and controlling the vehicle and preventing tampering with systems like emissions.

By way of example, when performing diagnostic scans on, say, our Indian Scout from earlier, certain powertrain fault codes can be retrieved and read, and possibly even some live sensor data. But full repair access is difficult to come by. In the case of Polaris, bi-directional command of a motorcycle is limited to… well, to nothing. Bi-directional controls allow a mechanic to command a module on the motorcycle to perform specific tests and functions. It's also needed for coding — recalibrating and reinitializing electronic items like a new throttle body unit, for example. Those controls also allow reprogramming different parameters into the motorcycle. Those parameters could be something potentially environmentally harmful, like altering fuel maps, or something a bit more innocuous, like changing a service interval or adjusting idle speed.

Now, of course, you could get that control by coughing up for Polaris' diagnostic unit, the Digital Wrench. And then, obviously, you'd have to pay their monthly fee to use that scanner by getting access to the dealer portal. Add to that the cost of a factory service manual to cover diagnosis and procedures, and it becomes pretty easy to see why a small shop might just turn that work away, especially if they were not make-specific, and why a dealer, who is sort of semi-independent of the manufacturer, would charge beaucoup bucks to help recoup those costs, since they don't really have the luxury of not payin' 'em.

And you know who pays for that.

Now things aren't usually that bad. Not yet. Polaris, for example, actually offers dealer training, for free, on some procedures that an indie can access, which is actually really cool and I appreciate that greatly. But all sorts of things are going the way of locked-down information, even in the world of consumer goods. The winds of change seem to be blowing that direction in the automotive sector, and as you older riders have seen, the motorcycle industry often follows the four-wheel stuff.

Even adhering to tradition contributes to complexity

I’ve picked on Polaris here, but this sharp uptick in intricacy is in no way exclusive to them. Take, for instance, the new VVT 121 engine Harley-Davidson announced this summer. Now 115 horsies and 139 torques is nothing to sniff at, but a cam phaser on a Big Twin seems to be a parachronism. At this point, the layout — the basic idea of the motor's configuration — seems to be a rather glaring compromise. The narrow-angle V-twin is a study in design shortcomings, and I say this as a huge fan. Many years ago, the layout was chosen and retained for highly pragmatic reasons mostly involving cost and simplicity. I personally have dealt with the foibles because I like the noise and I think they're pretty easy to keep on the road.

But lately? Boy, there's a lot of stuff going on behind the scenes to stick with this air-cooled narrow-angle vee thing. The Milwaukee-Eight was heralded as a glorious return to the single-cam design when it debuted, but a cam phaser? I like Big Twins, like… a lot, but man, I don't want to work on that. Like, I will, if it pays, but at what point does the manufacturer step back and say, "Look, with emissions and noise requirements being what they are, maybe it's time we rethink what we're doing here." Porsche did it. Now their cars' engines are liquid-cooled. Ducati did it. Now their vee engines are fours. People seem to be buying those still.

If you've been a regular here for a long time, you may think of me as the "old junk" guy. That's fair, since I both initiated the Retrospective Review series and probably contribute to it more than any other author. And you may think that this talk about complexity is just my bias. But I also am a mechanic with a deeper need for income than validation of my own mechanical ideas. I work on everything. Motorcycle, car, truck, tractor, old, new… whatever. I don’t care what it is. I fix 'em all. So you could also say that the more complex something is, the more I can charge to repair it, so in theory this ever-increasing tech should work in my favor.

I don’t want to conclude this article with an opinion on complexity, because I'm not sure I have one. Some folks will consider the additional costs associated with complexity on a new motorcycle they buy today to be a fair trade for the greater performance they help yield. Those shopping those same machines in the used market in a few years may feel differently. And I understand why some in the "I'll do it myself, thanks" crowd are finding most machines have become too difficult to work on for them to even attempt it.

I know we’re all prone to thinking "the good old days" have passed on by. Heck, the "golden age of motorcycling" is pretty much a moving target. I feel like right now, we're still in a good spot. We can still go get some simple machines from yesteryear at modest prices, if we like. Yet if performance is the object of the heart, it exists with a slight mechanical service penalty in the form of money or time.

Perhaps the Golden Era of Motorcycling is going on right now.