By the middle of 1973 I was fed up with dragging my parts-bin Yamaha TD2B road racer around the race tracks of Northern California.

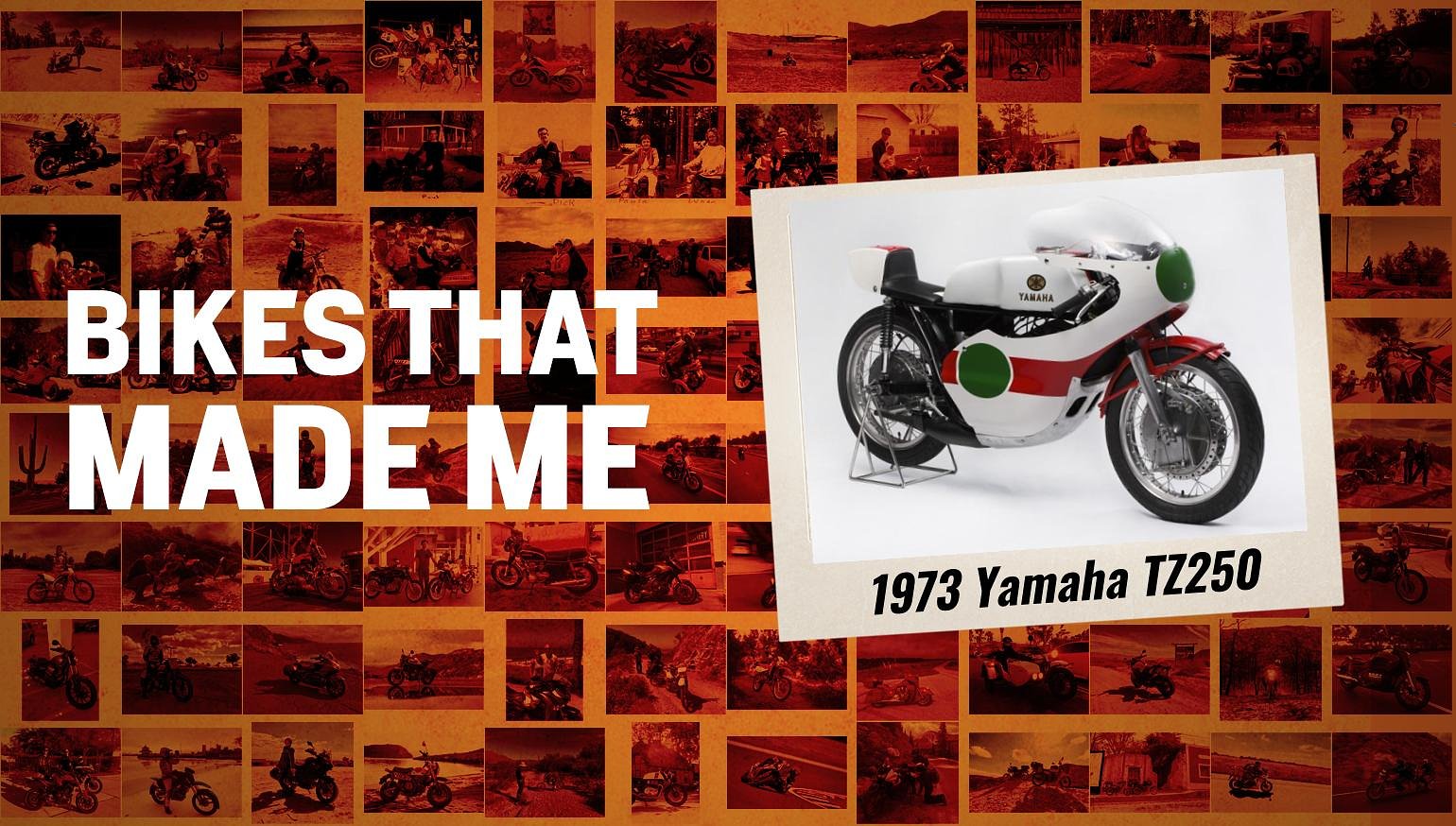

I had traded a dirt bike for the TD to a guy who worked at a Yamaha shop. He built the bike using the lunchbox method, which involved buying the large parts like the frame and swingarm and then ordering many of the smaller, less expensive parts through the parts department and smuggling them home in his lunchbox. When I took possession, the bike was a rolling chassis and boxes of engine and suspension parts, including a Ceriani fork of unknown origin and a fairing big enough to streamline a locomotive. I cobbled together a serviceable race bike and rode it in club races and one AMA National at Laguna Seca on my fresh pro license. A DNF there was the last straw. The next day I got on the waiting list for a brand new Yamaha TZ250A, the company’s first 250 cc water-cooled production road racer.

The TZ was a weapon, and a far better bike than I was a rider. It wasn't good enough to paper over the holes in my racing skills, but it was a valuable tool to help achieve progress toward that goal. I raced it throughout 1974 with measurably more success. One day a friend suggested I send in an entry for Daytona Speed Week in March.

“You have the bike, you have the license,“ he said. “All you need to do is get there. I’ll be your mechanic.”

It’s hard to convey just how dumb I was in those days. I had never been out of California in my life, and only occasionally out of the San Francisco Bay Area, where I grew up. I was an ambitionless 24-year-old kid working at a motorcycle accessories distributor in San Rafael, California, thinking I’d probably still be working there 30 years later and being pretty much OK with that.

At first I shot down my friend’s idea, ostensibly because it was a long way to go to be humiliated by guys who raced for a living. In reality, I was scared. Florida was the dark side of the moon to me, a universe away from my support system — my job, my friends, my family. What if something happened on the way? What if I crashed and got hurt? Where exactly was Florida, anyway? East? Where’s that, over there?

Travel is supposed to be broadening, but for me it was mind-blowing. Once we left California I watched nervously for dragons, cameleopards, and savages with their faces in their chests as depicted on medieval maps of unexplored parts of the world. It took two and a half days to drive from California to Daytona, and what felt like two weeks just to cross Texas, where I walked half-awake into a convenience store one night during a gas stop and heard a gravelly voice behind me mutter, “I’m gonna cut me a hippie tonight.” My hair was short by San Francisco standards but absolutely Rapunzel-esque to the denizens of that flyspeck burg. I didn’t get out of the van again until Louisiana.

My first morning in Florida was bitterly cold, which in my innocence I thought scandalous, even though it was early March.

“Where’s the sunshine and all the orange trees?” I grumbled to the man in line in front of me at the sign-up booth outside the Speedway. The man turned slowly to see who could possibly be that clueless and still operate a motorcycle. He was Gene Romero, who on the last day of Speed Week would win the 200-miler. After I signed up and skulked back to the van, convinced all eyes were on me, it hit me that I was going to be in the company of such giants — Roberts, Nixon, Agostini — all week, if by “in the company of” you meant sitting in the next stall in the infield rest room.

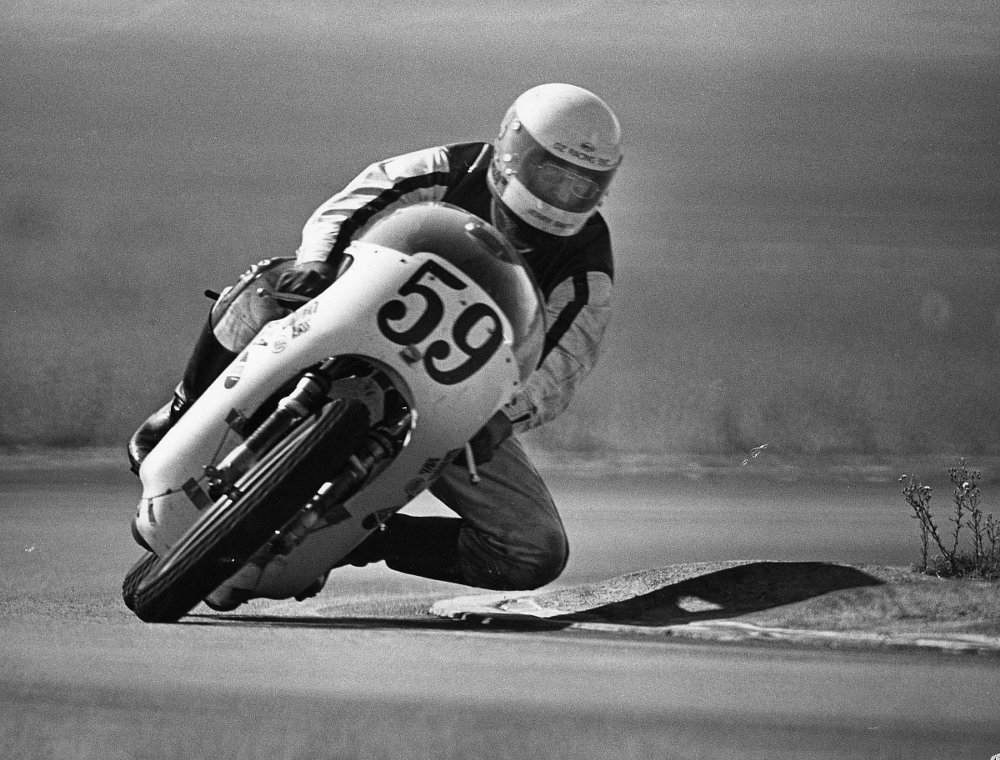

Racing was the one time in my sheltered life that I was allowed to do something stupid and dangerous without being warned how stupid and dangerous it was. For a timid soul such as myself — an outsider’s outsider in high school, a proto-nerd who was a Trekkie before there was a word for it — it was wildly freeing to get out on a race track, roll the throttle on and throw the bike into a fast corner. But the first time I heeled through the last left-hander in the Daytona infield and rode up the 31-degree banking aboard a crude little two-stroke on treaded Dunlop bias-ply tires, just a seized piston or a pinched inner tube away from hitting the deck at 140 and sliding — if I was lucky, tumbling if I wasn’t — toward a near-certain ambulance ride to the ER in Halifax Hospital… well, that’s when shit, as it sometimes does, got real.

Racing stopped being a game that day and became a heart-attack-serious sport. Unlike some of the pinkie-out gentleman racers I had competed against in the AFM, these guys were pros, as cuddly and welcoming to a rookie like me as a basket of rattlesnakes. I qualified midfield and started the Novice main on the last row of the first wave, holding the clutch in and gulping blue two-stroke smoke waiting for the green flag to drop. Seventy-six miles later, when they threw the checkered, I had finished about where I’d started. I hadn’t fallen off, or gotten in anyone’s way, and I didn’t die, not even once.

I raced for a few more years, as often as my laughably low salary permitted. I did all the work on the bike myself, taking my life into my own hands every time I torqued a bolt or changed main jets. I could probably still pull the crankshaft out of a TZ250A and have it sitting on the workbench in under an hour.

I rode Laguna Seca four or five times, Ontario Motor Speedway two or three, and Daytona again in ’76. That year I did poorly, and learned that failure isn’t permanent. You put your disappointment in a little box and throw that box away. Then you pack up your bike and your tools, go home, and come back next time better prepared. That’s a philosophy to embrace both on the track and off it.

It wasn’t until after I sold the TZ250 that I understood what it had done for me both as a racer and a person. It taught me to trust myself, not to be scared of the unknown, and how to be my own support system. It also taught me risk isn’t something to avoid. Some people die on race tracks, sure, but a lot more die sitting on the couch in front of the TV.

Go out into the world, do your best, take chances, and live the fullest life you can. It’s the only one you get.