The BMW K1200RS was already 21 years old, damn near an antique, but to me it still looked like the future.

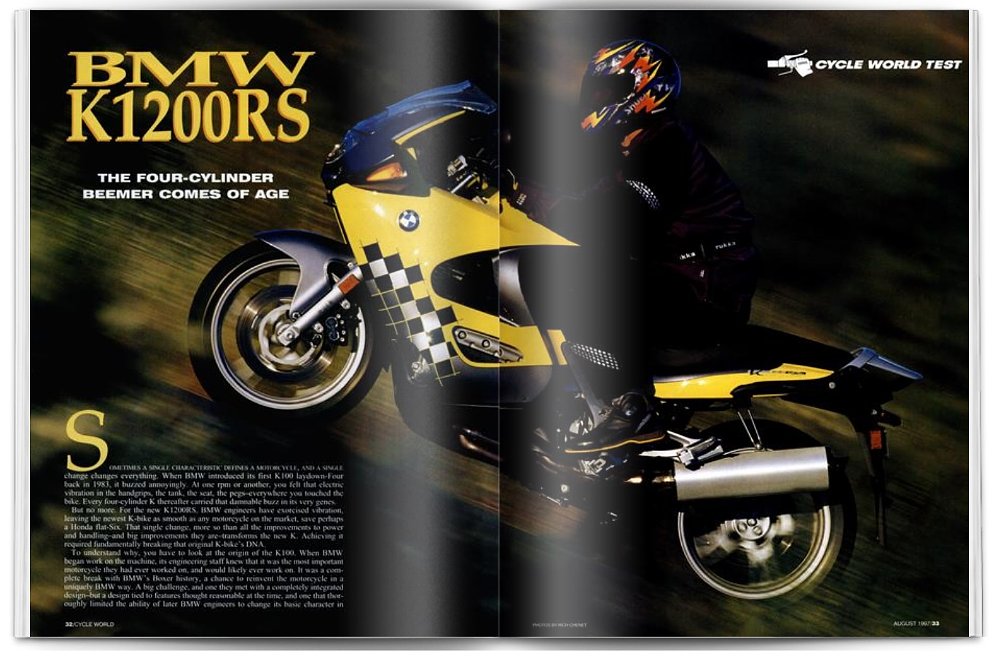

I paused in my task and just stood looking at this superb machine, yellow and gray crosshatch graphics enhancing a gaping maw that transitioned up and rearward into fairings that gave the impression they could completely escape the effects of fluid friction and atmospheric pressure. My eyes slipped across the curves and edges, moving back across the few strategically revealed mechanical bits and bobs toward the middle and end, the whole thing evoking visions of an F-86 Sabre in my nerdy mind.

It looked like it was testing the sound barrier even as it sat parked on its side stand. I had to force myself out of my reverie and get back to the job of trying to find where the DIN accessory outlet lived, so I could invite the motorcycle into the new millennium with a USB outlet.

A tiny plastic flap just below the seat caught my eye, and with an astigmatic squint I was able to make out the letters, "DIN 12V." Squatting down near the left foot peg, I pointed a finger, tapped the outlet, and said to no one in particular, "There you are!"

From the tree above, a cardinal chirped in what I could only assume was an affirmative manner, and then the motorcycle, no longer content to sit still and be an object of admiration, heaved off the stand and rolled over dramatically onto its right side with a sickening crash of splintering plastic. The cardinal flew off, chirping out what sounded remarkably like laughter. With that, on my second day of ownership, I relearned my first lesson as a returning rider — never entrust your parked bike to an incline, no matter how slight.

Leaving motorcycle orbit and then re-entry

The K was my first motorcycle in a decade's time, a purchase fueled by the massively multiplayer cabin fever doled out by the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. Its predecessor had been a 1978 Kawasaki KZ1000 LTD I parted with in the winter of 2010. The KZ had been my second motorcycle (the first was a much loved Suzuki SV650S) and an impulse purchase after taking a spirited ride on a meticulously restored 1973 Kawasaki Z1, an experience so pure and sensual that to this day it defines “motorcycling” in my mind.

Back in the 2000s, vintage UJMs littered the used market and could be found regularly in rideable condition for almost comically low prices. I picked up that KZ1000 for $1,200 and started learning about the joys (read: torment) of vintage motorcycling.

It leaked oil. Not profusely, but in that particularly irritating, inexorable way that left a persistent floor stain about the size of an Eisenhower dollar no matter how many seals or gaskets got replaced. The fueling was binary: either on or off. There was no "just cruise calmly" zone. After an overnight petcock valve failure followed by a massive gasoline cleanup effort (on a positive note, the gasoline pool dissolved the oil stain), I disassembled the carbs, wondered whether the gas had penetrated its way into the sump to infiltrate the oil, and decided I was far too lazy and impatient for this sort of thing and sold it to the first taker. Then came domestic life and the demands on time and budget that seem to spell the end of riding for so many.

Now, a decade later, apparently having learned nothing, I was staring at the underside of another now-vintage motorcycle — one that would be far more expensive and complicated to repair than a late-1970s UJM — wondering if I was making a horrible mistake. As with most horrible mistakes I make, I decided no, virtue was on my side and motorcycling is good and right.

With the help of my neighbor Fretless Joe (so nicknamed for his Pastorius-esque mastery of the fretless bass), we righted the K, I did some brief inspections, and ordered a new right rearview mirror assembly for a BMW-appropriate sum. Thus came relearned lesson two of the returning rider: Even cheap motorcycles are expensive when you're prone to stupidity. I also learned a totally new lesson in this instance — BMW side cases are robust and as good as frame sliders in the event of a tip-over; a lesson that would regrettably be reinforced a time or two more over the next few weeks as I began riding again after a decade-long layoff.

Luckily, none of the mistakes I would make during those few weeks would require further repair — they would just cause a crisis of confidence. I would have to relearn several fundamental things:

- Going fast is much easier than going slow (this is an illusion, of course).

- The clutch is more useful than the brake at low speed.

- Drivers in general — but specifically Subaru drivers — either passively or actively try to kill riders.

- Most importantly, I relearned that most basic motorcycling fact: Hubris will be your downfall, and the person least capable of recognizing hubris is yourself.

Just because I was an experienced rider before did not mean I was still an experienced rider. Skills are perishable.

Agonizing reappraisal

I absolutely loved that K1200RS. I remembered reading about it in Cycle World in 1998 and seeing the first photos of that artful yellow and gray crosshatch livery surrounding that massive gaping maw fairing around the radiator. When I saw this particular one on Craigslist for $3,000, it had to be mine.

Yes, I loved it, but I was ultimately terrified of it. I re-acclimated to speed surprisingly quickly, but riding the big BMW at parking lot pace felt like gladiatorial combat just to keep it right side up. Multiple low-speed drops, always on inclines, and my subsequent inability to right the bike without assistance, eventually chilled my enthusiasm to ride it, despite the sublime hours cruising and the sentimentality associated with owning a bike I thought in my younger days was just about the coolest thing I'd ever seen.

In hindsight, I came to regret overestimating the ease with which I'd recover my riding skills, and the BMW became an excellent delivery system for humility. In a triumph of wisdom uncharacteristic for me, I did two things. First, I signed up for an MSF course to shake off the 10-year-thick rust. Second, I downsized to a motorcycle so ridiculous as to be endearing: a Royal Enfield Himalayan. From one end of the spectrum to the other, you could say, because I figured if I'm going to begin again, I may as well walk all the way back to the beginning. And I can happily report the Himalayan has been a cheerful and enthusiastic companion on rides long and short. It has outperformed every single expectation I could've reasonably put on it.

Re-entered, stage two

The moto world changed dramatically in my 10-year absence. Adventure bikes rule the roost, "middleweight" stretches all the way up to 900 cc or more, and 100 horsepower seems to be the minimum to be taken seriously. Getting back up to speed has made me feel old, but twisting the throttle still makes me feel young.

There's no doubt my choice of the BMW was a poor one for a re-entry bike, despite how special it was to me. That said, now that I've had some time to get reacquainted with riding, I have discovered that occasionally I am a competent rider. I'm beginning to think it might be time to buy a second bike, one more capable of haste.

I almost wish I hadn’t sold it.