Fifty years ago this month, Dick Mann won the Daytona 200 on a factory-entered Honda CB750. The story of getting Honda's ground-breaking bike into the race and the events that happened in the pits involved more drama than the race itself.

Honda unveiled the 750-Four at the Tokyo Motor Show late in 1968. It was not widely available in the United States until after the 1969 Daytona 200 but was sure to figure in the 1970 show, along with new triples from Triumph and BSA and the new XR750TT from Harley-Davidson. Major bragging rights were on the line.

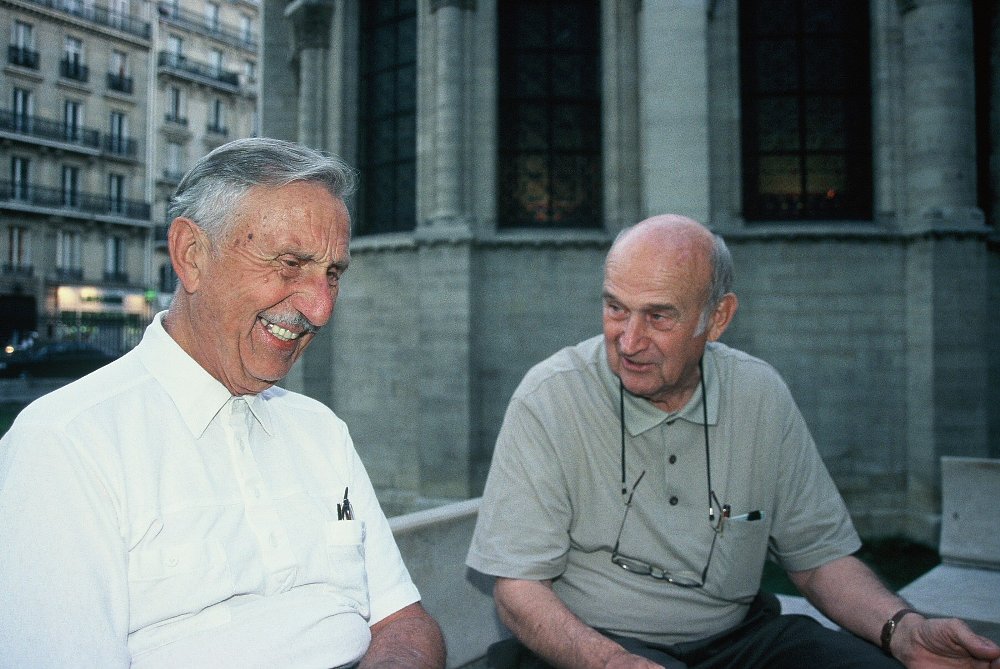

Bob Hansen was American Honda’s most senior and trusted U.S. employee. Back then, he was the only American with the ear of the Honda Board of Directors. He also ran a backdoor works racing team out of his home.

At a meeting of Honda bigwigs in 1969, Hansen suggested that Honda field a factory effort in the following spring’s Daytona 200. He was told that the 750-Four had not been designed as a racing platform (which was true, notwithstanding the availability of an extensive — and expensive — kit of race parts).

Had Honda intended their road-going four to function as a racing platform, the company would have used gear-driven, dual-overhead cams and four-valve heads, as they did on their GP bikes. The company was afraid that the 750 would not win. But Hansen told the board, “I’ve sold 1,200 of these things in my region alone. I know that some of those bikes will end up on the grid at Daytona, and they [those privateer bikes] will not win.”

Yoshiro Harada, Honda’s R&D representative, asked Hansen, “How fast would a bike have to go to win the race?” Hansen picked a figure of 150 mph out of thin air, and the meeting moved on to other topics.

“I forgot about it. When I didn’t hear from them, I figured that the factory had decided against Daytona,” Hansen told me. “Then I got a phone call from Harada. All he said was, ‘You’ll get four bikes.’”

Even back then, Honda R&D had simulation algorithms for every major racetrack. They ran the numbers. They knew exactly what horsepower, weight, and frontal area they needed to achieve to field a competitive bike.

Once committed to the Daytona project, Honda spared no expense or effort. They drafted several of their World Championship riders and mechanics, who were based in Britain. Hansen again raised his voice, insisting that at least one American get a seat — both out of patriotism and because he believed experience counted for a lot at Daytona International Speedway, where technique and strategy were so important. A U.S. rider would give a win even more marketing impact, too.

The question was, which American should get the seat?

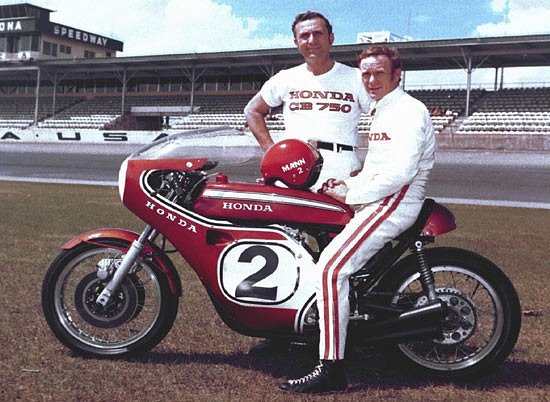

BSA had been very active on the U.S. racing scene throughout the 1960s. One of their stars was Dick Mann, who won the national championship in 1963, riding for BSA (he also rode a Matchless that season). BSA’s new Rocket 3 was a vastly more potent and sophisticated race platform than the Gold Star that Mann had used in AMA road races. Mann would doubtless have loved to get his hands on the triple, but BSA felt that Mann was too old, at 35, and did not renew his contract for 1970.

Hansen knew that Mann was unemployed and that he’d be the perfect token Yank. “I called him up,” Hansen recounted years afterward, “and said, ‘Hello, Richard, what are your plans for Daytona? How would you like to ride a Honda?’”

Hansen advised Mann to drive a hard bargain with Honda’s Japanese executives.

“I told him, what you’re going to ask for is $5,000 to put your leg over it, and a $10,000 bonus if you win.” Mann was afraid that such an exorbitant demand would price him out of the market. “Jesus, Hansen!” he replied. “I need the ride!”

CB750s arrive at Daytona

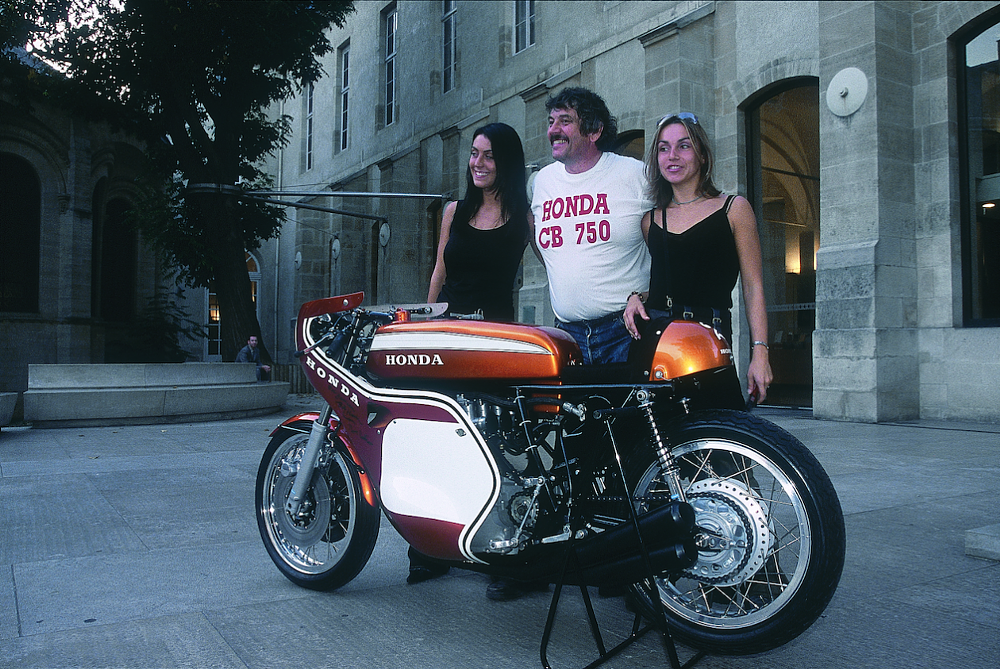

Four crated Honda 750-Fours arrived, along with a load of spare parts, just in time to be forwarded to Daytona. The bikes were not technically “CR750” models (that term is properly used to describe kitted road bikes) but rather were “CB750 Racing Types.” The bikes came through U.S. customs labeled “experimental.”

Honda’s multicultural team met up in the Daytona paddock. Hansen seconded Ron Robbins and Bob Jamieson, two American Honda technicians well versed in the new fours. From the U.K. came Tommy Robb and Ralph Bryans, who were both Grand Prix winners. The third British rider was Bill Smith, an experienced racer and Honda dealer. Steve Murray was the lead British mechanic, and he brought two assistants. The senior Honda executive on the scene was Yoshio Nakamura, who normally managed Honda’s Formula One racing in Europe. Honda wasn’t the only team bringing in heavies from the glamorous car scene; BSA enticed Mike Hailwood away from car racing, too.

When Hansen and his crew opened the crates, they couldn’t believe their eyes. Despite a short lead-time, Honda had delivered very trick bikes. They had magnesium cases and dripped with titanium parts. The four machines arrived with various cams and made from about 90 to nearly 100 horsepower.

In fact, they were so exotic as to be well outside the homologation rules in effect at the time. As Ron Robbins recalled archly, “I’m not saying they were cheater bikes, but the rules specified that frame had to be stock. Well, a stock bike’s frame was made of mild steel. I had to weld on the race bikes, and let’s just say, chrome-molybdenum smells totally different when you’re welding on it.” Nonetheless, the bikes cleared tech.

The four machines didn’t have an easy time of it in practice and qualifying. They didn’t drip with just titanium, they also dripped with plain old oil. Robb’s machine leaked right through its porous, sand-cast cases. He came in with his boots soaked.

“It’s like riding a bloody Norton,” he told his wrench. The exhausts were prone to cracking and needed regular welding up.

Worst of all, Bryans crashed early on, and his machine burned like a torch. When the British mechanics announced that they’d rebuild it, Hansen was horrified.

“They said they had enough parts,” he recalled, “but they didn’t have any spare frames.” Hansen feared that the frame had been exposed to too much heat. An argument ensued, and by the time it was over, the U.S. had declared its independence from Britain. Hansen, Robbins, and Jamieson would run Mann’s bike, while the three British mechanics looked after Robb, Bryans and Smith.

Qualifying and racing reveal the problems

Grid positions were based on single-bike time trials that took place on the oval only, not the road course. Hansen stood at the pit wall as Mann howled past on the Honda and thought he heard the clutch slipping.

Then Robbins and Jamieson drained the oil from the bike and found it polluted with tiny black balls of some rubbery material. That may have accounted for bad clutch hookup, but it also foreshadowed a more serious problem. Because the American mechanics had worked on Honda’s road bikes — not Grand Prix racers with gear-driven cams — they knew that the black plastic fragments meant the cam chain tensioner was disintegrating.

Jamieson walked over to the British mechanics with a bit of the polluted oil on his fingertips and explained the problem. Hansen, figuring that the less mileage he put on his race bike the better, told Mann to skip the rest of practice and head to the beach. Jamieson and Robbins tore into Mann’s motor, cleaned the rubber out of the oilways and replaced the tensioner. The British mechanics had no intention of following suit.

“They decided to go to the short-track races,” Jamieson recalled. “I was thunderstruck. I told Steve Murray and Tommy Robb, ‘These things could seize, you could get hurt. Other people could get hurt.’”

Jamieson knew that besides causing clutch slippage, the bits of tensioner clogged the oil pump. If the tensioner failed before oil-starvation, the bikes could chop their valve trains into very expensive swarf; if the oil pump failed... Either way, the prospects for a 200-mile race, of which 100-plus miles were wide open on the banking, were not good.

Based on the time trials, the first five machines were Gene Romero (Triumph Trident), Hailwood (BSA Rocket III), Gary Nixon (Triumph Trident), Mann, and Kel Carruthers on a Yamaha 350 cc two-stroke. After the warm-up on the morning of the race, Mann came back and told Hansen the bike was running better than ever. That was borne out when the race began: Mann and the Honda quickly opened up a big gap.

The Daytona 200 is a hard race to win on undeveloped machinery. One by one, most of the BSAs and all the factory Harley-Davidsons (early, iron-head models) dropped out. Hailwood only lasted 10 laps; Cal Rayborn, the fastest of the Harley men, lasted about 100 miles. Most of the Hondas failed to finish, too. Smith was a DNS. Ralph Bryans managed only three laps. Robb did 12.

During a fuel stop, Hansen instructed Mann to roll out of the throttle and conserve his machine.

In the late going, with his Grand Prix stars out of the running, Nakamura renewed his interest in Dick Mann. Romero, after a slow start, was gaining ground on his Triumph. Hansen watched from the pit wall with a stopwatch and signal board. Nakamura came out and told Hansen, “He [Mann] must speed up,” pointing out the fact that Romero was, at that point, lapping much more quickly.

There was yet another argument. Hansen refused a direct order from Nakamura. Finally, the American extended his arm and pointed, telling the Japanese executive, “Get back to the pit!”

This would have amounted to insubordination in an American company. But it was truly shocking in a Japanese context.

Hansen was sure Romero was too far back to catch Mann before the finish. Moreover, he was certain that Mann’s bike could not handle any additional stress. To his finely tuned ear, the machine already sounded off-song.

In the end, Mann and machine did — just barely — last long enough to get the win. It was Mann’s first victory in the 200 after about 15 tries and several second-place finishes, so it was a popular victory.

Ironically, Honda did not return to Daytona the following year; I guess they quit while they were ahead. BSA reconsidered its ageism, and rehired Mann for 1971. He won again on a Rocket 3.

Last but not least, among the ironies: Bob Hansen was sure that his insubordination with Nakamura had been a firing offense. Shortly after returning to his office in Torrance, California, he saw a new Honda organizational chart without his name on it, and he assumed the company was about to terminate him.

He was just that kind of stubborn, and would rather jump than be pushed, so he resigned. Hansen was immediately hired by Kawasaki and he lured Yvon Duhamel (who had finished just off the podium at Daytona) to Kawasaki. Hansen told me that he was also the one who chose the color now known around the world as “mean green.” He went on to play a huge role in establishing Kawasaki as a force on American racetracks and in the U.S. motorcycle market.

Years later, someone at Honda told him, “We didn’t have you on the organizational chart because we wanted to create a position for you in which you’d have total freedom to pursue any project!”