Modern motorcycles are complex — sometimes, overly so. That wasn’t always the status quo, though.

In its elemental form, a motorbike is an engine, a frame, and two wheels (sometimes, three). That still holds true today. The nucleus hasn’t changed all that much. It’s the systems surrounding it that have.

Today’s motorcycles are laden with advanced features. There’s radar-guided cruise control. There’s wheelie control, slide control, and launch control, you name it. Even sub-400 cc bikes come standard with multi-level traction control and full-color TFT displays. In many ways, it’s tech for tech’s sake.

Maybe that’s why Honda’s GB350, an air-cooled retro roadster, appeals to so many riders.

Grass is always greener…

If the GB350 looks at all familiar, that’s because it’s mechanically and aesthetically identical to the H’ness CB350. Honda manufactures the latter in India for the Indian market, but its Kumamoto facility produces the former for Japan and Australia. Sending either variant Stateside isn’t in Big Red’s big plans, despite the H’ness CB350 garnering positive feedback during its 2020 unveiling.

That’s why I jumped at the chance to hop aboard the classically styled runabout. With several weeks remaining in my extended stay in Japan, riding the GB was a no-brainer. Not only does it woo enthusiasts and passersby with nostalgic charm, it also suits Tokyo’s endless urban sprawl. The little city bike doesn’t do that with hordes of horsepower, flashy color schemes, or advanced features. It does so with simplicity.

Plain and simple

These days, air-cooled engines are few and far between. There’s one reason for that: modern emission standards. Unlike their liquid-cooled counterparts, air-cooled mills experience greater temperature fluctuations during operation. That, in turn, causes internal components to expand and contract, which warrants larger clearances. Those looser tolerances can lead to incomplete fuel combustion, and therefore, more emissions.

One way to minimize those disadvantages is by minimizing heat. After all, that’s one major byproduct of performance. The less performance demanded of a powerplant, the less heat it generates. That’s the route Honda takes with its 348 cc air-cooled single. Not only is the engine undersquare, with a 70 mm bore and a 90.5 mm stroke, but its 9.5:1 compression ratio also leans in the economical direction.

The result is 20 horsepower (at 5,500 rpm) and 21.4 foot-pounds of torque (at 3,000 rpm). Yes, it’s safe to assume the under-stressed engine won’t blow your eyelids back. But then again, the model’s superpower isn’t speed, it’s sensibility and simplicity. The chassis in which that engine lives follows those same tenets.

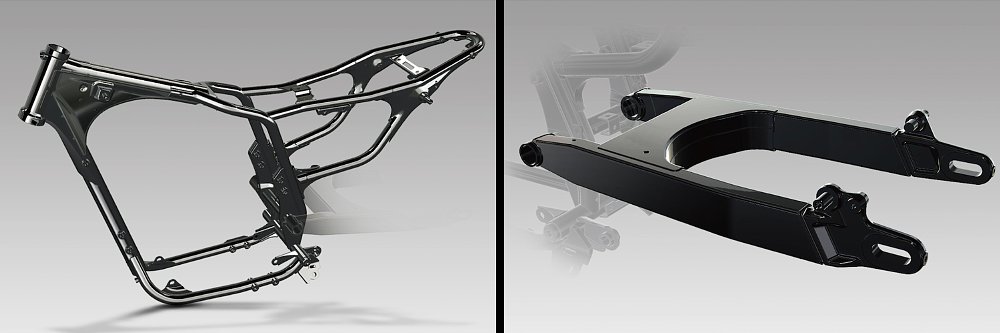

The twin-powered CB350s of the late 1960s and early ‘70s clearly influenced the GB350’s styling, but the similarities go under the surface, as well. The CB featured a cradle-style frame and a steel swingarm. So does the GB. The CB was flanked by a telescopic fork and dual rear shocks. So is the GB. Talk about a chip off the old iron block. That doesn’t mean the GB doesn’t buck conventions in other ways. Take the wheels, for instance, which are cast aluminum, not wire-spoked, allowing for tubeless tires. The disc brakes are just as practical, foregoing the drum setups of yore.

It’s irrefutable, the GB350 looks timeless, from its tins to its bench seat. What’s truly impressive is how Honda integrates technology into that throwback package. It sports a round headlight bucket and a fender-mounted taillight, but there’s LED lighting all around. An analog speedo lives in its single round gauge, but ABS (non-switchable) and Honda Selectable Torque Control (HSTC) icons flash on the instrument cluster. Those modern touches are only acceptable because they take a backseat to the GB’s main draw: its retro riding experience.

The short of it

The clock hasn’t even struck 8 a.m. yet and it’s already 85 degrees (F) in Tokyo. Partial cloud cover offers little relief when the humidity is 80%. It sure doesn’t help when you’re seated aboard the GB350, like I am, imploring a city traffic light to turn green. At idle, the engine doesn’t so much rumble as it hums. It doesn’t shake, it purrs. The heat radiating off its single-cylinder block is material, but it isn’t overwhelming. It’s present but not punishing. In such weather, placing any internal combustion engine between your legs only welcomes discomfort, especially at a standstill.

When the signal finally flashes green, I dump the clutch and pin the throttle. The GB pulls ahead; it doesn’t dart ahead. Its drive isn’t sluggish, but it isn’t snappy, either. Under acceleration, the long-stroke thumper chugs along, delivering the tactile sensations of an agricultural machine. Think somewhere between a tractor and a lawnmower. The sound issuing from its tailpipe is slightly visceral yet humorous. Think somewhere between a jackhammer and flatulence (that sounds painful, actually).

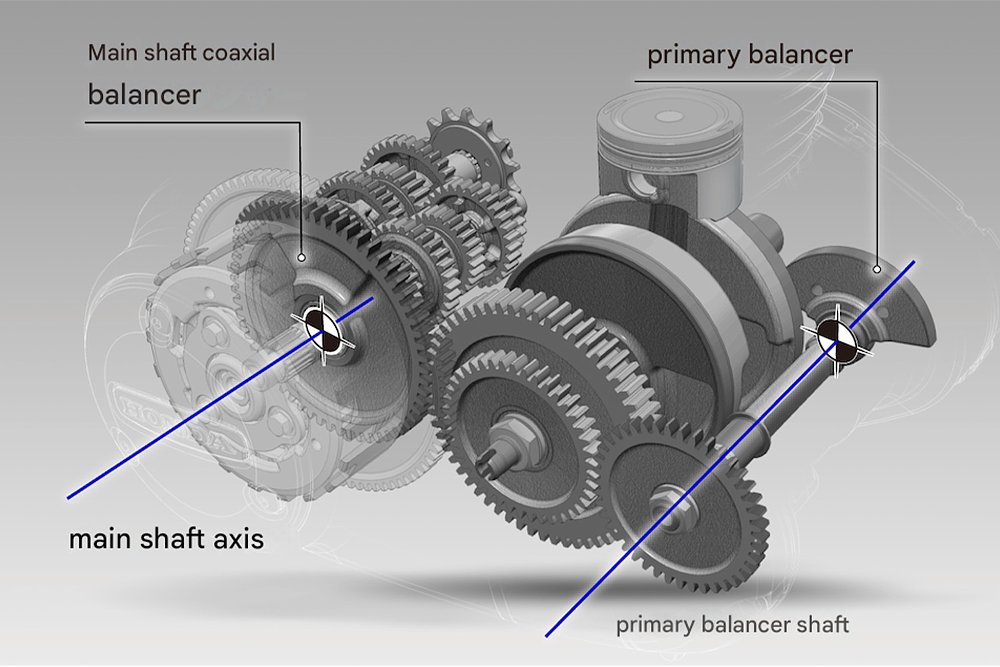

That’s not to say the ride experience is unrefined, though. To cancel out what it labels as “unpleasant” engine vibes, Honda enlists dual balancers, with a primary balancer operating in tandem with the crankshaft and a coaxial balancer installed on the transmission’s main shaft. The strategy is largely successful, too. Vibrations are always tangible — rising and falling in proportion to acceleration — but they’re never irksome. It's rarely buzzy through the bars or harsh through the footpegs. In that way, the GB finds a happy medium. It favors that approach in more ways than one.

Transferring the engine’s claimed 20 horses to the back wheel is a five-speed transmission. If given the choice, I almost always prefer a sixth gear, but I hardly missed it on the GB350. That’s because Honda spaced the gearbox for usability in all situations, not just for acceleration in the city. I often chose to blend into traffic rather than squeezing through it. I not only attribute that to the Honda’s even-keeled drive, but also its steering.

The GB350 falls into the sub-400 cc category. It isn’t as fleet of foot as many of its contemporaries, though. That’s not to call the model’s steering lazy, but that’s not to call it lively, either. Some of that comes down to its 19-inch front wheel. Its 27-degree rake and 4.7-inch trail likely play a role, too. While the GB’s handling informs its manners on surface streets, it's even more influential beyond the city’s confines.

The long of it

If you’re looking for curvy roads, Tokyo isn’t the place for you. The vast majority of its corners are low-speed, 90-degree intersection turns. Riding any semblance of twisties requires venturing outside the megalopolis. That search sent me east, to the Chiba Prefecture via Route 357. Thirty miles of expressway separate Tokyo’s bustling streets and Sakura’s lush farmland, providing the ideal grounds to test the GB350’s highway chops.

There’s one reason Honda’s five-speed transmission is well-suited to Japan’s expressways: appropriate gear ratios (for a small-bore single, anyway). While I often shifted to second at 30 kph (19 mph), I didn’t grab third until 70 kph (43 mph) and fourth until 90 kph (56 mph). If you notice, I left out fifth gear. Here’s why: I didn’t always use it. The GB reaches its top speed in fourth, so fifth is only necessary if engine vibrations become bothersome. Unfortunately, that top speed, no matter what gear you’re in, isn’t very inspiring.

At full throttle, the speedo needle struggles to surpass the 120 kph mark. Only once did I reach 122 kph (76 mph). The thing is, the speedometer doesn’t tell the full story. With Google Maps and REVER simultaneously tracking my ride, the GB only recorded a top speed of 115 kph (72 mph). That four-mph difference may seem negligible on Japanese roadways, but for someone who’s used to U.S. Interstate speeds, it’s considerable. The GB350’s easy-going nature isn’t limited to the expressway, either.

The winding roads around the town of Sakura are neither tight nor sweeping, neither technical nor fast. Aside from a few blind bends and low-gear dog-legs, the roads are ribbons of gently flowing corners. Fortunately for the GB, that matches its abilities. The bike seemingly floats through increasing-radius turns and loose S-curves, smoothly gliding from corner to corner. It’s a characteristic to be expected from a standard of the GB350’s ilk. Although, things change when the pace picks up.

The GB is built to mimic old bikes, and it does so, for better or worse. The brakes, for instance, are wooden, requiring the application of both front and rear brakes to make most corners. The poorly damped suspension is just as problematic. It doesn’t just wallow mid-corner but also blows through its stroke over most bumps. The pegs are quick to scrape and the engine is slow to rev. In that way, the GB350 dictates its own pace. Kick back and let the curves come to you, turbo. Despite the GB's performance limitations, I can still see why its such a sought-after machine.

The bottom line

Part of me wants to absolve Honda for not shipping the GB350 to the United States. I could argue that the model’s highway capabilities alone support that decision. At least, that’s the excuse I’m willing to grant Big Red. But it’s not that simple, now is it? Not in a market where Royal Enfield’s 350 series exists.

Royal Enfield basically corners the small-capacity air-cooled segment in the States with models like the Hunter 350 ($4,299), Meteor 350 ($4,899), and Classic 350 ($4,999). In Japan, the GB350 starts at ¥649,000. Given current exchange rates, a U.S.-bound GB350 could cost as low as $4,400. Presumably, current import duties would raise that MSRP, but if Honda could manage a comparable price, the GB would easily challenge RE’s category monopoly. Even so, the Japanese OEM hasn't revealed plans to send the model Stateside.

That’s an even sadder reality after spending a day with Honda’s stone-simple standard. Yes, modern motorcycles are complex, but the GB350 proves that they don’t have to be.

| 2024 Honda GB350 | |

|---|---|

| Price (MSRP) | ¥649,000 ($4,400) |

| Engine | 348 cc, air-cooled, two-valve, single |

|

Transmission, final drive |

Five-speed, chain |

| Claimed horsepower | 20 @ 5,500 rpm |

| Claimed torque | 21.4 foot-pounds @ 3,000 rpm |

| Frame | Steel semi-double cradle |

| Front suspension | 41 mm fork; 4.7 inches of travel |

| Rear suspension | Dual shocks, adjustable for spring preload; 4.7 inches of travel |

| Front brake | Nissin two-piston caliper; 310 mm disc with ABS |

| Rear brake | Single-piston caliper, 240 mm disc with ABS |

| Rake, trail | 27.0 degrees, 120mm (4.7 inches) |

| Wheelbase | 1,440 mm (56.7 inches) |

| Seat height | 800 mm (31.5 inches) |

| Fuel capacity | 15 liters (4.0 gallons) |

| Tires | Dunlop Arrowmax GT601, 100/90-19 front, 130/70-18 rear |

| Claimed weight | 179 kg (394.6 pounds) |

| Available | Now |

| Warranty | 24 months |

| More info | honda.co.jp |