Over the years, I’ve put a lot of miles on BMW F-series GS models, including the press introduction of the updated F 850 GS in 2018 and nearly 2,000 miles on a long-term loaner when I took one to the inaugural Get On! ADV Festival in South Dakota. And while I enjoyed my time with the F 850 GS, it always felt out of step with the rest of the mid-sized adventure class.

It was among the heaviest, had dinky little foot pegs that were uncomfortable to stand on, and a rear brake pedal and shifter that were difficult (at best) to use with off-road boots. The front suspension wasn’t adjustable, the rear shock was electronic, and the whole bike felt woefully soft. Plus it cost more than most of its competition. While it wasn’t a bad motorcycle, it stagnated in an increasingly popular class.

Meanwhile, when BMW recently revealed the new R 1300 GS, it took a stark departure from tradition and reduced weight and size to make the bike more capable for dual-purpose use. The “Adventure” variant still exists for those who want a long-distance, touring-focused machine. Now, BMW has given the same treatment to the F 900 GS. As I went to Las Vegas for a first test ride, I was silently hoping the changes were more than just skin deep.

The BMW F 900 GS

If you knew nothing else about the new F 900 GS aside from seeing one in a photo, you would know that something had changed in the F-bike’s demeanor. Gone are the extra plastic panels surrounding the tank and overly pronounced front beak. Gone is the chubby tail section of the F 850 GS with the sleek subframe now exposed and the tail section redesigned. The new bike also gets a lighter Akrapovič exhaust, and narrower, flatter rally-esque seat. And while I rarely comment on looks, as they’re subjective, I’ve decided to break my own rules and kick this review off by saying that the F 900 GS looks damn good.

Muscular… Aggressive… Dangerous. Almost like it’s poised for battle. And fresh in a way that stands out from the current crop of ADV bikes. The styling caught my attention from the get-go and had me volunteering for this assignment out of a genuine curiosity to see if the new bike delivers on this new makeover.

Taking a front-to-back approach in attacking the details on the new F 900 GS, the new windshield conjures up visions of a rally tower with a beveled edge designed to disturb the air rather than outright block it. Below sits a redesigned headlight offering the F 900 GS a much needed facelift while claiming a 1.3-pound reduction in weight and improved low-beam visibility for the rider.

One of the most highly debated critiques of the new design was BMW’s decision to redesign the new plastic fuel tank (nearly 10 pounds lighter than the previous steel tank) and reduce the bike’s overall fuel capacity to 3.8 gallons (down from 4 gallons). However, if BMW’s claims of 53 miles per gallon turn out to be accurate, the average adventure rider would still find themselves with a range of over 200 miles per tank. Spoiler alert: The best I was able to manage was 43.7 mpg, but more on that later.

Sipping up all that fuel was the newly redesigned 895 cc, 270-degree, parallel-twin engine. Up from 853 ccs, the new engine gets an increase of two millimeters in cylinder bore to 86 mm and retains its 77 mm of stroke. The engine also gets updated cylinder heads and new forged pistons versus the previous engine’s cast pistons. The engine is still being produced via a partnership with Loncin Holdings, in China, a move that alienated some die-hard BMW fans when it was announced for the F 850 GS back in 2018. Final assembly, however, takes place in Berlin, Germany.

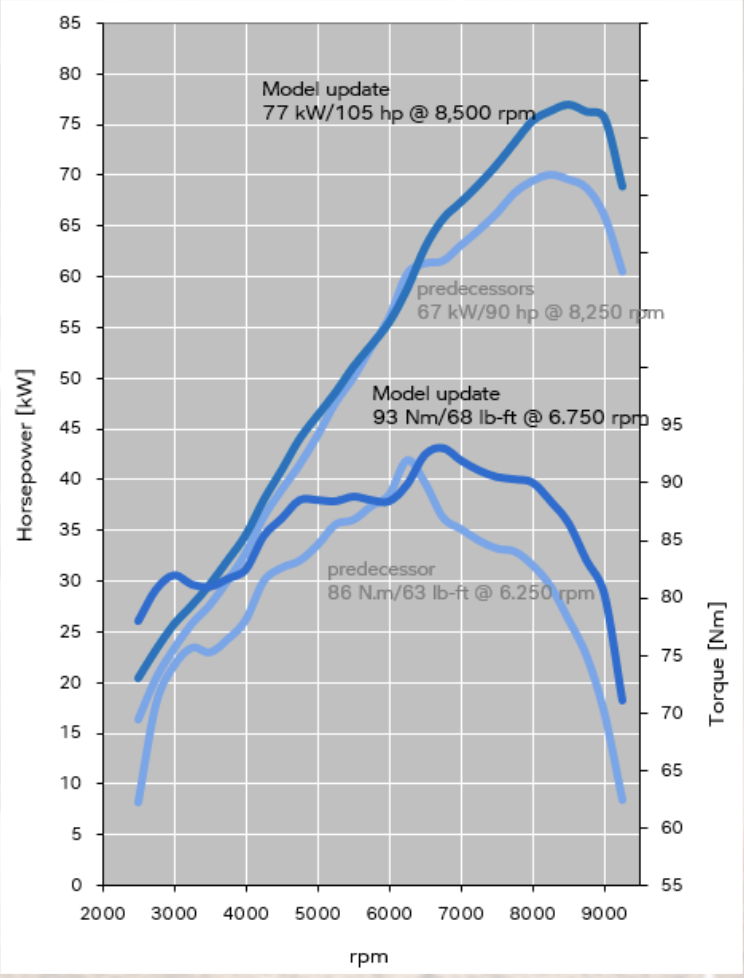

If the engine’s claimed 105 horsepower and 69 foot-pounds of torque are to be believed, the new F 900 GS powerplant sits alongside the similarly powerful Ducati DesertX, Tiger 900 Rally Pro, and KTM 890 Adventure R models. Looking at the provided dyno charts from BMW comparing the F 900 GS against the outgoing engine, you can see the new engine makes much more torque in the lower end of the rev range with peak torque coming on slightly later and carrying through much further in the rev range. Combine that with a 17% bump in peak horsepower and this engine feels much more lively and balanced throughout the entire rev range.

Power is delivered through a six-speed gearbox and all of the bikes we rode were equipped with BMW’s optional Gear Shift Assist Pro (fancy Bavarian speak for “quickshifter”) that works the gearbox in both directions. Unlike the F 850 GS’s shifter, which had to be removed from the shift-shaft spline to move it up or down, the new shift lever is now easily adjusted via a pinch bolt to accommodate larger off-road boots. The new bike also sports larger, more appropriately supportive footpegs with nearly double the surface area of the previous pegs and they sit 20 mm (0.8 inches) lower than before.

The rear brake pedal has been adjusted to sit five millimeters (0.2 inches) higher than before and also includes the folding adjustment pedal as standard (this used to be an accessory part for the non-adventure model). The adjustable pedal lets the rider quickly add 20 mm (0.8 inches) of height. This is a welcome change from the previous F 850 GS, where I found myself bending the rear brake pedal up and duct taping one of the rubber inserts from the footpeg to the pedal to be able to control the rear brake.

The brakes are the same twin-piston Brembo calipers up front with a single-piston caliper at the rear wheel. ABS Pro provides lean-angle-sensitive braking control and is reduced at the rear wheel in Enduro mode and can be deactivated at the rear wheel in Enduro Pro mode. Dynamic Brake Control (DBC) is included in the optional “Pro” riding modes and deactivates the throttle once a certain amount of braking pressure is detected. One is led to believe this is to prevent unintentional “whiskey throttle” if the rider is getting in over their head. While the rider can manually turn off traction control with the push of a button on the dash, it doesn’t appear that there is any way to fully deactivate the ABS.

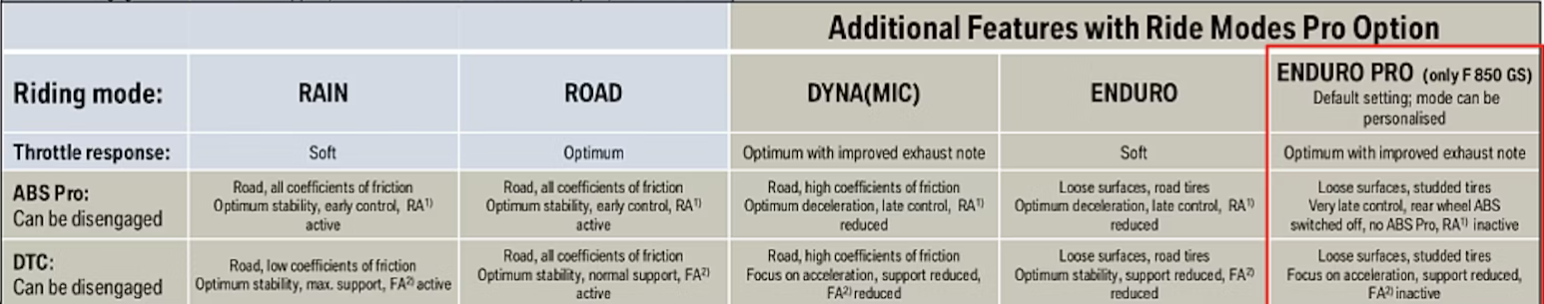

Ride Modes are controlled by a 6.5-inch TFT dash, which is now standard (this was a premium offering on the F 850 GS) across the F 900 GS line. Controls and ride modes are largely unchanged over the previous version, but much like the F 850 GS, the ride modes you get access to depend on the package you opt for. A fully outfitted F 900 GS will offer riders five ride modes: Rain, Road, Dynamic, Enduro, and Enduro Pro. Enduro Pro is the only ride mode that allows you to adjust the parameters for throttle response, ABS, and traction control.

Engine Drag Torque control is added to Ride Modes Pro, but can’t be adjusted. This essentially alters engine braking depending on the ride setting that is engaged. I couldn’t find much about this in the press material, but in the bike’s owner’s manual it says that in Rain and Road mode it is set for “maximum stability,” i.e. the tightest limit on engine braking, whereas Dynamic mode allows for less infusion of “stability,” and Enduro and Enduro Pro modes allow for “maximum performance” and “impaired stability,” meaning you can get the rear wheel sliding around.

Unlike the previous launch, BMW didn’t provide us with a breakdown chart of how each ride mode affects the bike’s performance, but I was able to dig up the chart from the F 850 launch and the modes, along with how they function, remain relatively unchanged.

Aside from the engine, the biggest change with the F 900 GS is the suspension. The F 900 GS gets two, all-new, manually adjustable, suspension options. Both upside-down front fork choices are made by Showa, feature 230 mm (9.1 inches) of travel, and are adjustable for pre-load, compression, and rebound damping. BMW claims that the upgraded version offers more rigidity, slider tubes that are two millimeters thicker, titanium nitride-coated (less susceptible to nicks from rocks and debris), and are half a pound lighter.

The rear shock options both provide 215 mm (8.5 inches) of travel. Whereas the base version allows for hydraulically adjustable preload, it only has a single rebound control. The upgraded ZF Sachs shock has hydraulically adjustable preload that’s easier to access, along with high- and low-speed compression and rebound damping adjustments. BMW claims the upgraded shock has a 25% wider adjustment range and 20% increase in absorption force. At the launch, I had the opportunity to ride them back to back to see if the increase in price was worth the investment.

Riding the BMW F 900 GS

The sun was already igniting the day when we pulled out of the hotel parking lot in Las Vegas and it felt good to be moving. Despite my brief introduction to my São Paulo Yellow F 900 GS prior to riding away, the controls were similar enough to those of the F 850 GS for me to feel fairly confident in piloting the mid-sized twin through the streets as we tried to keep up with our ride leader, Dennis.

Immediately, the engine was notably different from its predecessor. The handlebar pulled at my arms with a sense of urgency that the old motor seemed to lack. The chassis felt tight and competent, and despite my bike being outfitted with the lesser of the two suspension offerings, I was impressed with the overall damping and sportiness of the fork and shock as we zipped through town and up the on-ramp to Route 95 out of town.

Our little group settled into a rhythm, traveling about 80 mph northwest on the desert freeway. The engine felt calm, spinning just over 5,000 rpm in sixth gear and could wind up to 90 mph without breaking 6,000 rpm. The wind protection from the front shield was right up my alley. It spun the air in a way that kept the pressure off of my chest without any crazy buffeting around my head. I felt like I was riding through the wind versus fighting against it. Those of you out there who prefer a more “isolated” riding experience behind a larger shield will probably be turning to an aftermarket solution.

Pulling off of the highway and onto a two-track Jeep trail, we got our first taste of dust and dirt. The GS felt predictable and balanced, if not a little wide between my legs when standing. While the new pegs are an upgrade over the previous version, I would have preferred a bit more bite. Apparently BMW rounded off the edges to preserve riders’ boots at the expense of grip.

Our group spread out to stay out of one another’s dust clouds and looking down at my speedo I was rolling along at a brisk 40 mph, given the larger baby-head rocks strewn about. While the suspension felt planted and confidence-inspiring on the street, the jarring deflections of some of the bigger rocks were overloading the built-in steering damper. Reaching down, I was able to dial back two clicks of compression and one click of rebound damping without bothering to pull over. Just this small adjustment made a noticeable difference in smoothing out the bike’s performance in this unbalanced terrain.

30 miles, two photo stops, and one snack break later, our team of five riders regrouped at the end of the first dirt section of the day. While praise for the new bikes was solid, there was a clear chink in the F 900 GS’s armor: the tubeless, cross-spoked wheels. Four of the five bikes had bent rims and two of the front tires were completely flat. While the BMW wheel design means you don't have to run inner tubes and therefore allows you to plug a flat tire if you pick up a nail, it leaves the rider completely susceptible to air leaking out of a bent rim, a regular occurrence in the off-road space.

Neither the ride leaders nor the BMW support truck were carrying spare tubes or a hammer, so they resorted to beating the two rims with flat tires back into shape with rocks. Something to remember if you like to keep your bikes looking like pristine garage queens.

After scarring the rims with chunks of granite and airing the tires back up, we were on our way again. We turned left off of Route 95 onto Lee Canyon Road, which stretches perfectly straight across the desert before starting to coil itself up along the base of Mount Charleston. From there, we headed south on Deer Creek Road, which is nothing but fast sweeping curves up and down the foothills around the base of the mountains.

There is a great lookout point on this road that I’ve stopped at before that allows travelers to look northwest across the desert towards Frenchman Flats. If you would have done so on the right day back in 1951, you would have seen the first of a series of nuclear bomb tests that took place inside a 1,350-square-mile stretch of this desert, an area which became the principal nuclear weapons testing laboratory during the Cold War. History is wild.

On our ride, the desert was quiet and abnormally green from the winter’s snow and rain. The only sound was that of the F 900 GS’s muffled song as I ran it through the gears chasing the rest of my group of riders through the curves. The new bike handled the sweeping corners better than not only its predecessor, but also some of its peers. I was really impressed with how light and predictable the handling felt. The motorcycle naturally fell into a corner in a way that instilled confidence and urged me to go a little faster.

Throttle response was notably spot on. I was in Road Mode and the power felt crisp and strong, little to no flat spots or stumbles from the fueling. The engine pulled evenly off of idle and climbed damn near linearly straight up to redline just north of 9,000 rpm. It felt so much smoother than my personal KTM 890 Adventure R in the lower rev-range and the power felt more even and predictable throughout. Kind of like if a Yamaha Ténéré 700 engine made metallurgy love to a KTM 890 Adventure R. It was great.

As we stopped for lunch, a few of the bikes in our group, as well as some from the other groups, were rolling in on flat tires. This time, the mechanics borrowed a hammer from the staff at The Retreat on Charleston Peak and did their best to force the front wheels back into submission. While my rim had suffered a goose egg of a bend, it seemed to be holding air better than some. According to my bike’s Tire Pressure Monitoring system, I was only down about four to five pounds of pressure from the start of the day.

On the road again, Dennis was clearly hell bent on making up some of the time we lost over lunch and led us on a spirited ride along the outskirts of Vegas before heading west on Route 159 into Red Rock Canyon. It was here that the GS reminded me that I can’t use the electronic cruise control if the bike is in Enduro Pro mode. So I quickly cycled over to Dynamic mode, shut the throttle briefly to allow the system to shift between ride modes on the fly, and then set my cruise control speed. (Note: Dynamic mode was downright spicy. I found I preferred Road mode on the street).

Leaving the highway and heading north on Lovell Canyon Road, the broken asphalt soon turned to a rocky Jeep trail known as Lovell Summit Road with deep ruts in the dirt from the spring melt running down the hills. Switchbacks turned around on themselves as the trail climbed high above the desert floor. I soon recognized the route we were on as I had ridden it a few years earlier, only in reverse, during the tail end of the LAB2V Dual Sport ride.

It was here that I began to find the limitations of the base suspension. Setting up the front end with a little less compression and rebound damping helped with deflection over some of the bigger rocks at speed, but if I hit a water bar with a bit too much bravado, it was easy to bottom out the suspension in a hurry, at least at my weight of 220 pounds sans gear. So I cranked the damping back up and did my best to avoid the bigger rocks.

I know Zack and I have disagreed on this in the past, but I’m not a fan of quickshifters on ADV bikes. Don’t get me wrong, it’s fun jamming the bike through the gears on the open road, and this Bavarian quickshifter is smoother and works better than the one on my personal 890, but in tighter, slower, off-road terrain, they make the bike harder to shift when using the clutch and lead to a vague shift feel. On the F 900 GS, I found myself struggling with mis-shifts in those latter scenarios. On other models in this class, it’s not a problem because they allow you to turn off the quickshifter. I could find no such control on the F 900 GS’s dash nor in its manual. It seems like that would have been an easy electronic addition to offer up for the rider.

Our route spilled out onto Trout Canyon Road, a wide-open, seven-mile stretch of gravel and dust. I tried to ride just beyond the dust cloud of the next rider in front of me in an effort to keep both myself and the GS from sucking mouthfuls of silt into our lungs. It bears mention that I found that my favorite setting for riding off-road was a customized set up in Enduro Pro mode with the least aggressive throttle setting, ABS disabled at the rear wheel, and DTC completely disabled.

Regrouping at the intersection of Pahrump Valley Highway, we learned that our fearless ride leader Dennis had suffered his second flat tire of the day.

While Dennis assessed the situation, I used the opportunity to investigate the location of the F 900 GS’s air filter. While I was originally disappointed to find that it doesn’t live under the seat, as I was hoping for, I found it at the front of the gas tank in a spot under the fuel shroud that is relatively easy to access and clean. Good thing, too, considering it’s sitting right out in front of the bike.

Dennis got himself sorted and the rest of the ride back to Vegas was fast-paced if not uneventful. I rolled into the parking lot with about 19 psi in the front tire. The next day I snagged a Trophy colorway of the F 900 GS to ride back to Los Angeles to personally deliver to Mr. Courts for an episode of Daily Rider. I opted for the color change not just to secure a bike with a tire that was holding air, but also because it came with the Enduro Package, which includes the upgraded suspension along with a few other niceties.

I spent my second day riding solo, and enjoying the long way back to L.A., splitting my time on desert dirt roads running parallel to Interstate 15 and the highway itself. I had a blast testing the limits of the more expensive suspension (it felt more plush, and harder to bottom out), as well as getting used to the fact that this package also included bar risers. (I don’t normally appreciate bar risers, as they’re designed more for comfort, but BMW did a great job balancing comfort and performance with the ergonomics of this set up.)

Perhaps my right hand is a bit heavier than the average BMW factory test pilot, or perhaps I was just having too much fun, because I averaged 42 mpg during my ride back. The fuel warning light on the bike kicked on the first time with 113 miles on the trip meter and 117 miles the second time, after which I decided to push my luck and was officially out of fuel (according to the computer) by 139 miles. By the time I stopped for gas, my trip meter read 152 miles and the bike had used 3.5 gallons of its 3.8-gallon payload.

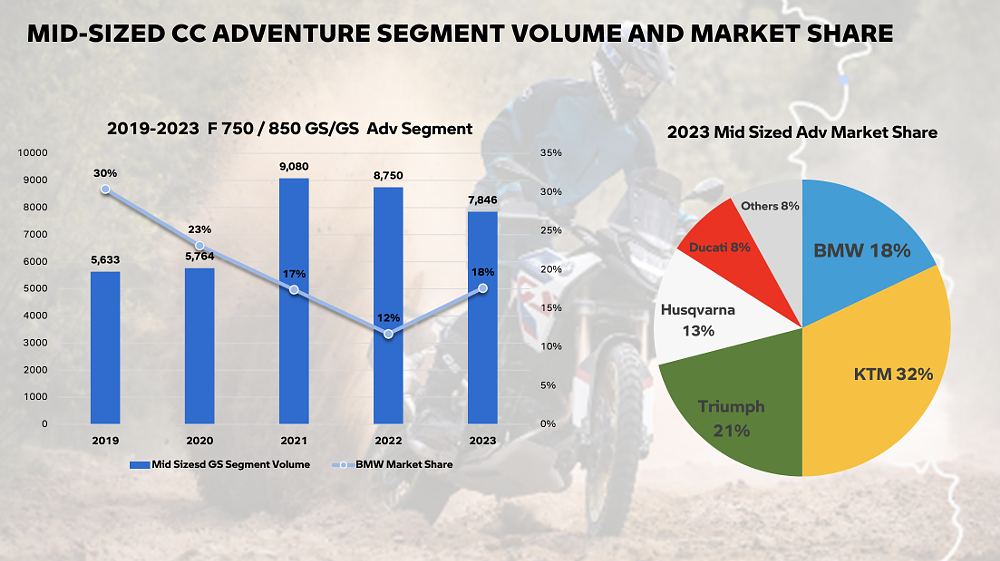

Not great. To my knowledge the F 900 GS has the most limited fuel capacity in the middleweight class. BMW still has the Adventure version with its larger tank for riders looking to traverse longer distances without stopping. With the F 900 GS, their goal is to give riders something lighter (our fully loaded test bike tipped our scales at 491 pounds with a full tank of gas, nine pounds heavier than BMW’s claimed weight for the base version), something sportier on the street, as well as something more nimble off road. They made no bones about the fact that they are aiming their sights squarely at KTM’s market share within this middleweight segment.

Pricing and the competition

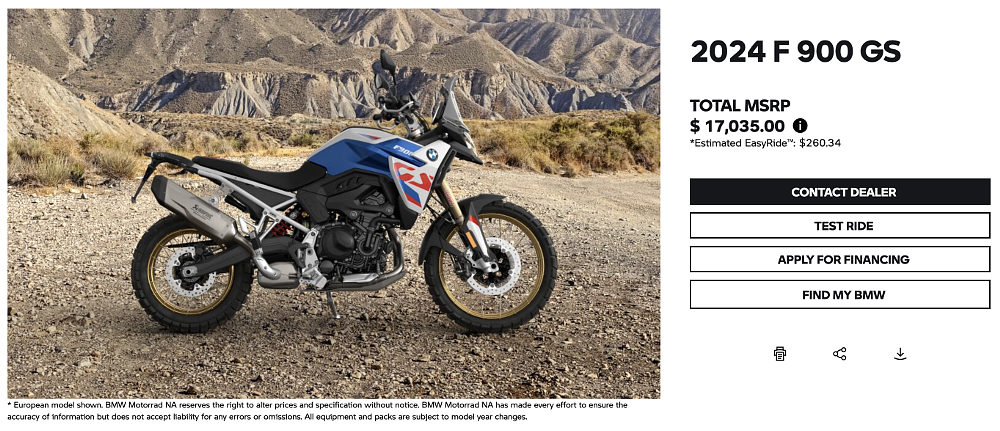

I’m not going to get into the whining about BMW’s pricing model — I’ll leave that for the comments section — but they sure as heck don’t make it easy. I spent more time getting the pricing right than I spent on any other portion of the review, and I'm still not 100% sure I've nailed it. Here’s what you need to know short of just heading over to BMW’s website for their "Build Your Own" bike feature (or better yet, call your dealer). The base MSRP of the F 900 GS in Black Storm Metallic is $13,495 plus a $695 destination fee. You’ll pay a $275 premium for São Paulo Yellow and $545 for the Red/White/Blue Trophy edition with gold rims (which as we learned are just as flimsy as the black ones).

From there it’s:

- $1,750 for the Premium Package (Gear Shift Assist Pro, Ride Modes Pro, M Endurance Chain, Keyless Ride, GPS Prep, TPM, Cruise Control)

- $2,500 for the Off-Road Package (Includes GS Trophy paint, Gear Shift Assist Pro, Ride Modes Pro, Sport Suspension, High Handlebar, M Endurance Chain, Aluminum Engine Protection, Enduro Hand Protection, Off Road Tires),

- Or $1,495 for the Enduro Package Pro (Sport Suspension, High Handlebar, M Endurance Chain)

So, if you want the high-end suspension and access to the Enduro Pro Ride mode, but not the Trophy colorway, in theory you’d have to get the Premium Package and the Enduro Package and on top of that you’d have to buy all of the additional protection separately? But if you go with the Off-Road Package (designed specifically for the United States) you can't add in electronic cruise control or keyless entry? Sigh…

Even looking at what BMW's paperwork said for the MSRPs of the bikes we tested confuses me. Hence why I tried building my own on their site. They said that the Trophy I rode back to California had the Premium Package and the Enduro Package Pro and the Trophy paint along with Off-Road tires and the SOS emergency call feature. But it also had the hand guards and skid plate from the Off-Road Package… Something wasn't adding up. Through more digging (shout out to Oleg Satanovsky, BMW North America's very patient press contact) I found that in order to get electronic cruise control and keyless entry you have to combine the Premium and Enduro Pro Package together and add on the Trophy colorway. Also, the Trophy color seems to be the only way to add the beefier skid plate and metal hand guards. Confused yet?

As tested, the F 900 GS Trophy I left for Zack in our L.A. office has an MSRP of $18,360 (this includes $345 for BMW's built-in SOS system and $65 for off-road tires). When I built it out on BMW's website, I got $17,035, which included off-road tires but not BMW's SOS system. However, I couldn't add on keyless entry or electronic cruise control. TL;DR: If you want electronic cruise control and keyless entry (I could do without the latter) it's going to cost you nearly a $1,000 premium.

So at that price, it’s close to an equally equipped KTM 890 Adventure R and the Triumph Tiger 900 Rally Pro. I think the BMW is probably more enjoyable on the street than these bikes and somewhere in between the two off-road. It’s more affordable than the Ducati DesertX and arguably easier to ride off-road and nearly as much fun on the street. You could bring the Ténéré 700 and the Aprilia Tuareg into the conversion, but from a cost standpoint, I think it could be argued that those are two different buyers.

The conclusion

The F 900 GS came out swinging for the fences. It’s clear that BMW isn’t stoked on their dwindling market share in the middleweight segment. They arguably made the F 900 GS better in almost every way possible. Do I wish I had more control over the electronics and the ride modes? Yep. Should you probably pack a spare 21-inch tube and a Lexin pump in your tank bag? I would if I were you. Do I need a degree in quantum physics to figure out the pricing? It would help. Do I think it would be nice to get 200 miles out of a tank of gas? I guess. But did BMW strike a much better chord with this bike overall? I think so.

The engine is more powerful and more balanced across the entire rev range. The base suspension is worlds ahead of the previous version and is probably going to be more than enough for the average ADV rider, and if it’s not enough, you can upgrade to the performance version. The bike handles better, is lighter, and is more comfortable over all. This was the sweeping departure I had hoped for when I first saw the photos coming out of Europe.

If you too found yourself wondering if the reality of the machine could live up to the image? It does.

| 2024 BMW F 900 GS | |

|---|---|

| Price (MSRP) | $18,390 (As tested... I think...) |

| Engine | 895 cc, liquid-cooled, eight-valve, parallel twin |

|

Transmission, final drive |

Six-speed, O-ring chain or BMW's M-Endurance Chain |

| Claimed horsepower | 105 @ 8,500 rpm |

| Claimed torque | 68.6 foot-pounds @ 6,750 rpm |

| Frame | Trellis steel frame |

| Front suspension | Showa 43 mm fork, adjustable for preload and compression and rebound damping; 9.05 inches of travel |

| Rear suspension | Base shock, manually adjustable for preload and rebound damping; Sachs ZF Shock, manually adjustable for preload, high- and low-speed compression damping and rebound damping; 8.5 inches of travel |

| Front brake | Dual Brembo two-piston calipers, 305 mm discs with BMW ABS Pro |

| Rear brake | Single-piston floating caliper, 265 mm disc with BMW ABS Pro |

| Rake, trail | 28 degrees, 4.7 inches |

| Wheelbase | 62.6 inches |

| Seat height | 34.3 inches |

| Fuel capacity | 3.8 gallons |

| Tires | Metzeler Karoo 4, 90/90R21 front, 150/70R17 rear |

| Measured weight | 491 pounds |

| Available | Now |

| Warranty | 36 months or 36,000 miles |

| More info | bmwmotorcycles.com |