Years ago, I raced a Suzuki GSX-R600 with one cylinder disabled — a 450 cc Gixxer, dubbed the Cripple Triple. In retrospect, it was my first peek at the concept behind Kawasaki’s 2023 ZX-4RR.

The GSX-R450 was surprisingly good to ride, not because of its 70 horsepower, but rather the 40 additional horsepower that it didn’t make. Y’see, the 600-supersport-spec tires, brakes, and suspension were designed for 110 horsepower. Deactivating one cylinder meant that the whole chassis was suddenly under-stressed and, because of that, passed along a heap of confidence to the rider.

This new, 399 cc, four-cylinder ZX-4RR from Kawasaki is, in many ways, related to the Cripple Triple. In one way, by retaining the sophistication and luxury of high-end handling components while abandoning a chase for the most power. A sport bike enigma. And also, the Cripple Triple connects this new 400 cc sport bike with the class of yesteryear. But we'll come back to that.

Specs and tech

Plenty of people will have to be forgiven for mistaking the ZX4 for either its fraternal twin, the Ninja 400, or its big sibling, the ZX6-R. Call it generic Ninja if you like. Aside from the subtle lettering on the side, a few things set the ZX4 apart from the Ninja 400 — twin front-brake discs are the big giveaway, plus a lower windscreen and lower handlebars.

If Kawasaki had told me that the wheels, mirror assemblies, tail section, fuel tank, and a host of other little stuff was shared with a Ninja 400 I would have believed it. But actually, there aren’t any significant shared parts. Everything down to the steel-tube frame is a sort of bizarro, parallel-universe Ninja 400. The same, but different.

Of course the overriding difference is that practically every part on the ZX-4RR is a much higher spec. For example, ahem: A 4.3-inch full-color display, four ride modes, two power levels, adjustable traction control, an up/down quickshifter, radial-mount brake calipers, and much more sophisticated suspension than 300- or 400-class bikes typically use.

And then there’s the whole reason that the chassis is fancy in the first place: the ZX4’s 399 cc, inline-four engine. A quartet of 100 cc cylinders and 16 tiny valves. Beyond the undeniable cuteness of exhaust valves that are only three-quarters of an inch across, there are some nifty engineering efforts inside.

Machined combustion chambers, tender-loving care put into intake port smoothness and angle to promote extra flow through the cylinder, and varied intake-funnel lengths in the airbox are examples. None of the engine’s glitz is groundbreaking, but it’s fairly special in the context of this class of bike. The result is a rev ceiling of 16,000 rpm, and no need to put anything other than 87 octane in the tank.

On the track

My first taste of the ZX-4RR’s all-new everything was at Thunderhill Raceway’s East Course, a 2.9-mile strip of pavement draped over the softly rolling hills of Sacramento Valley, about an hour north of California’s capital. I puttered around the paddock before the first session started, in part to get a feel for the ZX4’s low-speed manners.

Foremost, the cockpit feels welcoming. Not as committed a riding position as a full-fledged sport bike but properly sporty at the same time. Wide, commanding clip-ons and a typical Kawasaki rider triangle — notably compact between the handlebars and the seat. For my six-foot, two-inch frame it meant I was fairly upright as long as my butt was forward on the seat.

Like a lot of bikes that rev north of 13,000 rpm, gearing feels short. Letting the bike idle in first gear shows 6 mph on the dash. In second gear, 8 mph. Throttle pickup is pretty smooth and the dash is status quo for a late-model Kawasaki — clean, clear data shown with a bar-type tachometer sweeping from left to right. Clutch pull is light (it uses the same slip-and-grip system as other Kawi sport bikes) and both of the hand levers are adjustable. Nice stuff, all of it.

Even just warming up and getting my bearings on the track, the ZX-4RR was clearly in its element. The engine seems happy to live above 10,000 rpm, wailing like a banshee but still nice ‘n smooth. Tipping from corner to corner the bike felt 20 or 30 pounds lighter than the spec sheet claims. I tried TC level 3 (wheel-speed informed, there is no IMU), which is the preprogrammed setting for Rain mode, and it was hugely conservative. Rightly so. Level 2 (Road mode) killed my buzz a lot less, then I moved on to TC level 1 which seemed totally adequate unless the weather is ugly.

Once I shook off my own rust and adjusted the tire pressure a bit (PSA: 43 psi is too many for the track) I rode as fast as I dared, looking for flaws in the ZX-4RR’s recipe. I never had any dramatic handling trouble, but as far as I can tell the shock was pretty overwhelmed with my 200-pound keister. It felt low in the rear, especially mid corner, despite adding spring preload.

I had a Kawasaki technician add spring preload in the fork, too, though there isn’t any damping adjustment so the tweaks were limited. Team Green says that the shock is largely the same as the one used on the ZX-10R flagship, albeit with a different spring rate and valving schedules. Ultimately, I stiffened the bike slightly, (plus played with compression and rebound damping to compensate), and still I never found the right balance. To do it again, I think I’d need more rear ride height, a stiffer spring, and a slightly taller seat. Some of that problem is on me, literally.

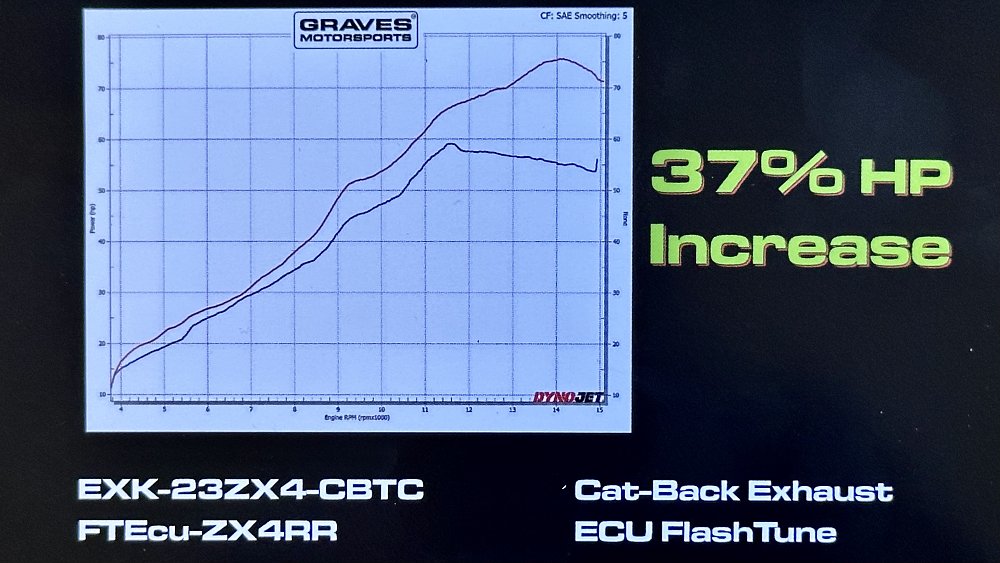

A bit of good news for my chonky self: good brakes. I like an ultra-sharp initial bite in my sport-bike brakes, and these binders don’t have that. Even so, there’s good power and feel, more than enough to slow down a bike that’s making less than 70 horsepower. Speaking of which, I’d be lying to you if I didn’t point out the most obvious and depressing drawback of the North American spec model, and that’s the unmistakable flat-spot in power above about 11,500 rpm. It’s a noise-emissions thing, we’re told.

The ZX-4’s engine is still hugely entertaining to hear at full song, but it’s hard not to wish for the lovely and linear power to keep on building instead of the bike holding its breath for the final 30% of the rev band. In other words, the experience is only slightly dulled. This thing is never going to be the fastest bike on the block, so maybe we don’t need to make a federal case of having 60 horses at the back tire instead of, say, 72? That’s not up to me, I guess.

What I can say for sure is that it’s a hoot to let the ZX4 howl all the way up to 16,000 rpm. In part it’s useful to have lots of over-rev capability on the track, and also because it makes my heart beat a little faster to hear the shriek of the engine at peak rpm. It’s awesome, and engaging, and at least a little bit special.

Whether or not the suspension suits your weight or the neutered power delivery ticks you off, the ZX-4RR walks a bit of a fine line for the track-day enthusiast. There’s more than enough quality in the features and componentry to keep an intermediate track rider happy, and it’s all a clear step above other bikes in this category. That said, it’s liable to be expert-level, or at least experienced, riders who want an engine that needs to be flogged lap after lap, right? Perhaps all of this is moot, because you want to know what it’s like as a street bike.

On the street

Any time I’m wearing race leathers during my initial impressions of a bike, I try to take those thoughts with a grain of salt. Something about being in a cowhide onesie with knee pucks seems to distort my idea of what’s comfortable. Happily, my first perception of the ZX4 as a street bike wasn’t far off.

Away from the track, it still felt pretty neutral for a sport bike, almost inviting. More than capable of a 140-mile ride around the hills and grasslands of Northern California, it turns out, and there were a few aspects that I liked quite a bit better at a relaxed pace. The quickshifter always felt good but a little strained on the track, just a little more effort than I wanted to use to click through gears. Mostly below 8,000 rpm on the street, and aside from the occasional lurch from first to second, it’s delightful. Buttery smooth, and a neat accompaniment to the gentle whir of the ZX4’s mill.

Between blissful swings through tree-lined corners and tickling the leaves with a tiny, screaming soundtrack, some things did bug me. The dash, for instance. I don’t like the long hold on the up or down buttons to switch ride modes. It feels distracting and a little clumsy, considering how good the design is otherwise. Also, why is it that when I’m in the adjustable Rider mode I can’t see my trip meter or engine temp? What have I done to deserve this?

The greatest user-experience mistake is that there’s an up/down rocker switch with a Lap button on the left handlebar, plus a Select button on the other side, and yet in order to navigate the main menu I had to stuff my hands between the triple clamp and the windscreen to use the two, rubber-coated buttons on the actual dash unit. You don’t need the menu on a daily basis, fine, but it’s undignified for a $10,000 motorcycle.

Especially one that otherwise feels so classy. It’s not just the sound or feeling of the engine that separates the ZX-4RR from other lightweight sport bikes. The thing is nice. Along with the smooth quickshifter and solid brakes, the seat is pretty plush and the slope of the clip-ons give the feeling of a true supersport. It feels so much less like a toy and much more like a purposeful, serious sport bike. Like good food or good alcohol, the flavor is bold without being harsh.

Odds ’n’ ends

This was my first chance to ride the ZX-4RR, but sometimes consumers have them before we, the press, get our butts in the saddle. An old friend of mine bought one and has been riding it around for a month or so now, so I thought I’d include some of his notes.

He referred to the ECU limitations for the North American model as “a crime against consumers, the bike's engineering team, and reason itself.” He admits that he still loves the bike, he just thinks it’s annoying that every owner has to flash the ECU and void their warranty if they want to feel the true character of the engine. I’d say that’s pretty fair.

Also of note, the punishing price of insuring a Ninja. He also owns a Ducati Hyperstrada 821 and a Husqvarna 701 Supermoto, and he reported that insuring the ZX-4RR alone costs “notably more” than the combined price of the Ducati and the Husky. Unrelated to that, he asked why the livery looks so generic. Why not mimic that glorious, green/blue/white paint of an early ‘90s ZX-7, like Kawasaki’s own World Superbike team did a couple of years ago?

Or, for that matter, paint it like a ‘90s ZXR400. Which actually brings me back around to the other major connection to the Cripple Triple, spiritual sibling to this ZX-4RR. More intriguing than the sweetness of the strange recipe is the origin story.

As some readers might remember, the early 1990s saw a glut of 400 cc supersport motorcycles, bikes like Yamaha’s FZR400, Honda’s VFR400, and Kawi’s own ZXR400. Access to these models varied depending on where in the world you lived, but even in the largely restricted US of A, racing classes cropped up for this class of machine, populated with FZR400s and sprinkled with gray-market VFR400s.

A couple of decades after their heyday, as parts started drying up and enthusiasm waned, the idea of crippling a GSX-R600 for the sake of reinvigorating a racing class got people excited. The concept — a purebred, screaming supersport with 25% less power — and its potential value, was alive in people’s minds.

And that is a crucial mental step to take. The value that a ZX-4RR brings to a rider doesn’t fit very well into a conventional framework. If you want the most horsepower for the least amount of money, this isn’t the bike. If you like the idea of paying a little more for a ZX-6R, or building a Ninja 400 track bike with the $4,000 you’d save, absolutely do that.

The ZX-4RR’s annoying dash buttons, lack of damping adjustability in the fork, and hamstrung power are imperfections, plain and simple. But sport bikes are always imperfect, and I can’t bring myself to dislike the ZX-4 for those reasons. It is a well executed version of what it’s supposed to be — the most refined and exciting small sport bike you can buy today.

| 2023 Kawasaki ZX-4RR | |

|---|---|

| Price (MSRP) | $9,699 |

| Engine | 399 cc, liquid-cooled, 16-valve, inline-four |

|

Transmission, final drive |

Six-speed, chain |

| Claimed horsepower | na |

| Claimed torque | na |

| Frame | Steel-tube trellis |

| Front suspension | Showa SFF-BP 37 mm fork, adjustable for spring preload; 4.7 inches of travel |

| Rear suspension | Showa BFRC Lite shock, adjustable for spring preload, compression and rebound damping; 4.9 inches of travel |

| Front brake | Nissin four-piston calipers, 290 mm discs with ABS |

| Rear brake | Nissin single-piston caliper, 220 mm disc with ABS |

| Rake, trail | 23.5 degrees, 3.8 inches |

| Wheelbase | 54.3 inches |

| Seat height | 31.5 inches |

| Fuel capacity | 4.0 gallons |

| Tires | Dunlop Sportmax GPR300; 120/70ZR-17 front, 160/60ZR-17 rear |

| Measured weight | 420 pounds |

| Available | Now |

| Warranty | 12 months |

| More info | kawasaki.com |