I guess I’ll never truly know what it’s like to ride a motorcycle 100 years ago, because I can’t go there. But, even if I don’t have a machine to take me back in time, I was able to find the next best thing — a Harley-Davidson Model J, circa 1924.

Then again, you don’t just “go.” Getting up to speed on a motorbike from 1924 is a layered process, and pretty foreign for an average enthusiast. A quick walk-around tells you that the Harley J is not going to be like most motorcycles. A clutch pedal on the left floorboard and a hand shifter, plus two rear brake pedals and, uhhh, does the left grip twist, too? What’n the heck is that about?

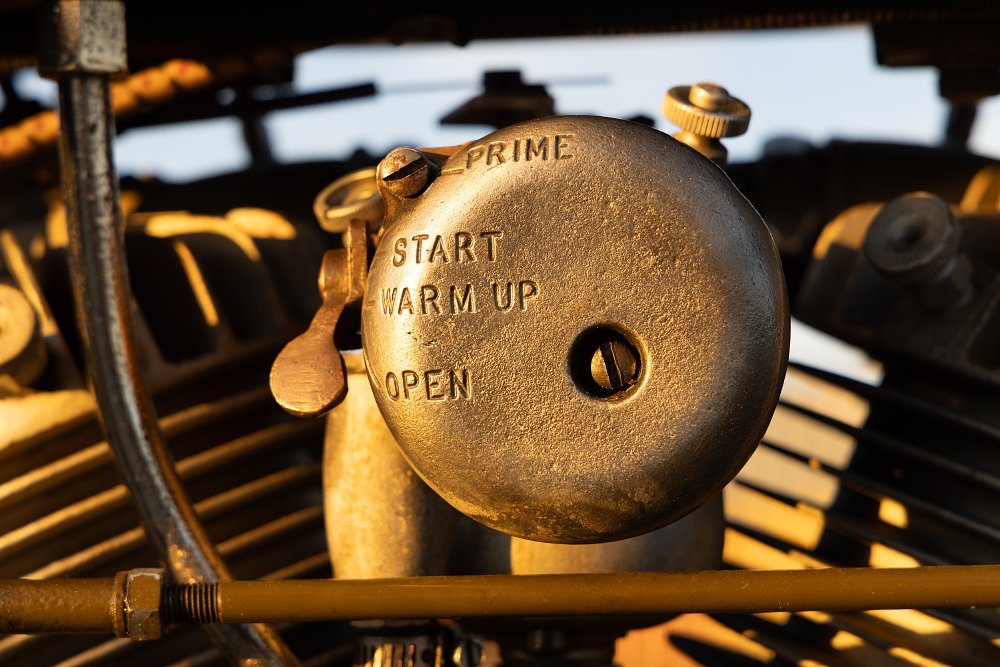

Starting the Model J is emblematic of how complex the machine is compared to any motorcycle from the past 50 years. I followed the owner’s instructions as best I could remember. Flick the petcock on and pull the choke, sure, I remember that from my dirt bike as a kid. But, which of the four settings on the carburetor do I use? They’re labelled, luckily, with deep lettering engraved into the outward-facing plate. For this particular J, only three were needed.

I pulled the primitive little lever up to Prime (and watched the top of the needle get yanked up out of the housing), then opened the throttle all the way, but left the ignition off, and gave the starter pedal two nice, smooth kicks. Then, closed the throttle and pushed the choke lever back down to Warm Up.

There’s no clutch lever on the handlebar, but that left twist grip is important — I rolled my wrist forward on the grip (like closing a left-side throttle) to retard the ignition fully. That sets the spark plugs to ignite after top dead center, which keeps the engine from firing back against the kick starter and threatening your lower leg. Now, finally, the ignition could be switched on.

With the springless throttle cracked slightly, one more gentle but firm kick and the Model J jumped to life. The last part of the start-up procedure was to roll the ignition timing to fully advanced, now that it was up and running, and the engine responded by clearing its throat and settling into a lumpy, clattery idle. Never has a well-tuned bike been such a challenge, or been so rewarding, to get started.

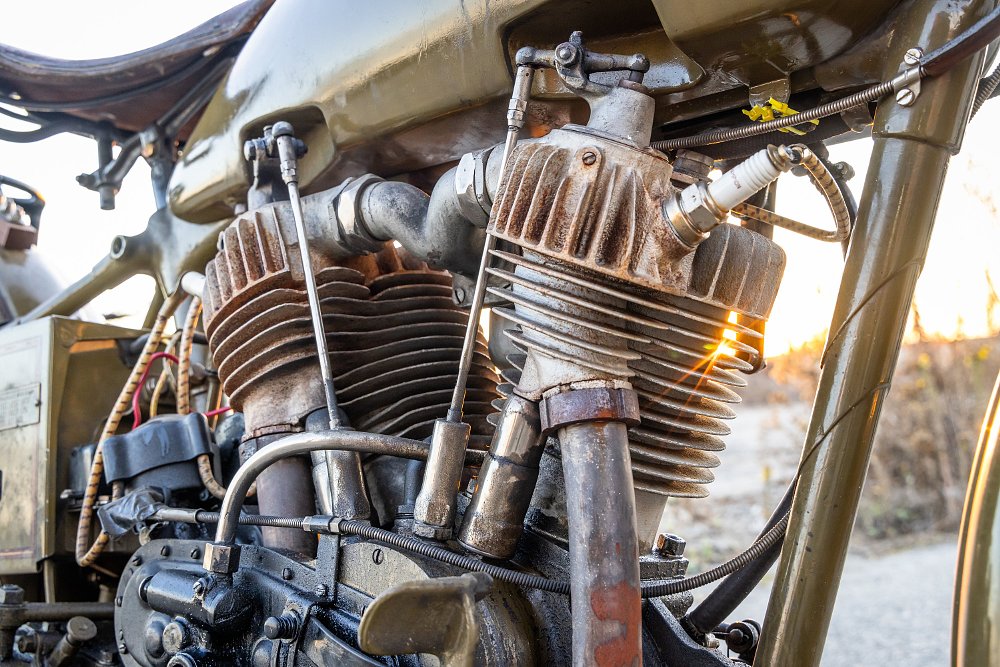

Part of that joy is seeing the machine come to life. At first approach the Harley J looks, feels, and smells like a piece of farm equipment. There’s grime clinging to the olive-green finish, wires in fabric sheaths, and seemingly skeletal parts of the engine poking out every which way. Most fascinating of all is the valvetrain, which is an intake-over-exhaust or “pocket-valve” setup — the exhaust side rides next to the cylinder like a typical side-valve head but the intake pushrod and rocker arm reach up above the head to face the valve down into the top of the cylinder head.

It looks like an oil painting or a wax statue that belongs in a museum, but when it fires up a whole new world is exposed. The cables and wires jump and vibrate with life, levers and pedals rattle. The intake pushrods and rockers click methodically up and down while the exhaust puffs smoke like an old cartoon. It’s just plain delightful.

Riding the J was even more complicated and nerve-wracking than getting it started, and also a puzzle all to itself. This Model J I tested is a veteran of the Motorcycle Cannonball and so has a retrofitted front brake for added safety on public roads. Originally, the J was rear-brake only, activated with a right-side foot pedal like most bikes. I was keen to try to ride it without relying on the front brake, while being honest with myself that there was plenty of other stuff to worry about.

The clutch is a rocker pedal on the left side, pivoting near the arch of your foot, described as a “toe-to-go” because pressing down with your heel spreads the plates and rocking forward engages them to make the bike go. If you’re not familiar with tank-shift motorbikes, you might be thinking this setup would create a few problems and, yes, I can confirm it does.

I figured my fluency with manual-transmission cars would do me some good with a foot clutch, but it being a backward motion from a typical car was a curveball. Once I got the hang of the motion with my ankle, it started to feel natural. Still, it’s been decades since I had to think so hard about using a clutch.

Once I was rolling, the next issue reared its head, which is a pretty simple one: If my left foot was in charge of clutch engagement and my right foot was in charge of braking, I needed a whole new strategy for balancing the bike when I came to a stop. I had to either get in the habit of throwing the transmission into neutral when I was slowing down, which was the suggestion of the bike’s owner, or be pretty damned confident that I was stopped before taking my right foot off the floorboard.

I chose a combination of those two tactics, and it worked surprisingly well. That’s mostly due to the J being fairly calm and stable. It weighs about 445 pounds, has a low seat, and is quite narrow. All very reasonable. It also makes a little less than 10 horsepower and has a 61-inch wheelbase, so it’s not exactly a wheelie monster.

Coordinating all of the usual tasks in a mixed-up pattern was tricky, but eventually made sense and I was able to relax for brief periods between traffic and stop lights. In these moments, it was hard not to reflect on this surreal encounter, a 100-year old motorcycle meeting the streets of a modern-day city.

It’s hilariously basic, but amazingly smooth considering the only rear suspension is an undamped spring in the seat post. The front suspenders aren’t much better, and yet the J bounces along happily and even swings through curves with plenty of stability. I also just loved the exercise of shifting through the three-speed gearbox and trying my best, sometimes failing, to be sympathetic to the bike’s age.

As the J chugged along the wide, concrete surface streets of Los Angeles I thought about what this machine, and ones like it, offered the world way back when. A military courier during World War I, blasting across some shredded section of Europe with important news from who-knows-where, about who-knows-what. A mailman in rural Wisconsin, bashing down a road with a sidecar attached, using these two reliable cylinders to earn a living.

Aside from delivering tangible things, the Harley J, along with all of its many siblings and competitors, must have brought such an intense feeling of freedom. The idea that you could simply saddle up and take off in practically whatever direction you pleased, at 50-or-so mph, would have been intoxicating. No wonder people challenged themselves by riding across continents or up mountains. It could have easily felt like nothing was out of reach.

And, of course, with the impact of Harley-Davidson on American culture and motorcycling history as context, this bike feels special. Historians and hooligans alike will argue over how much of the Motor Company’s success is deserved, but there’s no questioning it has grown into a behemoth just like there’s no question this bike is related to late-model Harleys. That rhythmic clap from the exhaust is still echoing a century later.

Time travel is a fascination of the human mind. It’s easy to imagine what it might be like to experience a war of the past or a paradise of the future, and yet it’s impossible to actually move back or forward in time. Remnants of history, like the Harley J, give us little tastes of what the world used to be. As we plod along through the present we can take the time to look at these treasures, close our eyes, and envision the people, the weather, the smells, and the feeling of being alive and breathing the air of a different era.